Antoinette Portis is the subject of this month’s author interview, and I have to confess–I’ve been looking forward to this one for some time. Anyone who can get away with using words like “Froodle” and “Frints” in picture book titles is awesome. Obviously.

Antoinette Portis is the subject of this month’s author interview, and I have to confess–I’ve been looking forward to this one for some time. Anyone who can get away with using words like “Froodle” and “Frints” in picture book titles is awesome. Obviously.

We cover her bio pretty well in the Q&A below, so let’s close out this intro by sharing two of her books that I totally dig. Go (re)read them now. Seriously.

Website: www.antoinetteportis.com

Facebook: www.facebook.com/antoinette.portis

Twitter: @portisa

Instagram: www.instagram.com/bathingonthemoon

Goodreads: www.goodreads.com/author/show/129061.Antoinette_Portis

RVC: When did your interest in writing first show up?

AP: When I was in sixth grade, my best friend and I vowed that we were going to each write and illustrate a book. It took her 5 years before she presented me with one that she’d written in pencil on lined paper.

It took me much, much longer to hold up my end of the deal. 30 years!

RVC: Along the way, you went to art school, too.

AP: Right. I was terrified of writing after a freshman poetry class, so I veered toward visual art instead and got a BFA at the UCLA School of Fine Arts. I was also a video performance artist, but guess what? There’s wasn’t a career in that waiting for me. I started working in the commercial realm as a graphic designer so I could make a living and still be creative. Over the years, I was an advertising art director, making print advertising and TV commercials.

Then I had a baby and did a lot of freelance work in advertising.

RVC: And you found your way into working for Disney.

AP: I got a 3‑day gig at Disney working for a creative director I’d known from my advertising days. She was head of Creative Resources at Disney Consumer Products. I ended up staying there for almost nine years. It was super fascinating to be there, to be part of this huge American cultural thing–not all of which I agreed with.

I loved the creative challenges. My team did so much good work that at the end of each day, my mouth would hurt from smiling.

In advertising, “cool” was what you wanted, but at Disney, “cute” was a major vocabulary word. I got completely indoctrinated into cuteness, into the world of child-friendly creative.

RVC: Why did you make the shift from that amazing job to the world of kidlit?

AP: I still had this secret part of me locked away in a treasure box–the artist who wanted to make her own stuff.

As I moved up the corporate ladder, pretty soon I wasn’t working directly with my creative team any longer. Most of my job was sitting in meetings with pages of tiny numbers on the table in front of me. I’d be in business meetings all day, return to my desk at 6pm to catch up on my work, then finally leave around 7:30pm, or later. I wasn’t thinking much about color and design anymore, but about deals and Target sales numbers. I was like, “What am I doing here? My soul is dying.” I wanted to see more of my kid and get back to being a creative person again.

Disney is an intellectual content provider, but I wanted to make my own IP.

I decided to leave. We’d had a bunch of layoffs, and it came to the point where they paid people to leave voluntarily. It was a perfect opening. I felt like a bird in a cage and the door creaked open for me. I could fly.

I think of that time as me being birthed out of the corporate world to what I was really supposed to do with my life.

So now I was home and could think about what kind of stuff I wanted to make. I considered going back to making site-specific sculptural installations–something I’d done in art school. Or should I make children’s books, which was something I knew I’d wanted to do since elementary school? I weighed which arena would be more welcoming to a middle-aged woman and that helped me decide on picture books.

Well before Disney, I took a class at Otis College where I wrote a picture book manuscript that I’m just now getting around to illustrating. Full circle.

RVC: Were you writing the whole time?

AP: Not while I was at Disney. There was group of us at Disney–me, a poet, a painter, a knitter, etc.–who kind of met up and encouraged each other not to drop our dreams, but honestly, with Disney, everybody’s too busy to do anything else.

After Disney, I took children’s book classes at UCLA extension and Art Center College of Design (Marla Frazee’s class). I went to SCBWI conferences so I could understand how the publishing business worked.

I wrote a couple of manuscripts that I thought were okay. I’d paginated them and made them into little dummies. I started to get a sense of the rhythm of a 32-page story, how it unfolds, how the whole thing works as a unit.

RVC: How did it go from there?

AP: The first book I submitted was promptly rejected. I revised and sent it out again, and it got rejected again.

Then I learned that Barbara Bottner–a writing teacher I had in 1993 before I started at Disney–was moving back to the area and starting up a guided critique group, so my current writing group just migrated over to hers.

I showed her the manuscript that got rejected. I was proud it. It was a smart idea. Cute. Clever.

Barbara looked at it, tossed it on the table, and said, “No, you’ve got to write something that matters to you.” Her theory is that we each have a specific age that we connect with as a writer. She wanted me to go back to my childhood and mine it for something that really mattered to me.

I had ideas. (I have lots of ideas–I keep lots of lists.)

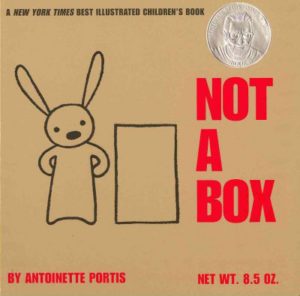

One idea was based on my memory of playing in cardboard boxes. I remembered how much fun it was as a kid to do that–to entertain ourselves with our own imaginations. I first pictured the book as line drawings of a kid sitting in a box,  with transparent overlays to show what they were imagining. But that wouldn’t work–you’d see the overlay before the box. The imagination part needed to come second. So the reveal had to follow a page turn. Which turned me on to the power of a page turn in a picture book. You really feel that power when you read out loud to kids–they shout out what’s on the next page before you’re turned. It becomes a guessing game or a chance to show off their knowledge.

with transparent overlays to show what they were imagining. But that wouldn’t work–you’d see the overlay before the box. The imagination part needed to come second. So the reveal had to follow a page turn. Which turned me on to the power of a page turn in a picture book. You really feel that power when you read out loud to kids–they shout out what’s on the next page before you’re turned. It becomes a guessing game or a chance to show off their knowledge.

Once I saw what format would work, the text came easily–72 words just popped out. It was one of the really lucky times where the whole thing came together fast without a lot of pain and agony.

It’d be great if every idea unfolded like that. But no.

RVC: What lessons from those business world experiences proved most helpful in creating your own picture books?

AP: You have to grow a thick skin. You have to know that more than one idea will come to you.

In the advertising world, you pull an all-nighter coming up with creative based on a strategy the account guys have given you. You come up with something brilliant and pin it up in the conference room, then the business guys come in and announce that they’ve changed strategies. Here’s the new one. So now go be brilliant again.

You might want to cry, but you go at it again. In advertising, creatives are thought of as an idea factory. You HAVE to be that–that’s your job.

I’ve seen in many picture book classes how there can be a preciousness–this is MY ONE idea. Like you’re never going to have another good one, so you cling to it and nurse it for years and years, even if it’s not working, or it’s not going to make it in the marketplace.

You’ve got to be able to let go when an idea isn’t working, or when you’ve beaten the life out of it. There’s not just one idea that’s doled out to a person in their life. There’s an endless supply of ideas!

And it helps to be strategic in the sense of how a book has a theme, an idea you’re trying to convey. You can’t have 17 themes crammed into a 32-page picture book. The main idea–whatever it is–has to be set up in the beginning and then paid off at the end, hopefully in some surprising and satisfying way.

RVC: In a recent interview, you said, “Imagination is a super power all children possess–and it’s one they can exercise freely. I can’t stop wanting to celebrate that!” How does this impulse play into the creation of your own picture books?

AP: Imagination is a big theme for me in my work–it keeps showing up. But I don’t want to tell children “Use your imagination!” I want to show and reflect back to children how they do use their imaginations. I want to do it on their terms–not through the understanding of an adult.

Kids don’t run around saying, “I’m going to imagine now!” They just play. They make stuff up. The line between reality and imagination is blurred for a kid. It’s seamless how they move from one to the other.

RVC: Since we’re talking about the element of play, let’s talk about your illustration. It seems that you like to change up your art style from book to book. How do you know when you’ve got the right match for the current project?

AP: I spent my entire corporate career being an art director. My job was to have an idea, then hire someone else to bring that idea to life. Before the internet, we had these thick reference books with the portfolios of all these amazing illustrators. You’d leaf through it, page after page, to find the artist or photographer with the exact right style for the job. Now I write a manuscript and think, argh, I can only hire myself! Where’s my big fat book of art styles to pick from?

The manuscript I’m illustrating now, I wouldn’t (and couldn’t) have tackled 20 years ago. Finding my voice as an illustrator is an ongoing process. Getting away from drawing with a thick black outline opened up new terrain for me. I’m working looser, letting accident and spontaneity be more a part of the final result. I now spend a lot of time experimenting with different materials and tools. I’m loving sumi ink and big funky brushes these days. I’m making leaf prints, cutting stamps out of erasers, and there are clouds of vine charcoal dust settling on my drawing table. I’m following my intuition more–being open to more inspiration. So now I’m finally ready to illustrate the first picture book manuscript I ever wrote.

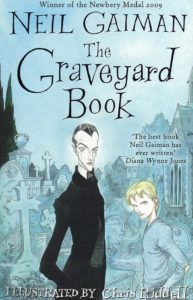

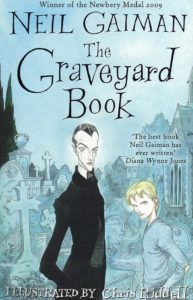

The process of growing reminds me of something Neil Gaiman said. He’d had the idea for The Graveyard Book decades before he wrote it, but he didn’t feel like he could do the idea justice so he let it  sit until he was ready. And one day he was. (And it’s an amazing book!)

sit until he was ready. And one day he was. (And it’s an amazing book!)

I have ideas that I never see myself illustrating because they require a style outside what I do. I’m never going to be, for example, an oil painter.

Some people are masters of a specific style. They might only work with a certain pen, or a particular paint set. They’ve perfected their craft over years and they’ve mastered it. That’s a wonderful thing. But it’s not how I work. I get a real charge out of not knowing exactly how I’m going to illustrate a book beforehand. I might do 6 different art styles and then talk with my editor about which one works best.

Apparently, I like to be mildly terrified at the beginning of a project.

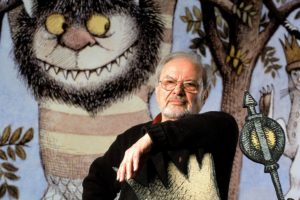

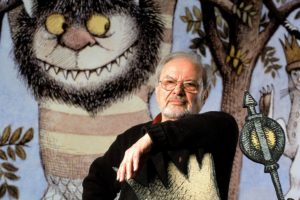

RVC: You were lucky enough to be a Sendak fellow in 2010 (which seems mildly terrifying to me since he’s intimidatingly terrific!). What was the real takeaway from that experience?

AP: The real takeaway for me was the appreciation for what an amazing human Maurice was. Having him as a friend was a beautiful, beautiful thing. And having him believe in my work was awesome.

Plus there’s the friends I made there. Rowboat Watkins was a fellow Fellow, and we’re still friends. We share work back and forth, and we can count on each other to be honest and thoughtful.

I remember Maurice being so disheartened by how commercial the world had become, and how so many publishers were more concerned with enhancing stockholder value (e.g. making a profit) than in bringing great work to the marketplace. So he told us that we’ve got to be spies, to sneak depth and meaning into our work so the corporate overloads don’t even notice it’s there.

I remember Maurice being so disheartened by how commercial the world had become, and how so many publishers were more concerned with enhancing stockholder value (e.g. making a profit) than in bringing great work to the marketplace. So he told us that we’ve got to be spies, to sneak depth and meaning into our work so the corporate overloads don’t even notice it’s there.

Maurice made the point in many interviews that just because picture books are for children, that doesn’t mean they are devoid of psychological truth. He certainly proved that in his work–Where the Wild Things Are is still the gold standard for what a picture book can accomplish. He didn’t condescend to children, or patronize them. He recognized them as fellow human beings. Picture books can deal with the deepest, most profound ideas. And like great novels, they do it obliquely, not by hitting you over the head with their philosophy.

For example, there’s Jon Agee’s wonderful The Wall in the Middle of the Book.  You could write a dissertation about that book. But if you told someone sitting next to you at a dinner party that you’d read this great book and then told them it’s a picture book, they’d laugh in your face. But the Agee book is funny, engaging, and profound. It’s a perfect creation. And so on point for our times.

You could write a dissertation about that book. But if you told someone sitting next to you at a dinner party that you’d read this great book and then told them it’s a picture book, they’d laugh in your face. But the Agee book is funny, engaging, and profound. It’s a perfect creation. And so on point for our times.

A good picture book IS a spy. It’s sneaking meaning into your life without you noticing.

RVC: I’m a fan of that Agee book too–it’s one of the OPB 18 Favorites of 2018. But let’s circle back to something we’ve touched on before: writing groups. What role does a writing group play in your process?

AP: I’ve heard people say, “I’ve read my book to my kindergartner and he loves it!” as if that guaranteed a book’s success.

No. You’ve got to get through the gatekeepers (agents and editors and acquisition committees) who are both savvy and jaded. Editors see zillions of manuscripts, so you’ve got to hone your writing and submit something that already works. They’re not going to fix it for you. Their job isn’t to mine raw ore. You have to hand them a gem and they will polish it. That means you have to put your text through the filter of other people’s eyes to make sure it’s working the way you meant it to.

Sometimes I find myself defending my work in my critique group because I know what I was trying to say, and to me, I said it. But they’re not getting it. So I listen and the pushback helps me clarify my aim, so I can set about communicating better. A crit group lets you know if you’ve actually communicated.

There’s a whole complex dynamic as a book unfolds in the space of a crit group. Sometimes there are wrong turns. There’s a rhythm to the process that took me years to internalize. The most important thing is that you can’t take a crit of your writing personally–it’s about elevating the work.

But yes, sometimes the feedback is painful. Sometimes you just gotta cry on the drive home. Then you get back to work and rewrite that sucker.

I’m still in a critique group. I can’t go all year, though, since I spend a part of it illustrating and that requires total immersion. I need to be completely focused for that. It’s the other side of the brain and once I’m hanging out there, it’s all about pictures.

Anyone who is serious about making picture books should join a crit group with people whose ideas and talent you respect. (Patiently building mutual trust is required.)

In my class at UCLA, a group of us decided, “Hey, we’re helping each other, so let’s form a critique group together.” That’s what I was hoping would happen as I took each writing class, and finally a group of us clicked. And some of us have been together for a long time now, maybe 15 years.

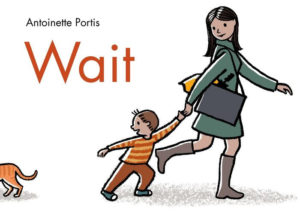

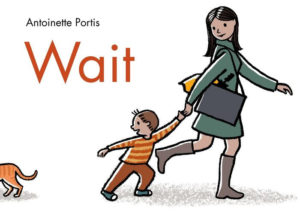

RVC: Wait feels like a special book for you. In what way is your relationship with that book different than you have with others?

AP: There are two special things about Wait–one is formal, the other is the heart and soul part.

With Not a Box, there’s a push and pull between adult and kid. It’s about a child’s imagination, but also about a child defending it against the disbelief and casual cynicism of adults or some other bystander who’s not into playing along with them.

Back to that memory of my brother and I sitting in a cardboard box in our driveway, playing train. I can picture my mom washing dishes, looking out at the window at us, thinking, “They’re going to leave those boxes out there and I won’t be able to get the car into the garage …” You know–the practical stuff adults think.

Another time, we used every single sheet, blanket, and towel in the house to build a fort. When she asked us to clean it up, we were like, “No, it’s fantastic. Leave it up forever!” (She might have cried. But then she sicced Dad on us and we had to take it down and do a lot refolding. A lot.)

I’m interested in that kind of dichotomy between the child’s world and the adult world, which is so much a part of growing up. Kids are constantly getting into trouble and breaking the boundaries set for them, often accidentally.

The idea for Wait came when I was sitting in a café and a mom walked by with a boy  (about 2 years old) who broke free and ran over to look at a bug on the windowsill right in front of me. He was rapt.

(about 2 years old) who broke free and ran over to look at a bug on the windowsill right in front of me. He was rapt.

She grabbed his hand and dragged him down the street.

Hello, picture book!

That happens a billion times a day, where an adult’s agenda overrides a child’s agenda. Kids learn about the world by looking at things that adults have already learned to take for granted or are too busy to stop and see. Kids are fascinated by the ants in a crack in the sidewalk and random seed pods. Adults stomp right on past them.

This tug of war is a poignant situation, and I’m on the kids’ side. That’s the emotional underpinning of Wait.

One version of the book had variations of what the mom says, like “Let’s keep moving, buddy,” etc. I thought the book need that to be interesting. But then I realized that the narrative unfolds in the pictures–that’s where the interest lies. So a super-tight, terse structure worked perfectly. The dialogue is just a simple back and forth. The mom says “Hurry” and all the child says is “Wait.” Until the end, that is, when the mom capitulates and things switch. That change becomes a big, big moment.

To figure out this book, I felt like I had to put everything I’d ever learned about picture books into it. In the pictures, there’s foreshadowing, repeated motifs, and visual jokes. But the real challenge was to create a visual narrative, not relying on poetic text, that had an emotional payoff. I wanted to let readers figure out what the theme is. It’s clear and it’s there, but not actually spoken. I never want to speak a theme.

RVC: That sounds like a truth from the business world, too.

AP: The same thing is indeed true in advertising. With an ad campaign, there’s always the underlying strategy. You had to think of a tagline to support it, but you couldn’t use the strategy as the tagline.

A strategy might be “Our cars are better” or “Drive our cars and everyone will think you’re cool.”

But you had to find a clever, funny, or powerful way of communicating that concept, so people would be emotionally or intellectually engaged with it.

RVC: Beyond the obvious–finish the work, proofread, send it out, etc.–what’s the best practical tip you have for aspiring picture book writers?

AP: The main thing is to be open to criticism. Be more committed to making the work better than to sticking with the germ of an idea as it originally came to you.

A novelist (I can’t remember where I heard this) once said that whatever initial idea you had for a book–whatever that one thing was that spurred you to spend years writing it–might need to be discarded as the idea takes on its own life and evolves into what it needs to be, its final form.

In a picture book, sometimes your favorite sentence has to go–the one that’s the most beautiful thing you’ve ever written. The book around it has gone to a new place, so bye bye beautiful sentence. (Maybe you’ll find a new home someday.)

I once heard Jon Klassen say that you have to be true to the idea. It’s all about the idea, not about you or your self expression. Once the idea is in existence, it tells you the rules if you just listen. It tells you what it needs.

RVC: Is this ever a challenge for you?

AP: Sometimes there’s a wrestling match. The book says, “You know I’m not going to work if you hang onto that thing you’re hanging onto,” but I dig in my heels. It might take me a while to face up to the fact that something I really like needs to go.

Manifesting an idea requires rigor and sometimes an idea has to whup you upside the head to get your to listen.

RVC: Alrighty–it’s time for the SPEED ROUND! Quick questions. Even quicker answers. GO! Guiltiest TV binge-watching pleasure?

AP: It’s a show on Acorn (Australian TV) called “800 Words,” about a columnist whose  wife died so he moved from Australia to this funky town in New Zealand with two teen kids and he writes a column for a dinky local newspaper. My husband and I are both addicted. He says, “Let’s see what George is up to,” which is ironic because George is never up to much and that’s what’s so great about the show.

wife died so he moved from Australia to this funky town in New Zealand with two teen kids and he writes a column for a dinky local newspaper. My husband and I are both addicted. He says, “Let’s see what George is up to,” which is ironic because George is never up to much and that’s what’s so great about the show.

Continuous mellowosity.

RVC: Favorite literary villain?

AP: The Grinch, but from the book, not the modern movie versions. I think the green guy is on my mind because Christmas kind of wore me out. Sometimes I wanted to pack it up in a sack and stuff it in the back of a cave myself.

RVC: If you weren’t in the kidlit biz but you still left your job at Disney, you’d now be a ______?

AP: I’d freelance in graphic design to make a living and then be writing and making art on the side. Maybe there’d be cardboard sculptures all over my walls.

RVC: Best dinner foursome made up of picture book characters?

AP: I’d like to have dinner with Winnie the Pooh, Owl, Piglet, and Eeyore. I feel like I’d have a great time with them.

We had those books when I was a kid, but I didn’t really read through them all until high school. I remember finishing them late one night and sobbing because I couldn’t go to the Hundred Acre Wood. I fervently hoped, when I died, that’s what heaven would be like. But now, writing for kids, reading and drawing with them, my life is its own Hundred Acre Wood.

RVC: Funniest picture book you’ve recently read?

AP: My friend Rowboat Watkins wrote a book Rude Cakes that has has one of the funniest page turn reveals ever.

AP: My friend Rowboat Watkins wrote a book Rude Cakes that has has one of the funniest page turn reveals ever.

RVC: Three words that sum up what a great picture is/does.

AP: Says something true about being a human being.

I’m going past three words here, but it’s important–a picture book isn’t didactic but rather something that tick-tick-ticks in the back of your mind like a time-release capsule. It unfolds in your thought and moves you in some way. It makes you feel connected to your own humanity, and maybe makes you able to see your own behavior in a way that resonates for you. And maybe even changes you a tiny bit.

RVC: Thank IS worth going past the three word limit. Thanks so much, Antoinette!

The first Industry Insider interview of 2019 is with Emily Feinberg, who got on my radar because her name kept appearing in the Dealmakers section of Publisher’s Marketplace. But what REALLY sealed the deal for me in terms of making her a priority must-have for a 2019 Industry Insider interview? Her terrific Twitter bio that simply confirms what I already suspected–we’re kindred spirits. Like literary peas in a bookish pod. Like two ducks in an inky ocean of words. Like two psychic penguins who … well, you’ll see for yourself.

The first Industry Insider interview of 2019 is with Emily Feinberg, who got on my radar because her name kept appearing in the Dealmakers section of Publisher’s Marketplace. But what REALLY sealed the deal for me in terms of making her a priority must-have for a 2019 Industry Insider interview? Her terrific Twitter bio that simply confirms what I already suspected–we’re kindred spirits. Like literary peas in a bookish pod. Like two ducks in an inky ocean of words. Like two psychic penguins who … well, you’ll see for yourself.

EF: It’s so hard to choose. Two books coming out around the time of this interview that I’m SO proud of are Just Right: Searching for the Goldilocks Planet, a gorgeously written and illustrated nonfiction picture book about exoplanets, and How to Walk An Ant, about a girl who shows the reader how to leash up and walk ants–both out this winter!

EF: It’s so hard to choose. Two books coming out around the time of this interview that I’m SO proud of are Just Right: Searching for the Goldilocks Planet, a gorgeously written and illustrated nonfiction picture book about exoplanets, and How to Walk An Ant, about a girl who shows the reader how to leash up and walk ants–both out this winter!

Antoinette Portis is the subject of this month’s author interview, and I have to confess–I’ve been looking forward to this one for some time. Anyone who can get away with using words like “Froodle” and “Frints” in picture book titles is awesome. Obviously.

Antoinette Portis is the subject of this month’s author interview, and I have to confess–I’ve been looking forward to this one for some time. Anyone who can get away with using words like “Froodle” and “Frints” in picture book titles is awesome. Obviously.

sit until he was ready. And one day he was. (And it’s an amazing book!)

sit until he was ready. And one day he was. (And it’s an amazing book!) I remember Maurice being so disheartened by how commercial the world had become, and how so many publishers were more concerned with enhancing stockholder value (e.g. making a profit) than in bringing great work to the marketplace. So he told us that we’ve got to be spies, to sneak depth and meaning into our work so the corporate overloads don’t even notice it’s there.

I remember Maurice being so disheartened by how commercial the world had become, and how so many publishers were more concerned with enhancing stockholder value (e.g. making a profit) than in bringing great work to the marketplace. So he told us that we’ve got to be spies, to sneak depth and meaning into our work so the corporate overloads don’t even notice it’s there.

wife died so he moved from Australia to this funky town in New Zealand with two teen kids and he writes a column for a dinky local newspaper. My husband and I are both addicted. He says, “Let’s see what George is up to,” which is ironic because George is never up to much and that’s what’s so great about the show.

wife died so he moved from Australia to this funky town in New Zealand with two teen kids and he writes a column for a dinky local newspaper. My husband and I are both addicted. He says, “Let’s see what George is up to,” which is ironic because George is never up to much and that’s what’s so great about the show.

David C. Gardner is an award-winning illustrator and visual development artist. A former artist for Walt Disney Animation Studios, he has illustrated numerous picture books, including his latest from Sleeping Bear Press, Write On, Irving Berlin! by Leslie Kimmelman (

David C. Gardner is an award-winning illustrator and visual development artist. A former artist for Walt Disney Animation Studios, he has illustrated numerous picture books, including his latest from Sleeping Bear Press, Write On, Irving Berlin! by Leslie Kimmelman (