This month’s PB review is by Ryan G. Van Cleave (Amateur Travel Aficionado at Only Picture Books) and OPB newcomer Edna Cabcabin Moran.

–Ryan’s Review of the Writing–

In 1930s America, segregation was legal, and that meant Black Americans couldn’t do many of the things others could simply because they were Black. When New York mail carrier Victor Hugo Green found a guide for Jewish people that listed stores that sold kosher food, he got an idea. What if he put together his own guide that shared information about where Black Americans were safe and welcome?

Opening the Road tells the story of how Green got the idea, created the first guide, expanded it because of increasingly popular demand, and ultimately changed the lives of countless people because it offered Black people a list of safe places they could trust. He sold a lot of copies of his guide even before a national gas station chain started stocking it. Before long, the US government dubbed “The Green Book” an “official Negro travel guide.”

Green’s dream was that his guide would one day become obsolete, and in 1964, the US Congress “passed a law that made separating people by race illegal.” As a result, notes author Dawson, the 1966–67 Green Book was the very last edition ever published.

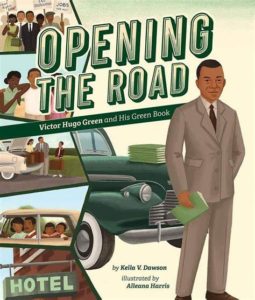

Dawson’s prose throughout the book is understated, which is an interesting choice considering the emotionally charged subject matter. Since the flip side is potential melodrama, it’s a tough balance to negotiate–no doubt about it. Another challenge nonfiction picture book authors face with subject matter like this is finding ways to engage children in a story that doesn’t feature children. Right on page one–as well as the cover–Victor Hugo Green is an adult. Perhaps what draws child readers are phrases like “a make-do toilet” and “sold like hotcakes!” or Alleana Harris’ potent illustrations which show conflict via contrast in many pages.

I’ll let Edna explain what’s going on with the art, since that’s her expertise.

A two-page Author’s Note supported by a two-page timeline helps contextualize Victor Hugo Green’s life and historical contribution. It also connects this story to Black Lives Matter and includes a clear call to action to fight injustice.

Opening the Road is fundamentally about the power within all of us to make a difference and change the world. It’s a clear must-have for public and school libraries. Adults who want another avenue to discuss the power of the human spirit to resist might find this an apt conversation starter, too.

4.25 out of 5 pencils

–Edna’s Review of the Illustrations–

The visual story of Victor Hugo Green and his Negro Motorist Green Book springs off the page in Keila V. Dawson’s Opening the Road thanks to illustrator Alleanna Harris’ intriguing combination of painterly and minimalist renderings. Harris’ keen digitally-created melding of artistic expression and socio-political references offers a frank, unsentimental, and impactful view of Black peoples’ experience in mid-century America.

Harris’ illustrations open on a strong note. In the first double-page spread, the bold shape of a two-lane highway shown in one-point perspective juts out from behind a minimally rendered car. Harris cleverly frames the faces of a frustrated Victor Hugo Green and his worried wife, Alma, with the simple form of a windshield. Through textural brushwork and thoughtful design, Harris sets a compelling stage for the Green Book’s inception and journey.

In subsequent pages, Harris composes painterly settings and deceivingly simple layouts that indicate a deeper narrative around Jim Crow rules: Long-distance travelers, unable to stop at a highway café, continue down a lonely stretch of highway; a white girl and a Black girl, with their backs to one another, walk away from segregated water fountains stationed at the center of the double-page spread; and in the first set of one-page illustrations, an image of a Black driver being told to leave a “sundown town” is juxtaposed with an illustration of Black children being kept out of a playground. Each of these scenes is powerful on their own but in succession they form a gripping visual tale.

Harris’ work is reminiscent of the architectural and scenic treatments of mid-century painter, Edward Hopper, as well as illustrative styles from the Little Golden Books of the same era. The first two-thirds of illustrations for Opening the Road are marvelously executed, setting up an expectation of continued dynamic page design, engaging sequential narrative, and fully-rendered paintings. Yet, the final double-page spreads fall a bit short. The bottom sections repeat the pattern of images in the lower half of the page and text at the top, and there are no textural treatments or background elements to draw one’s eyes up and around the pages.

The scene depicting protestors in the bottom foreground of the spread is interesting but the digital technique of repeating the crowd and blurring them out is a departure from Harris’ painterly handling of background elements. Plus, the blurring calls attention to itself. In the page spread that follows, a gray-haired woman sitting at a desk with Victor is placed in the bottom foreground, while the background is rendered with blue lines and light blue shading. The blue lines remind me of non-photo blue pens and pencils used in sketching and art production. This treatment and style is yet another departure from Harris’ painterly renderings such as that shown in the kitchen table scene of Victor and Alma writing letters.

Overall, I enjoy Harris’ illustrations and narrative voice and would’ve appreciated the same consistency and dynamics of the early pages in the final spreads. For me, the layout and style choices are a missed opportunity at bringing the visual narrative full circle. Yet, I had a change of perspective on the last double-page spread with its layout split in half by the illustration at the bottom and the text on top, against a paper-white background. I wondered if the visual “questions” of the first spread were answered by the last spread. (This is based on a writing tip offered by acclaimed author, Jane Yolen—that good endings “answer” the questions in a story’s opening).

I came to appreciate that Harris does answer the opening spread with her depiction of a present-day Black family (on the bottom half of the page) traveling in a car that “drives” to the right, into the future. The characters’ expressions are happy and hopeful, conveying Victor’s dream of “no Green Book for Black people.”

Lastly, nonfiction picture book backmatter often includes spot illustrations that add interest and round out the feeling of the book. The author notes pages are text-heavy and devoid of images, so I am glad to see Harris’ charming illustrations in the fun timeline of the Negro Motorist Green Book.

4.25 out of 5 crayons

Edna Cabcabin Moran is an author/illustrator, poet, arts educator, and hula dancer. Having been raised in the continental US east and west coasts, Iceland, and Hawai’i, Edna’s approach to storytelling and teaching is informed by her multicultural experiences and rooted in her arts-integrative practices.

Edna Cabcabin Moran is an author/illustrator, poet, arts educator, and hula dancer. Having been raised in the continental US east and west coasts, Iceland, and Hawai’i, Edna’s approach to storytelling and teaching is informed by her multicultural experiences and rooted in her arts-integrative practices.Edna’s latest picture book is Honu and Moa (BeachHouse Publishing), a Hawaiiana mash-up of the Tortoise and The Hare and recipient of a 2019 Aesop Accolade.