This month’s Author Interview is with the amazing Helaine Becker! Welcome, Helaine!

Helaine is the author of 90+ books for kids, and she’s written for children’s magazines and children’s television, including four seasons of Dr. Greenie’s Mad Lab. She attended high school in New York and graduated cum laude from Duke University “in another century,” she notes with a laugh. She’s married, has two sons, and is an active swimmer, artist, miniaturist, and compulsive read-aholic.

Some fun facts about Helaine:

- “I have an orange belt in karate and am contemplating going for my grapefruit belt!”

- She once won an owner/dog look-alike contest.

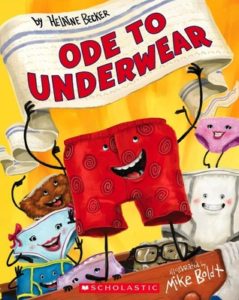

- Her book Ode to Underwear was set to music by the popular Canadian band, The Irish Descendants, and played nationally on CBC radio.

- She’s a certified pyrotechnics practitioner, so expect KABOOMs when she’s around.

- She’s building sets for stop-motion animation–just for fun.

- Helaine frequently volunteers her brain for research…as a study ‘control.’ (“That means my brain is the normal brain they are using for comparison in scientific studies. Now THAT’s funny!”)

And here’s some social media and web stuff.

And here’s Helaine’s eyeball, because she says “who ever includes pictures of their eyeballs?” Helaine does. That’s who!

Now that we have a pretty good basis for a literary friendship with Helaine, let’s get to that interview!

RVC: You’re living in Canada, right? I’ll resist using my terrible French during this interview since you probably speak it far, far better than I do.

HB: No, probably not. Toronto is an Anglo city. If anything, you’d be more likely to speak Mandarin or Italian here. There’s a half a million Italians and probably close to that of Mandarin speakers. We have about 87 different languages spoken in the public school system.

RVC: Wow, that’s a lot. But just to be clear, you have both American and Canadian citizenship?

HB: That’s right.

RVC: But you’re from The Big Apple originally.

HB: I am from New York. When I go back there, I always think,“This is so provincial, this town.” They’re so in their own navels, like God, they don’t know anything about anything. And I would have never expected that growing up when I thought New York was the center of the universe, the be all and end all.

BTW, I ADORE New York. Especially the pizza.

RVC: When did you move to Toronto?

HB: I moved here in 1985 because I’d met my husband in university, when we were both going to school in England, and he’s Canadian. So, when we all finished school, and it’s like, he could come to New York, or I could come here and at that time, you couldn’t get any job in New York as a foreigner because it was one of those you-need-a-green-card deals, but you couldn’t get a green card. So I just said, “Well, I like adventure.”

RVCF: When did you first know you were a writer?

HB: I was five. I knew it from the moment I first learned to read–it was such a big deal. I just loved it so much that I didn’t want it to end. I’d read Sam the Firefly, so I wrote my own Sam and the Ant. It wasn’t any good since I was five, but early on, that connection between reading and writing was there. I thought, well, real people write books, and I am a real people, so why shouldn’t I write a book? It never occurred to me that they were some kind of magic–I knew somebody had to write it.

HB: I was five. I knew it from the moment I first learned to read–it was such a big deal. I just loved it so much that I didn’t want it to end. I’d read Sam the Firefly, so I wrote my own Sam and the Ant. It wasn’t any good since I was five, but early on, that connection between reading and writing was there. I thought, well, real people write books, and I am a real people, so why shouldn’t I write a book? It never occurred to me that they were some kind of magic–I knew somebody had to write it.

In school I was always that kid who was making up stories and reading. The bookworm who wasn’t doing my math homework because I was too busy reading. But then I quit. I gave it up because at that point, I thought you have to be magic. That was a big mistake.

RVC: How did you find your way back to writing kidlit?

HB: I went to school, I had a career, whatever. But at one point, I just sort of said, “Well, I still want to be a writer.” And I was like 100 years old already. And I realized that I made a mistake by quitting in my teen years, so I decided to give it a go.

Now at that point, I had been writing curriculum in science and math, teaching materials for education, producers, curriculum and supplemental materials. I was a good writer. I come from a copywriting background, too, so in terms of publishing, I wrote the outside of the books. It was like, “Okay, I want to write the insides of a book now.”

It took about four years to have my first trade book published–that was in 2000. It was a book of poetry that never really got out of the gate. The company that published it–a major Canadian publisher–went bust. Like the following week. My book never made it out of the warehouse.

It took another four years before my next book was published, after that, it was smooth sailing. And it’s been 90 books since then.

RVC: Why write kidlit versus the educational and curriculum books?

HB: I’m childish, or childlike, as the case may be. So, I don’t actually write for children–I write things I like. Inside my head, I’m still an 11 year old. I really like all the things I’m doing. Building miniatures. Drawing. Making art. I was doing all that when I was 11, and now I get to do it again. So, I write what I’m interested in, and what I think is funny, and kids are interested in it and think it’s funny, too.

RVC: Humor is hard to get right in picture books. How do you handle incorporating humor?

HB: I was talking with kids at a school, and I challenged them. I said, “I bet I can make you laugh with one word.” They didn’t believe it. I said, “Underwear!” and they fell over, laughing. And they kept laughing every time I said it, as many times as I wanted to. I realized that if I read a poem with the word “underwear” in it, I am guaranteed a laugh. So, I sat down and I wrote the poem that became Ode to Underwear.

HB: I was talking with kids at a school, and I challenged them. I said, “I bet I can make you laugh with one word.” They didn’t believe it. I said, “Underwear!” and they fell over, laughing. And they kept laughing every time I said it, as many times as I wanted to. I realized that if I read a poem with the word “underwear” in it, I am guaranteed a laugh. So, I sat down and I wrote the poem that became Ode to Underwear.

RVC: To be fair, “underwear” is a pretty funny word. But how else do you make the humor-magic happen?

HB: I really like wordplay. The subject has to be funny, though the words, too, have to be fun and funny to say and hear. Certain words have funny sounds to them, like words with the letter K in them tend to be funnier than words that don’t have the letter K. As an example, which is funnier: “pail” or “bucket”?

Come on, it’s “bucket,” right? And then it’s a matter of doing the kinds of rhymes to make it fun.

But I also think life is funny. I mean, if there’s a world with teenagers in it, then the world is funny, because teenagers are just funny people, right?

RVC: As someone with two teen daughters, I full-heartedly agree. Teens are funny people.

HB:  My book That’s No Dino!: Or Is it? What Makes a Dinosaur a Dinosaur is a nonfiction picture book about dinosaur taxonomy. But you can make dinosaur taxonomy funny through the art, like with a creature character that has huge bulging eyes on stalks, right? It’s funny, but the book still gives you the information.

My book That’s No Dino!: Or Is it? What Makes a Dinosaur a Dinosaur is a nonfiction picture book about dinosaur taxonomy. But you can make dinosaur taxonomy funny through the art, like with a creature character that has huge bulging eyes on stalks, right? It’s funny, but the book still gives you the information.

Same thing with Emmy Noether: The Most Important Mathematician You’ve Never Heard Of, which was actually the hardest book I ever wrote. Did you ever hear of her?

RVC: I have, but it’s only because of your book.

HB: Oh, thank you, thank you, thank you!

HB: Oh, thank you, thank you, thank you!

With this book, we couldn’t quite figure out how to do it. We came up with these funny checklists at the beginning that described how she didn’t fit in with the prevailing things. For example, it says, “Girls were supposed to play the piano if their families were fancy.” And the book then says that Emmy was a lousy piano player. It’s fun.

RVC: Fun stuff indeed! Now, what do you think in the state of kid literature right now?

HB: We’re in a golden era. I think the books that we’re producing are better than ever. Picture books–they’re an art form, right? We know that they’re an art form. They’re not just books for kids who aren’t old enough to read words yet. I always think a picture book is like an opera on the page. Because it’s got set design, it’s got costumes, characters. It’s got music and the language. You’ve got everything in its story. The sophistication level is so high, because everything has progressed in history.

Take a classic picture book like Curious George. I grew up reading about George–I love that little monkey. But now you look at it and it just doesn’t have the sophistication or the depth you find in what’s coming out now on a daily basis. I feel very lucky to be part of this. And especially in Canada, where we have this wonderful collegial relationship with a lot of editors and other writers who are so fabulous. You really feel like you’re in the middle of something magnificent.

RVC: Let’s talk about one of your most successful books, Counting on Katherine. What’s the story of how that book happened?

HB: I’ve been a raging feminist since I was nine. And it really bugs me that 50 years has gone by, and things really haven’t changed that much.

HB: I’ve been a raging feminist since I was nine. And it really bugs me that 50 years has gone by, and things really haven’t changed that much.

I have two sons, and I raised them as a feminist does by saying, “Girls are smarter than boys!” into their little cribs. So they know girls are smarter than boys. That’s all fine.

My older son was working as a research assistant with me on a project I was writing a book for National Geographic–it was on space. One of the pages needed to list space pioneers. I said,” Okay, Michael, go find me some space pioneers, and you know what to get, right?” He said, “Yeah, yeah, no dead white guys.” I told him, “It’s not NO dead white guys, just not ALL dead white guys. Give me something else.”

He came back and said, “Mom, I found somebody new. You’re going to love her.” It was Katherine Johnson.

RVC: Way to go, son!

HB: Now at this point, Katherine Johnson was basically unheard of. Hidden Figures didn’t exist yet. In fact, when I got interested in Katherine Johnson, it was almost the same time that Margot Lee Shetterly was working on it.

I’d already been working on a book about Patsy Takemoto Mink, who was one of the architects of Title Nine, which is what An Equal Shot: How the Law Title IX Changed America was about. I couldn’t get any traction with it because people didn’t think that she was really discriminated against or did anything so great because she was Asian American, and a woman, and it was women’s rights.

I’d already been working on a book about Patsy Takemoto Mink, who was one of the architects of Title Nine, which is what An Equal Shot: How the Law Title IX Changed America was about. I couldn’t get any traction with it because people didn’t think that she was really discriminated against or did anything so great because she was Asian American, and a woman, and it was women’s rights.

But Katherine Johnson? I thought, “Oh, she’s got the whole package–tick, tick, tick.” I KNEW I could sell this. I had to get in touch with her, which wasn’t easy. She was 96 at the time, and not a lot of 96-year-old people have Twitter. It was quite a deep dive into the bowels of the Internet and phone records and history to see if I could come up with some kind of address to send a snail-mail letter to. I found something and sent it. About a month later, I got a letter back from Katherine Johnson’s daughter saying,” I got your letter. Mom would be happy if you wrote a book about her–especially for children–because she was a teacher. And we checked you out and my grandson has some of your books on our shelves, so we know you’re okay.” I passed the test!

RVC: You sure did. How did it go from there?

HB: It was a wonderful experience. I met the whole family. I did finally interview Katherine by telephone because her daughters didn’t want anybody going to see her without them being there. But we did the interview, and that’s sort of how it happened. Because my son knew a good idea when he saw one.

He gave me another good idea for a book, too.

RVC: What was it?

HB: Pirate Queen: A Story of Zheng Yi Sao. She was the most powerful pirate that ever lived. 80,000 pirates under her command!

HB: Pirate Queen: A Story of Zheng Yi Sao. She was the most powerful pirate that ever lived. 80,000 pirates under her command!

RVC: Wow!

HB: Yeah. But don’t you wonder why we never heard of her? Like, how ridiculous is that? Even in Guongzhou– which is where she was from–they don’t know who she is. But they know her husband, who didn’t do as well as she did. And they know her stepson/lover, who also didn’t do as well as she did.

She’d been erased from history. Until now.

RVC: They all need to read your book. Isn’t that what we’re saying here?

HB: Well, that’s why you write something–because it grabs you. You say, “I love this story. I need this story to be told. And if no one else is going to tell it, I’m going to tell it.”

RVC: How do you go from the idea of a nonfiction book to the words on the page? You’ve always got way too much material, don’t you? How do you chip away at it to get it down to size?

HB: Research is the important thing. When I’m in a classroom, I always say to kids, “You know that you have to write a rough copy first, right?” You have to do all your book research first, and then spit it out on the page and see what’s there. And you know how we call it “word vomit”? Because it’s always a hot mess, right? Then we go back through and figure out the highlights.

First of all, it’s knowing what’s interesting and what isn’t. This is mostly innate, I think. Some people love the research, and they love the fact that you read the book and you can see that they put everything they researched in, including the part about how they ate the live crickets. That’s really interesting! The part about how they went to such and such a school and did this and did that? Not so interesting! You’ve got to pick out the highlights. (Hint: Crickets! Always go with the crickets!)

Then you have to put it together into a story. Even a book like That’s No Dino!. It’s nonfiction. It’s facts! You still have to see it, though, in terms of a story. There needs to be some kind of arc–there needs to be some way to keep turning the page. Why are you going to turn it? What’s pulling you along through the story? And then there’s the editing–the honing, honing, honing. To me, that’s the essence, and it’s work. Nobody wants to do it.

Kids are always like, “I want to write the rough copy and it’s good.” Well, it isn’t. And the difference between the kid that gets an A–or the published author–and everyone else is that they don’t stop at the first draft and say it’s good enough. They keep at it and keep working and keep working until they’ve really honed it.

RVC: Good enough isn’t good enough.

HB: Exactly. And then you give the manuscript to someone and they say, “Hmmm, I didn’t really get this.” Now, I don’t know if you’re like me, but that’s when my ego always comes in. My automatic reaction to a critique is: “You’re an idiot.” That’s ego.

Then I realize that even if that other person were an idiot–and they’re not because they’re your friend or colleague or editor or whatever–as a writer, it’s your job to clearly communicate what you’re trying to get across. So you go back and ask, “What wasn’t clear?” and you then make it clear such that everybody who picks up your book is going to follow it.

RVC: Let’s stick with this idea of problems in story drafts. You’re often a judge for kidlit contests, which means you read a ton of manuscripts. What are three of the common issues you see?

HB: The number one mistake that most people make when they’re beginning is they forget that a picture book is primarily a story. A story means having:

- a beginning,

- a middle,

- and an end.

And there are a lot of books that you see that are merely concepts. Like, I have an idea about the baboon that climbed on the roof of the school and was banging on the ceiling. Okay, well, that’s not a story. That’s an idea. You have to make a beginning and a middle and an end to turn it into a story. People miss that basic step. That’s the first part.

The second is that they underestimate the audience. They think because it’s for young children, you have to use very simplistic ideas. But they’re young, not stupid, right? They’re just like us, only younger. I always say that with my nonfiction, I don’t simplify it, I clarify it. It’s different. You know, it’s very complex stuff that you have to figure out how to explain. You can use big words, but you have to know how to use them. Don’t underestimate the audience.

And the third is that the main character for most picture books is usually a small child, or a small animal stand-in for a child. A lot of what I see from amateurs is what we call the Grandma Book, where, you know, grandma loves to golf, right? So, Grandma wrote a book about herself. She thinks it’s good because her granddaughter loves to read it with her, but that’s because she’s sitting on your lap, and then you go have cookies, right? It’s not because the story’s great. So, the ability to get into the head of the child and write from their point of view–FOR their point of view–that’s important.

RVC: Gotcha. Thanks for that!

HB: That’s three things. Do you want one more?

RVC. At OPB, we always underpromise and overdeliver, so yes, please! Bonus time!

HJB: The page turn.

If someone buys your books, maybe they’re spending $20 on it. It’s not a lot of money, but it’s more money than zero. Compared to, say, your Netflix subscription, it can feel like a big investment. That means people want to know that they can read the book more than once. Clearly, for that $20 to be a good deal, you have to be able to read this book again and again and again. So, how are you going to hook that reader to read the book again, and again, and again? It can’t be just one joke.

With every spread and every page turn, you have to build suspense for somebody to want to turn the page and not get bored. So those are the things that I think are what I look for, in a manuscript.

RVC: How do you define success with a project or a book of yours or a manuscript?

HB: Success is an elusive thing because I think it’s different for everybody. Our society says the way a book is considered to be a success is if you sell a million copies or it’s a New York Times bestseller or they turn into a movie or you have your own stuffie–that’s as good as it gets. For me, it’s a business and I want to make money at it. I will never say, “I will do this for free!” because if you’re doing it for free, you’re not doing it well enough. Somebody is making money from your book, so you should be making money, too.

At this stage in my career–I’m like 125 years old now–I consider success to be the fact that I can actually make a living as a writer. I can keep doing it and I get to work with great people and write books that interest and appeal to me. So, yes, money is part of it. But it doesn’t have to be for everyone. If you’ve written your magnum opus and you self published it and you’re proud of it, that’s great!

RVC: You have a lot of standard talks and presentations that you regularly give. I’m going to prompt you to talk about one of those with these four words. Here goes. “No one buys poetry.”

HB: Most writers aren’t business people. We’re just not. It’s a different of part of the brain. But if you’re going to do this as a career, you need to know how to do business and what the market is. You need to choose a project that you can actually sell.

That doesn’t mean that poetry isn’t wonderful. My first book was a collection of poetry. But project selection is really important. And the problem with poetry is that you can’t translate it, or at least it’s very difficult to translate. For smaller publishers, translation rights are a huge part of their market. If you write a book of poetry, you’re cutting off any potential for them to make a lot more money that way. If you want to sell a book, maybe pick an area that has got more legs, right? Know what’s going to be able to be an easier sell, not necessarily a better book.

RVC: Rhyming books have the same problem.

HB: And it’s a shame because, of course, we all love rhyming books. A lot of my early stuff was rhyming and wordplay. Almost none of my later stuff is, though. It’s not that I like it any less. I just like to eat more.

RVC: What’s been your experience with literary agents?

HB: For most of my career, I didn’t have an agent. I sold most virtually all of my books on my own.

RVC: Wow. After all that success, what made you change and go get an agent? What was the tipping point?

HB: Someone recommended an agent to me, and it turned out to be a good fit. This was right around the time I was pitching Counting on Katherine and I’d already been talking with Christy Ottaviano, and then the agent came in. I’m really glad that I hooked up with her because she was a huge help with the contract.

RVC: We’re big fans of Christy–we did an interview with here right here at OPB. Now that we’ve bragged about that Christy O. interview, it’s your term to brag. What new projects of yours are you really excited about?

HB: Ones that are brand spanking new! Like The Fabulous Tale of Fish & Chips, which just came out in October. It tells the somewhat fanciful–but based on facts–histories of the very first fish and chip restaurant that was in London in the East End.

HB: Ones that are brand spanking new! Like The Fabulous Tale of Fish & Chips, which just came out in October. It tells the somewhat fanciful–but based on facts–histories of the very first fish and chip restaurant that was in London in the East End.

A Jewish guy came up with the idea of fish and chips. The fried fish in fish and chips is an ancient Spanish, Jewish recipe that Jews cooked in Spain on Fridays the day before the Sabbath when you weren’t supposed to cook on the Sabbath. You could eat it cold the night on the Sabbath without it tasting greasy. So, anything that’s breaded and fried started from there.

Then in 1492, because of Queen Isabella–ocean, Inquisition, all of that–all these Spanish Jews left Spain, they traveled all over the world, bringing this traditional recipe with them. Hence, you have fish and chips in England, you have fritto misto in Italy, and my favorite of all, brought by the Portuguese to Japan, tempura. They all originate from that–that was the origin of that story. The book also has my own family recipe for fried fish in it.

RVC: Congrats on that–it sounds delicious! Now, just one last question for this first part of the interview. What’s the question that no one’s ever asked you in an interview that you’ve been dying for someone to ask you?

HB: How did you manage to stay so good looking even though you’re 125 years old?

RVC: What’s the answer to that?

HB: Good genes and a youthful spirit.

RVC: Here we go, Helaine. It’s time for the SPEED ROUND!! The point values are exponentially higher, and we’re going double-time now. Are you ready?

HB: Yes!

RVC: If you had a literary mascot, what would it be?

HB: The puffin. I have a book coming out in 2023 that’s called Puffin versus Penguin, which I’m writing with Kevin Sylvester–it’s a graphic novel for younger people.

I really like puffins. And I just don’t understand why penguins get more love than puffins because puffins are better.

RVC: An underappreciated book of yours?

HB: Certainly Pirate Queen is one. It got good reviews but it came out right at the beginning of COVID. I think it’s one of my best books–the writing is lyrical and very different.

RVC: Favorite Canadian expression.

HB: “Maple Leafs suck!”

RVC: If you were going to go mini golfing as you do with four people from the picture book world who would you take?

HB: I would take my best buddies, which is my critique group. So, that’d be Frieda Wishinsky, Deborah Kerbel, Karen Krossing, and Mahtab Narsimhan, and we’d probably just throw the balls at each other then go out for drinks.

RVC: Biggest missed opportunity as a writer.

HB: What it’s like to write The Golden Compass. I missed that opportunity. Someone else got there first.

RVC: Best nonfiction picture book you read this year.

HB: The Boreal Forest by L.E Carmichael.

HB: The Boreal Forest by L.E Carmichael.

RVC: Best thing a child reader has ever said about one of your books.

HB: I have two.

Kid: Did you write this book? [pointing at The Haunted House book]

Me: Yes.

Kid: My little sister learned how to read using that book.

The only thing better than that would be having a school named after me.

And the other one was this–I’ve written a series of books for kids on dealing with stress. And they’re sort of light, but you know, they’ve got real tips in it. And one day, a kid said to me, “That book really helped me.”

RVC: Thanks for this interview, Helaine. It’s been terrific getting to know you and your work better. And the next time I’m up in Toronto, let’s go hit up a really good espresso place!