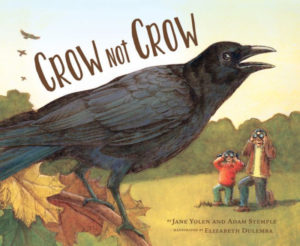

As part of a whirlwind blog tour to support their new co-authored picture book, Jane Yolen and Adam Stemple share thoughts about the genesis and writing of Crow Not Crow.

(OPB doesn’t do many non-Monday posts, but when we do a Bonus Goody, it’s always going to be worthwhile like this. Enjoy!)

JY: I remember the first time you talked about teaching your wife Betsy how to bird using something you called “Crow Not Crow.” She was a Minneapolis girl and really didn’t know one bird from another. But you had been taught to bird as a child by your father who had grown up in the mountains of West Virginia. I thought Crow Not Crow might make a great title for a picture book, but since it wasn’t my idea, I left it alone. Only much later did I start bugging you about it.

AS: The actual teaching idea started out as a joke, splitting all of the bird kingdom into two classes: Crow and Not Crow. But the more Betsy and I joked about it, the more useful it started to seem. She got really good at telling crows from not crows, and we quickly added other birds into the mix. Now, she’s a full-fledged (pun intended) birder.

When you first mentioned doing Crow Not Crow as a picture book, I didn’t see it. I hadn’t written in any kind of illustrative medium and hadn’t yet learned to think visually while writing. But after writing three graphic novels with you, I was suddenly eager to work on Crow Not Crow.

JY: That is the core of writing picture books–thinking visually. You have to think in double page spreads, as scenes. You have to understand what makes the reader want to turn the page. But you also have to think like both a poet and a storyteller–compression and expansion. How to tell the story as if it is as tight and lyrical as a poem. (And I DON’T mean it needs to rhyme!)

Of course, adding the fact that we were two people writing one story from the point of view of a child only made it harder. It sounds really complicated put that way–but in the end, it was as wonderful as a dance.

AS: I like the fact that the form is compact and constrained. Constraints help me be more creative. I’m forced to rethink all the crazy ideas I have and mold them into a usable, readable shape. It’s that shaping that makes them come to life. Without constraints, I fly off into the ether, ending up with pages of stuff that gets tossed in a drawer, never to be seen again.

JY: I agree–there is something to be said for constraints in art. You learn them so you can eventually change, reorder, even violate them. A picture book–like a sonnet, a haiku–has certain parameters. And we slip into them as if putting on a special outfit: the ballerina has her tutu and toe shoes, the football player has pads, and clowns a red nose. We write picture books knowing the page count, understanding the page turn, aware of the child audience. Constraints but not restraints. Like grammar, we need it at the base of our picture book.

But I also love to work on books with you–and your brother and sister. Such partnerships come with other constraints. Family meetings without the fraughtness. Yes, you and your siblings are all truly good writers. But even more, when we work together on books, we deepen and broaden our relationships, for now we have more than just family gossip to sustain our visits. We talk art, craft, business–and new ideas as well. Besides, in books like Crow Not Crow, we bring back great memories of your dad, and what a wonderful husband and father he was. Not only did he teach all of us to bird, and was unsparing in sharing his own knowledge of the outdoors, he was also a great first reader for me. I know he would have loved this book because–as the original inspiration for Pa in my book Owl Moon–he cared deeply about good, honest, and lyrical books for kids about the natural world.

And when we write something like Crow Not Crow, it becomes a part of his legacy.