To understand why Brooke Vitale has been on the OPB Must-Interview list for some time, one need only look at three numbers.

- 100+ books written

- 750+ self-published books edited

- 1,500+ traditionally published books edited

If you want a bonus number, try this:

- 350+ of the books she’s been involved with have earned 5‑star ratings

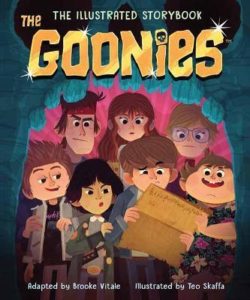

Or look at a few of her own recent picture books!

So, yeah, she knows her stuff as both an editor and author. That’s why I let this interview run a bit longer than the norm–she has SO MUCH to offer. See for yourself!

RVC: When did you first realize you were a writer?

BV: Honestly, I didn’t realize I was a writer until my job threw me into having no choice but to write. One of the things that I think a lot of people don’t know about publishing companies is that lots of the books are written in-house by the editors because the publishing company can’t necessarily afford to hire an author to write something that’s going to sell for $7.99. So, it falls on the editors to go ahead and write it. And also to come up with the idea for the book, to look at the list, and say I don’t have anything for Valentine’s Day—I’d better write it and hire an illustrator quickly, then rush it out the door.

Actually, that’s how some of my favorite books came about. For example, when I was at Penguin, my designer happened to be a paper engineer. We did a book called Everyone Says I Love You, which was about the words “I love you” in different countries. I wrote it, and he did the pops, and it was gorgeous.

It was when I really started doing all of that that I learned I could write. And of course, the more you do, the better you get at it.

RVC: When you’re an editor who’s also authoring books for the publisher, do you get treated like an author?

BV: Not only do you not get treated like an author, chances are good that you don’t even get to put your name on the book. It’s just “We need to have books on our list. I will do better if I can keep the list going and keep sales up. I will get a promotion if I can bring in X amount of dollars. So, let me write this book and move it along.”

RVC: Let’s leap back to the beginning of your career. What was your pathway to becoming an editor?

BV: This probably wouldn’t surprise anybody given that I work in books, but I was that kid who was happiest being in my room. Reading. Even in college, I did a lot of reading.

RVC: You and me both!

BV: I went into school thinking I was going to be a physical therapist, and then I took chemistry and that idea went away. Then I went into psychology and really didn’t like it, so I ended up an English major with a focus in children’s books because I could graduate and figure it out later. I remember talking to a friend one night during my junior year of college, trying to figure out what am I going to do with myself. I asked, “Why can’t I just have a job where I read all day?” And my friend said to me, “You know, there’s a whole industry around that, right?”

Honestly, no—the fact that there were people who put the books together had never occurred to me as a career path. I was lucky enough that this friend actually worked at the university press, and she was able to help me get an interview there. I interned for one semester at the University Press of Florida and realized that I liked it. Afterward, I applied to graduate school at NYU, where I got my Master’s in publishing. And while I was there, I managed to land a general internship at Sterling Publishing, which is a company owned by Barnes and Noble.

RVC: What was it like at Sterling?

BV: Sterling did a lot of DIY books. That was what they had done for years. I walked into the office my first day, and they showed me this stack of paste-ups for books. Literally, what that means is that the pictures used to be glued to a board, and the text used to be typed up and pasted to the board, and then they would scan it that way. So I got there and they said, “We need you to take all the pictures off and find the author. Hopefully, the author is still alive! And we need you to mail everything back.” This was how I started my career in publishing—pulling 30-year-old pictures off of paste-ups in a dusty room.

After I’d been there about six months, a position opened in the children’s department. I had gotten to know the editorial director there, Frances Gilbert—who is now over at Random House—and she hired me on. That was how I got my start. She taught me everything. I learned so much working from her. And some of my favorite books I ever worked on were done there. Like Who’s Haunting the White House, which was a nonfiction about all the ghosts in the White House. It was such a fun book, and she really helped me shape it!

After I’d been there about six months, a position opened in the children’s department. I had gotten to know the editorial director there, Frances Gilbert—who is now over at Random House—and she hired me on. That was how I got my start. She taught me everything. I learned so much working from her. And some of my favorite books I ever worked on were done there. Like Who’s Haunting the White House, which was a nonfiction about all the ghosts in the White House. It was such a fun book, and she really helped me shape it!

That’s the thing about publishing—it’s a mentorship business. You really have to find somebody who can teach you how to do the job, because you can’t teach it to yourself. You need someone who will sit and do an edit with you and teach you why they’re making those decisions. And what’s going to make a good book, as well as what’s not going to make a good book.

RVC: Let’s talk Disney. You worked there for seven years. What kind of hurdles did you face as an editor there?

BV: Working with the studio was one of the bigger challenges. They have really specific things that they’re okay with, and really specific things that they’re not okay with. The thing is, as an editor, you’re always getting on calls with the movie producers—both from current movies and ones that are years old! They’re looking at everything. They’re approving everything to make sure that it’s on brand, because the goal is always that they’re going to put out more movies, more shorts, whatever it is. And you, as the publishing arm, have become the storytelling arm of extending their brands. They need to know that you’re not doing anything that will then be at odds with their plans. Which means that sometimes you have to make changes you don’t expect.

RVC: Got an example?

BV: Sure. I remember working on this one book, A Frozen Heart, which was basically a retelling from the dual perspective of Anna and Hans. And they said, “You cannot say at any point in this book that Anna wants to find love.”

BV: Sure. I remember working on this one book, A Frozen Heart, which was basically a retelling from the dual perspective of Anna and Hans. And they said, “You cannot say at any point in this book that Anna wants to find love.”

I said, “She sings an entire song about that.” And they said, “Yes. But you can’t do it.”

Whatever the reasons were, they had them, so we worked around it. But that was always the biggest hurdle—managing the needs of the studio, because everything we did ultimately came from them. They had to be happy with the end product and managing the needs of a good book.

The two aren’t always the same thing.

RVC: Here’s the question every writer wants me to ask. What’s the secret to getting to write a book for Disney?

BV: Know somebody. Honestly, that’s the secret. Most of the people who are hired to write a Disney book are industry insiders. We tend to turn to writers and editors that we know. We KNOW that they know the license and can knock it out of the park.

There will be other opportunities occasionally because things have changed in the last few years for Disney and the world as a whole because of the need for diversity and inclusiveness. For example, when Disney put out Moana, we weren’t allowed to bring on a single person to write or illustrate unless they had a Pacific Islander background. The same happened when they put out Coco.

I know somebody who just wrote a book for Luca, but she’d never done anything for them before. But she knew somebody who knew somebody, and they said, “We need someone who fits this mold, because we want to make sure that what we’re writing is true to the culture.” So, there’s always the chance that somebody’s going to find you and ask you to come in and do something. But unfortunately, it really is who you know.

RVC: Wow.

BV: There’s probably only 100 freelance writers out there who are doing all of the writing for every licensed product across publishing.

RVC: Does that feel like a lot to you? Or does that feel like a small number in your perspective?

BV: It’s probably about right. When I worked at Disney, I had about 12 to 15 authors that I went to every single time. Across our entire group at Disney, we had maybe 25 authors that we were turning to, but a lot of those are the same authors I was turning to when I was at Penguin. You take who you know, you take who you trust, you take somebody who’s maybe been at that company before and understands how it works.

Licensed publishing is its own unique piece, again, because of all the approvals processes, and that an author doesn’t necessarily have the freedom they would have if they were writing something for themselves. There are a lot of rules around what story they need to tell. There are a lot of rules around how a character can develop, and you need somebody who isn’t going to pitch a fit if you come back after you told them the manuscript is perfect and then, suddenly, the whole thing has to change.

RVC: I’m sensing that this has happened to you a few times.

BV: It’s happened to me as an editor and an author. A few years ago, I was writing a book for Scholastic around Disney’s Kingdom Hearts. We were under the impression that we could do one thing. My editor asked me to write the first three chapters, which I did. And then when it went off to all of the licensors—there are several tied to that franchise—they came back and said, “We’re not actually comfortable with this after all. Start from scratch.”

It’s one of those things where you go, “Okay, that’s the business.” You can’t mess with future plans.

RVC: Let’s talk a bit more about editors. Is it accurate to say that there is more than one type of editor at a traditional publishing company?

BV: That’s right. You have editors who are acquiring and editing books, and then you have the editors who are coming up with their lists, writing them, and getting them out the door.

So, for a traditional picture book, you’re going to have an editor who is getting all of the manuscripts in from agents. They’re looking at everything, they’re finding what they love, and they’re picking out the few that they really, really love, because the publishing house can only publish so many books in any one year.

A house might have an imprint that has five editors who are acquiring manuscripts. For any given season—which is how scheduling is broken out for publishers, with two or three seasons per year—you might have only four or five books each of them is working on. So, they’re finding the ones that they really love. They’re bringing them to the editorial group and the rest of their team, saying, “Do you love it as much as I love it?” Then they’re bringing it to a sales and marketing team and asking, “I love this, but can we sell it?”

As an editor, you need to have a sense of the market. You need to know that this really is something that can be sold, but it’s still going to come down to a sales and marketing thing. They might say, “It’s great, but I think I can only do 600 copies,” or they might say, “I think I can do 10,000 copies.” That input is going to make a big difference. But once an editor gets that yes, an editor’s job is to shape the story. That means working with the words, but also commenting on art and design, shepherding the book through the whole publishing process. A book’s success reflects on the editor, so it’s their baby to oversee from start to finish.

RVC: What do most people not appreciate or understand about an editor?

BV: I hear from a lot of people who say, “A publisher is just going to tear my book to shreds. It’s not going to be my book when they’re done with it.” I think the most important thing for anybody to understand about an editor or acquiring a book at a publishing house is all of the hoops that an editor has to jump through to be able to acquire your book. It’s not just one person saying, “I love it, and I’m taking it.” It’s also that editorial group, the sales and marketing group, and it might even be taken to Barnes and Noble and Amazon to see if they think that they can sell it.

Any book that’s coming from agents is going to be in a good place to begin with. It should be something that has enough promise that an editor feels they can get it where it needs to go. The editorial process is about going back and forth with the author, finding the things that can change as well as the things that NEED to change. And sometimes there really are things that NEED to change. For example, is this a book that Scholastic would take? They only take clean books. They don’t want anything that’s going to cause a parent to say, “Wait a minute, I’m not sure about this.” So, sometimes an editor has to go back to the author and say, “I know you love this part, but we need to change it.” Or, “I know you love this, but we’re talking about the difference between 2,000 units and 20,000 units.”

But here’s the thing. At the end of the day, an editor’s not acquiring anything they don’t love already. They don’t want to tear it to shreds—they want to make it as good as it can be.

RVC: In 2017, you shifted your career to freelancing. As a freelance editor, what’s the process you use when someone hires you to work on their picture book manuscript?

BV: I always break the manuscript down into two different pieces. I start with what I call an assessment, and that’s when I’m looking for all of the big problems. It’s pretty rare that I get a manuscript that doesn’t have at least a few big problems, like you’re telling me what’s happening instead of showing me what’s happening. Or there’s not enough emotion here—that happens a lot.

I’m also looking for potholes. I’m looking for places where something doesn’t make sense or is handled ineffectively. I had one manuscript come to me about a year ago, and I said to the author, “You’re going to hate me, but you’ve written this entire book from the wrong character’s point of view. This isn’t their story.” He looked at it and said, “Okay, I’m going to try.” He rewrote it. He later told me that he thinks it’s now 1,000 times better.

And of course I’m looking at word count. For a picture book, you can’t have 45 words telling me what somebody looks like when I can look across the page and see that for myself. All of those things need to go. A story needs to move along at a fast clip. It needs to keep a child’s attention. There are just so many stories that get bogged down in details that aren’t necessary. Sometimes details do matter. But it’s not necessary most of the time. Remember—a picture book audience is three to seven. They have no attention span. If you’re not moving the story along, and if with every page turn, you’re not shifting scenes or shifting emotional moments, you’ve lost your reader. They have gotten up and walked away to go find toys to play with, or different books to read or whatever it might be.

After handling a large-scale assessment on the manuscript, I perform my developmental edit, which is really just finessing it, bringing it all together, figuring out the actual words, determining where page turns will go, and offering up art notes for the illustrator.

RVC: Where does rhyme fit in here?

BV: There are two ways of writing a picture book. Either you write it in rhyme—which so many love to do—or you write it in prose.

With prose, it’s really easy for a reader to stop and say, “What does that mean?” and not lose the thread of the story. It’s a lot easier to use big words in prose. But when you’re rhyming, if a kid stops because they don’t understand that word, you’ve not only stopped the story, you’re asking the kid to reset their head back to the meter of the rhyme. That’s a big part of editing rhyme—looking at your meter. If you’re rhyming, are the beats hitting exactly where they need to hit? If a reader’s stumbling over the words, it ruins the whole reading experience. It’s got to be seamless.

All of that is what goes into making a manuscript sing—making sure the kid stays engaged and wants to turn the next page.

RVC: What tips do you have for taking rhyming that’s draft-good and making it publishing-quality good?

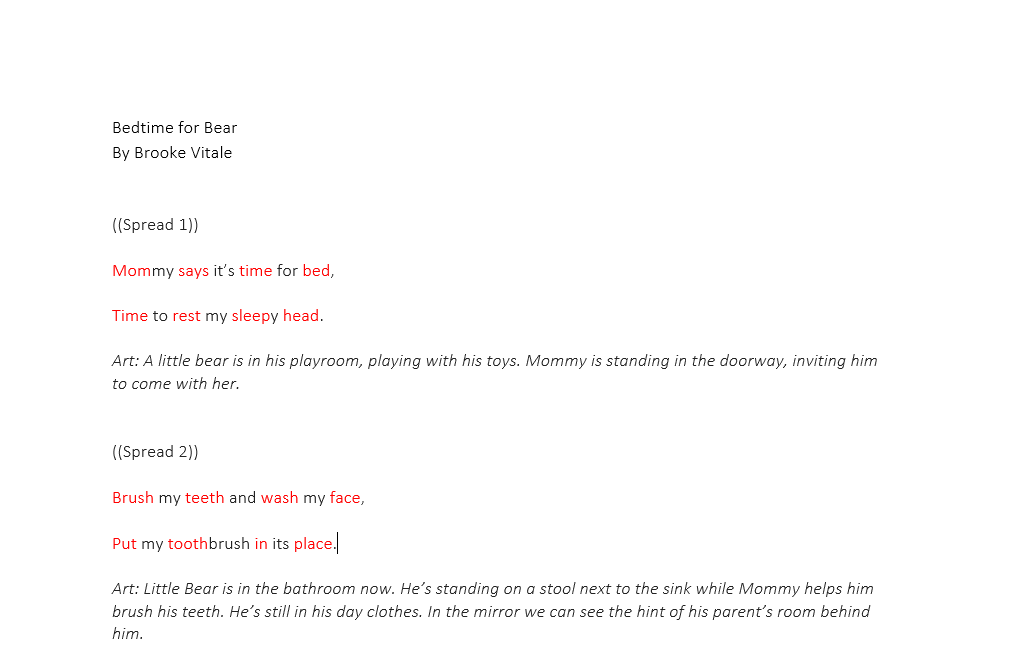

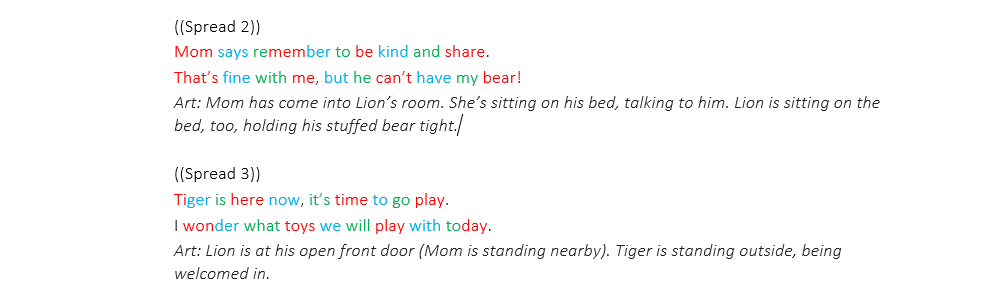

BV: There are two big problems with rhyme. Like I said before, one is not understanding meter.

The most common kinds of meter used in picture books are an iambic meter, which is stressing every other beat, and an anapestic meter, which is stressing every third beat. I recommend that writers literally stand there and clap out what they’ve written—clap hard for a stressed, and give a little clap for non-stressed beat.

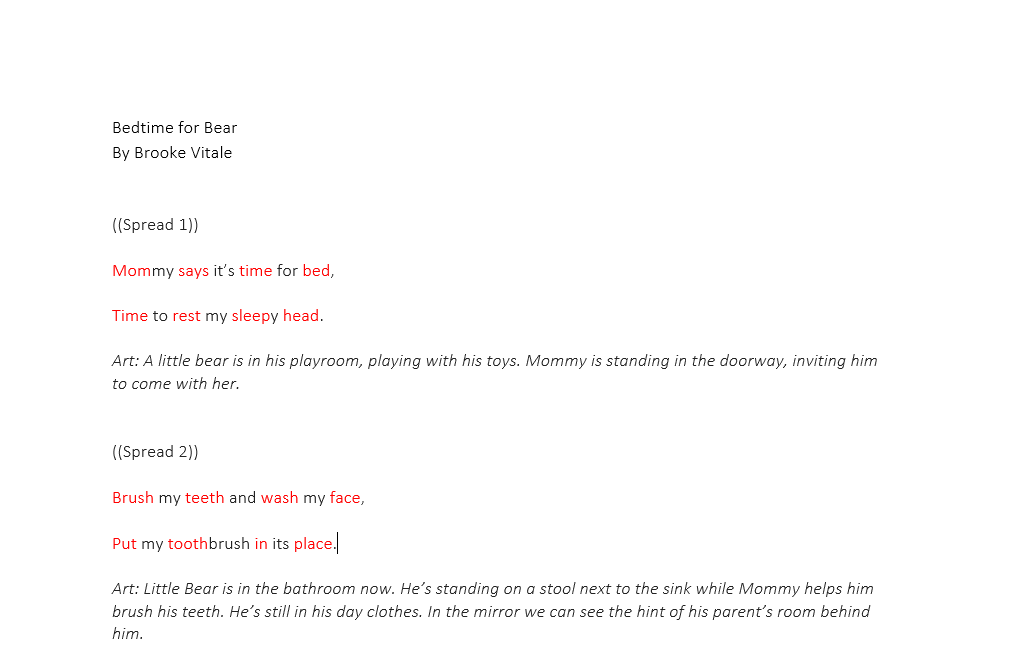

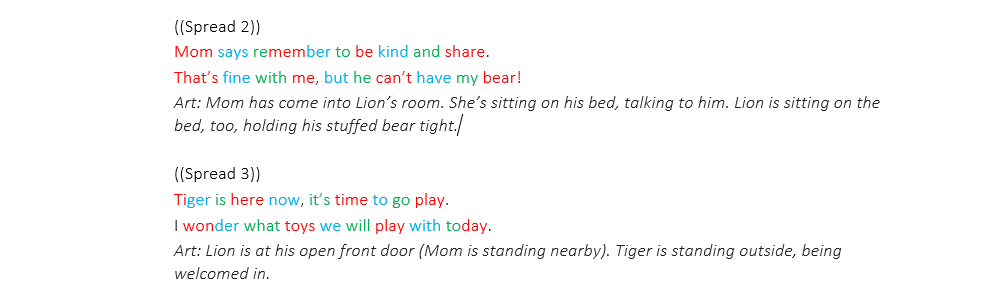

For visual people, I color code everything. For iambic meter, my stressed beat is red, and my downbeat is black. Like this:

For anapestic, I do it a bit different. I keep my stressed beats red. My first downbeat is blue and my second downbeat is green. Then I’m back to my next red stressed beat. If the line isn’t following that pattern—if I have red, blue, green, red, blue, green … uh-oh, there’s an extra thing there—something’s not right.

Those are my top two ways to nail meter. As far as the rhyme itself, the biggest problem I see is either using words that don’t rhyme at all, or using words that are a near rhyme. It’s just so important with a rhyming book to make sure that the words you’re choosing to go with the end of the line ACTUALLY RHYME. “Talk” and “walks” don’t rhyme because the S at the end of “walks” throws it off. Yet I see things like that all the time. I always recommend people go to the website, Rhyme Zone, where you can type in a word, and it’ll tell you what actually rhymes. I use it myself all the time just because sometimes you get stuck.

If you can come up with true rhyme and use meter well, you’ll be in a good place most of the time.

RVC: Any warnings about rhyme?

BV: Rhyme doesn’t work well with heavy topics. It’s really hard to have an emotional punch in a picture book when you’re trying to use small rhyming words. When something’s especially dark or deep, I usually suggest taking it out of rhyme.

RVC: What type of clients do you get for your freelance services?

BV: Many of the authors that I work with are actually looking to self publish at this point. They’re looking at the difficulty of getting into a traditional publishing company. And they’re looking at the royalty structure of a publishing company and knowing that, unfortunately, publishers have maybe 10 lead titles out of the year. That’s where they’re putting their marketing dollars. So, all of the marketing efforts still has to go to the author. At a publishing company, they’re also only getting 10% of the profits instead of 100%.

While there absolutely are benefits to publishing companies—and don’t get me wrong, distribution is one of the huge ones—a lot of my authors want more creative control. They’d like to be the ones who are benefiting from their own work.

RVC: You’re still doing a lot of picture book writing, and many of those are with existing franchises. How are those happening?

BV: Like I said, it’s who you know. My colleagues from Disney and Penguin are at all the big companies now. One of my bosses at Disney is now the editorial director for Lucasfilm. So, the first season of The Mandalorian came out and they needed books. I got an email and he said, “I need three books, and I need them in seven days.”

BV: Like I said, it’s who you know. My colleagues from Disney and Penguin are at all the big companies now. One of my bosses at Disney is now the editorial director for Lucasfilm. So, the first season of The Mandalorian came out and they needed books. I got an email and he said, “I need three books, and I need them in seven days.”

So, I got them to him in four days.

RVC: I’ve said it before, but here it comes again: Wow.

BV: Yeah, that one was fun. Lots of hours on the couch watching TV! But really, it’s those existing relationships. Children’s book publishing is a really small world—there are very few people that you don’t know, or know in passing. Licensed publishing is an even smaller world, because each company is going to have one imprint that’s going to be doing it. Penguin has Penguin Workshop. Simon and Schuster has the Simon Says imprint, etc. All of the editors are moving around within a circle, and they’ve got their go-to people.

RVC: Do you ever get hired as an editor on a project-by-project basis with traditional publishers?

BV: I still do a lot with publishers. I was just hired by a publisher to work on all of their readers. I do a lot with Sourcebooks as well because my former boss is now their custom sales person. She’ll call me and say, “I need you to just take over this project because I know that you know their requirements and know you know how it has to go together—your understand the format.”

RVC: And custom sales are … ?

BV: Nonreturnable books created specifically for a particular store like Costco or Target.

RVC: Gotcha. What role does your family play in your writing or editing process?

BV: Not so much in the editing process. That tends to happen when I’m by myself, because the only role that my children play is being very loud, and it’s hard to edit when they’re screaming behind me.

But in the writing process, they actually do play a big role. And it’s funny, several of the books that I’ve written at this point have come about out of conversations with my husband. He used to say to me, “Why are you editing other people’s books? You should be writing your own book.” And I always said, “I don’t have anything original to say.”

Then he started throwing ideas out. “Well, why don’t you write about this?” I thought, “Okay, well, that sounds kind of fun. Let me noodle around with it for a while.”

And then the next thing you know, I’ve got six books sitting on the back burner, ready to do something with them. Because we do a lot together, there’s a big collaborative process around ideation. And because he’s a very critical person—not in a bad way—he will read something and tell me if it’s garbage. I know that if he’s not laughing at it, if he’s not smiling, I have to go back to the drawing board. If I get a chuckle out of him, I’m probably onto something.

RVC: What’s his background?

BV: He’s in real estate.

RVC: Sometimes non-writers are the best beta readers.

BV: Totally. I read all my books to my kids. If they like them, I know I’m doing well. If they tell me it’s boring and they walk away, then I’ve got to make changes. They’re the target audience.

RVC: Before we end this first part of the interview, I have to ask—what is Charge Mommy Books?

BV: When we were stuck at home last year because of COVID-19, I played out in the backyard a lot with my almost four year old and almost six year old. They started this game where they would literally pick up a baseball bat and run at me with it. They called it Charge Mommy. What I had to do was grab the bat in my hand and send them around in a circle, and then let go. They’d fall back on the ground and crack up, laughing, then they’d say, “Let’s do it again!” This became a common game in my house—Charge Mommy!

BV: When we were stuck at home last year because of COVID-19, I played out in the backyard a lot with my almost four year old and almost six year old. They started this game where they would literally pick up a baseball bat and run at me with it. They called it Charge Mommy. What I had to do was grab the bat in my hand and send them around in a circle, and then let go. They’d fall back on the ground and crack up, laughing, then they’d say, “Let’s do it again!” This became a common game in my house—Charge Mommy!

During that time, I started jotting down ideas for books. And because I actually had some time on my hands, I was able to start thinking about writing them and thinking about what it is that I like about books that I want to put out in the world. So, Charge Mommy Books is an independent publisher. And our focus is twofold. One is on publishing books that children can enjoy reading and want to read again and again—they’re just good, whimsical fun, and aren’t meant to teach about an issue or not meant to cover a problem in any way but just be something that you can enjoy. And the other piece of it is that we strongly support literacy, because it’s really important to us that children do learn how to read.

We’re starting with a handful of early readers that we’re dropping on Instagram right now, one page at a time, with a literacy activity that goes with each individual page. And we’re working with a literacy specialist to make sure that those are actually geared toward the right age range. What we really want and the reason we’re doing it on Instagram is because we know how much time parents spend on their phone. We want to give them a moment to engage with their children. Let’s look at this together. Let’s make this a useful technology moment.

We’re also planning to donate a portion of all of our proceeds to literacy foundations. I’m based in Connecticut, and there are certain areas here that don’t have the support they need, though there are obviously areas in New York City that could use our support, too.

RVC: Last question for this part of the interview. When will the first Charge Mommy Books be available?

BV: We’re looking at doing a pre-order on our first round of books, probably in December, with books to be available in the spring. Our list will be a mix of books written by me and books that we are republishing by authors whose rights have reverted back to them.

RVC: Okay, it’s time for the Lightning Round. Zippy zappy Qs and As please. Are you ready?

BV: Absolutely!

RVC: Your favorite eat-out place in Connecticut?

BV: Garden Catering is a little place here that has turned into a chain. They have the best chicken nuggets and French fries, plus these things called cones that are like tater tots, but puffier.

RVC: Your favorite Disney villain?

BV: Maleficent.

RVC: Biggest time waster?

BV: Internet—Instagram, Facebook, social media.

RVC: A recent picture book that really got your attention.

BV: One of my favorites is Calvin Gets the Last Word, which is from the perspective of a dictionary that has a boy who carries it everywhere to look up words. And it’s one of those stories that uses words that are well outside of the child’s understanding but still uses them properly. The end sheets actually give the kid version of the definition of those words. I think it’s so well done. Brilliant. It actually opens up conversation about bigger words, the importance of words. I’m loving it.

BV: One of my favorites is Calvin Gets the Last Word, which is from the perspective of a dictionary that has a boy who carries it everywhere to look up words. And it’s one of those stories that uses words that are well outside of the child’s understanding but still uses them properly. The end sheets actually give the kid version of the definition of those words. I think it’s so well done. Brilliant. It actually opens up conversation about bigger words, the importance of words. I’m loving it.

RVC: What’s the most important trait you bring to the keyboard?

BV: It’s my problem solving. There are a lot of veterans out there who will say to somebody, “It’s not working!” But “It’s not working!” doesn’t get you very far. It has to be, “It’s not working. And here’s how we fix it.”

So, what I bring to the keyboard is the “Here’s how we fix it.”

RVC: Your proudest moment as a writer?

BV: I think my proudest moment as a writer is probably still coming. Though I have a picture book retelling of The Goonies coming out next month that I’m quite proud of.

RVC: Thanks so much for this, Brooke. You were terrific!

David C. Gardner is an award-winning illustrator and visual development artist. A former artist for Walt Disney Animation Studios, he has illustrated numerous picture books, including his latest from Sleeping Bear Press,

David C. Gardner is an award-winning illustrator and visual development artist. A former artist for Walt Disney Animation Studios, he has illustrated numerous picture books, including his latest from Sleeping Bear Press,