This month’s Industry Insider Interview is with Harold Underdown, a Brooklyn-based children’s book editor. His editorial experience includes being Vice President of ipicturebooks.com, editorial director of the Charlesbridge trade program, and an editor for Orchard Books and Macmillan. For a long while, he worked as a consulting/independent editor, a writing and revision teacher, a workshop/retreat leader, and an online writing teacher. As of October 2021, he started work as Executive Editor at Kane Press. That means he’s cutting back on independent editing work, though he’s still going to be teaching and leading workshops.

This month’s Industry Insider Interview is with Harold Underdown, a Brooklyn-based children’s book editor. His editorial experience includes being Vice President of ipicturebooks.com, editorial director of the Charlesbridge trade program, and an editor for Orchard Books and Macmillan. For a long while, he worked as a consulting/independent editor, a writing and revision teacher, a workshop/retreat leader, and an online writing teacher. As of October 2021, he started work as Executive Editor at Kane Press. That means he’s cutting back on independent editing work, though he’s still going to be teaching and leading workshops.

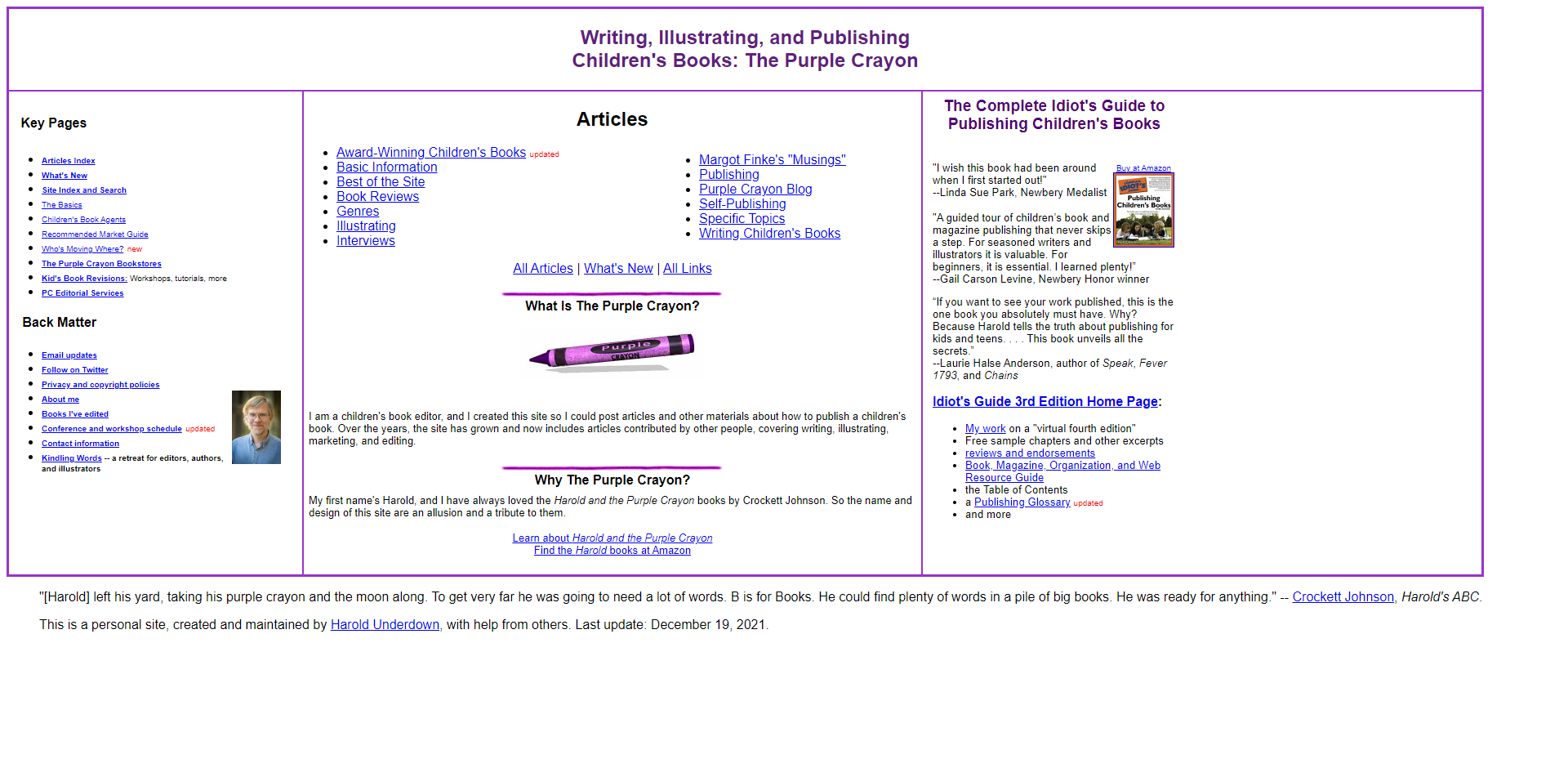

Most people in the kidlit world, however, likely know Harold best through his informative The Purple Crayon website, which was created in 1995 and remains a valuable resource for the picture book world.

To round things out introduction-wise, here are a few Harold Bio Nuggets.

Now that we know Harold a good bit better than we did 90 seconds ago, let’s get to that interview and see what he has to say about the world of picture books, discover the origin of The Purple Crayon, and find out about his cool new job!

OPB: When did you first realize you were going to be in the book industry?

HU: Unlike some people, I did not come out of college thinking, “Oh, I want to work in publishing!” In fact, for quite a long time, I thought I was going to be a teacher, which I think initially came from the fact that my dad was a university professor. But since he was a university professor, I saw the departmental politics and the requirement to publish. I didn’t want to go into that.

OPB: *laughing* Yeah. After working at seven colleges and universities, I know what you mean.

HU: After college, I went into a teaching job at a Friend’s school, and I kind of struggled with it, which led to my doing a master’s degree in education. Before that, I hadn’t had any actual training in teaching–I thought it was something you could just do.

OPB: It’s harder than most realize!

HU: I finally ended up in New York City, teaching in the public schools through an arrangement they had that was called a temporary per diem license for people who had not completed all the formal requirements, which, even though I had a master’s, I had not done. That was an interesting experience. I worked at an alternative elementary school on the Upper West Side. It was a great school. But really, I was kind of out of my depth because at that point, I still did not have enough experience or supervision. The part of it that I really liked, however, was working with the kids on reading. I read out loud to them. And they loved it.

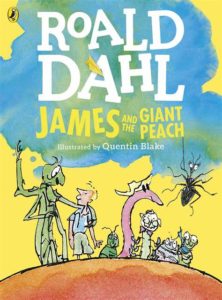

This was a mixed group of third and fourth graders. I still remember reading James and the Giant Peach to this group of New York City kids. Since I had English family on my father’s side, I was able to do different British accents for the insects, and they loved that. That taught me something: here’s this book that’s mostly set in England and these kids from New York City were totally into it.

This was a mixed group of third and fourth graders. I still remember reading James and the Giant Peach to this group of New York City kids. Since I had English family on my father’s side, I was able to do different British accents for the insects, and they loved that. That taught me something: here’s this book that’s mostly set in England and these kids from New York City were totally into it.

I taught a very diverse group of kids, yet I couldn’t find books in which they could see themselves and I was definitely looking for that. There were a few, but there weren’t nearly as many as there are now. And I thought, okay, so maybe if I’m not going to be teaching, maybe I can go into publishing and help create more books for kids like the ones I’m teaching. And that was actually what ended up happening.

OPB: How’d you go from that goal to landing that first publishing job?

HU: I did the typical pre-Internet job-hunting things. What ended up working was that my stepmother’s mother used to work at Greenwillow and still had some publishing connections. I sent my resume to someone she knew who was working at Macmillan–this being the old Macmillan–and she passed it along.

From that, I got started as an editorial assistant.

OPB: What was the first picture book that you worked on by yourself?

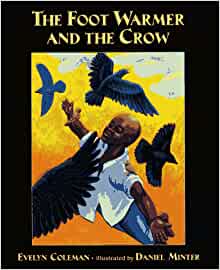

HU: Well, I wouldn’t say I worked on it completely by myself, but the first picture book that I regard as a book that I was deeply interested in and really wanted to acquire and bring on was The Foot Warmer and the Crow by Evelyn Coleman. It tells the story of an enslaved man who escapes from slavery with the help of a crow. It’s a folktale-like story–very, very powerful. And I wanted to find some appropriate art to go with it–a picture book illustrator who could really carry the story.

HU: Well, I wouldn’t say I worked on it completely by myself, but the first picture book that I regard as a book that I was deeply interested in and really wanted to acquire and bring on was The Foot Warmer and the Crow by Evelyn Coleman. It tells the story of an enslaved man who escapes from slavery with the help of a crow. It’s a folktale-like story–very, very powerful. And I wanted to find some appropriate art to go with it–a picture book illustrator who could really carry the story.

I looked through the art files and I talked to our art director. We eventually came up with someone who I thought was a good possibility. I told Evelyn about it and showed her samples. She wasn’t crazy about this guy. And she said, “Well, there’s this artist here in Atlanta. Can I send you some pictures of his art? I think he should be the illustrator.” Of course, I said the usual thing, “You know, we REALLY know what we’re doing here. It’s up to us to choose the artists…but if you want to, you can send the art to me.” And so she sent me a whole package of samples by Daniel Minter. At the time, he was a fine artist doing sculptures.

I looked at the samples and said, “Oh, yes. This is exactly what we need.” And fortunately, Daniel was open to the idea of illustrating a picture book.

OPB: I don’t know this book well, I’m afraid. It came out in the early 1990s–well after I stopped reading picture books as a kid, and not yet where I was reading them again as an adult. How was the book received when it came out?

HU: The book itself turned out really well. I think in some ways, it was a book that was ahead of its time. It didn’t stay on the market long. But it led to Daniel Minter becoming a children’s book illustrator, so that was a good thing.

OPB: Agreed. His art has received a Caldecott Honor, and with good reason. Now, let’s get back to you. In speaking with so many industry folks over the years, it seems to me that the picture book world does a very good job letting new agents and editors learn in an apprenticeship model. Was that how it worked for you?

HU: That’s an interesting question. And I actually would say that I didn’t have a full on apprenticeship kind of situation. Because I was working for Macmillan Children’s Books–a large, general purpose children’s book imprint–we did everything from picture books up to young adult. We even had the Macmillan Dictionary for Children along with a couple of other reference books.

HU: That’s an interesting question. And I actually would say that I didn’t have a full on apprenticeship kind of situation. Because I was working for Macmillan Children’s Books–a large, general purpose children’s book imprint–we did everything from picture books up to young adult. We even had the Macmillan Dictionary for Children along with a couple of other reference books.

There were three or four editors within the imprint–Judith Whipple, Beverly Reingold, and my boss Neal Porter, who was the publisher. I was officially working for Neal, but I also interacted with everybody else, so I was actually learning from all of them. One of the things they did within the department was make copies of all their important correspondence and put it in a file. That would get circulated weekly so we could all see what everybody was working on. That was always really interesting for me to read, because I could see how an editor wrote an editorial letter and how they corresponded with an artist. Another lesson I learned was the reality that publishing is a business.

OPB: That’s a tough realization, isn’t it?

HU: I thought of publishing as this noble calling where people are simply making wonderful books. And it is! But also, for every single book that we acquired, I had to do a P&L [profit and loss statement]. And it had to work out and make money for us, after I put in all the expenditures and an overhead percentage and so on. It had to hit a target number of profit.

OPB: You were a freelance editor for a long time. What were the benefits and challenges of moving away from working with publishing houses?

HU: I didn’t really get out of it. Because even when I was not working at a trade house, I was still very involved with the industry through my freelance work and the workshops that I did. All along, my intention was to get back there. What happened instead was that I ended up going off on a very long tangent.

OPB: Do tell!

HU: I had been working at Charlesbridge, which was a great place to work–a very good company. I was essentially commuting from New York City to Boston. My wife and I wanted to have a baby. We both agreed that we couldn’t do that if I was in Boston half the time. So, I looked for jobs back in New York. Unfortunately for me, the one that I got was working for a book packager. This was 2000 or so, and the owner was trying to set up a children’s focused ebook company. There were two problems with this. One of them was that it was way early to do a children’s ebook company. This was several years before the Kindle format came along. Nobody had figured out how to how to sell ebooks. Consumers didn’t want ebooks. There was probably some kind of market there–in the library market–but the owner wasn’t interested in that. So, we were going after a market that didn’t exist.

The second problem was the owner ran his own business badly, and treated his staff badly. Fortunately, this didn’t last long because he ran out of funds. He had some seed capital from Time Warner but he blew through it in a year and a half.

Honestly, it was a terrible experience in some ways. Yet I learned things from that, for sure, like the importance of finding out what the culture of the place is like before you take a new job. I’ll never do that again!

OPB: I hear you there! Culture matters. What happened next?

HU: I needed to find something quickly to support us. This was now the down slope of the .com years, so there wasn’t a lot of hiring going on. I consider myself lucky to have gotten a job at McGraw-Hill then. My teaching background was something they were looking for, along with my editorial background. I worked there on and off until fairly recently.

If you know anything about educational publishing, this fact will not surprise you–while I was at McGraw-Hill, they went through four rounds of layoffs. For someone who had worked in trade publishing, it was hard to understand what the problem was, but I think part of it was that they did textbook publishing, and that’s a business in which there’s enough money involved that they could afford to hire expensive consultants. And each time, the expensive consultants would tell them to do some something else to fix the company. Unfortunately, one of the things that was always involved was laying off people.

The last time this happened, I was one of the people who got laid off.

OPB: I’ve written textbooks, and I’ve seen the carousal of editors in educational publishing firsthand. You’re exactly correct.

HU: It wasn’t the end of the world. I had freelance work, which I’d been doing on the side, so I had connections to build up. But I also knew this was the time to get back into trade publishing. I had looked into doing that even while I was at McGraw-Hill, and I had talked to people about it, but I never found the right position for me, given my experiences and abilities. So I got very serious about hunting in a way I hadn’t before, and the Kane Press job came along.

OPB: When did that happen?

HU: Last summer. I’d had Kane on my radar because Bobbie Combs, who I know from working at the Highlights Foundation, had introduced me to Juliana Lauletta, who’s their publisher. So, I knew a little bit about them. Kane Press is interesting, because Joanne Kane, who founded Kane Press about 30 years ago, started the press very deliberately wanting to publish books that had an educational component. But the books weren’t textbooks. She was aiming at a very specific market, and that’s what she did as an independent publisher for quite a long time.

Kane was the first company that Thinkingdom Media Group acquired when they moved into the US market. As you probably heard, they also bought Boyds Mills, Calkins Creek, and Wordsong. And they made a deal to buy minedition, a picture book company started by Michael Neugebauer, who’s a very well-known Swiss publisher and a picture book specialist. He had worked at North South Books, and then he went out on his own and started minedition. And he decided to sell it to what became Astra. This year, they also brought Jill Davis in, who started Hippo Park as her personal imprint. So, they essentially assembled a publishing house, with an adult imprint and a literary magazine as well. And in 2020, they set up Astra Publishing House.

At that point, they wanted to bring somebody else in at Kane Press to help build it up and, hopefully, take it in a few new directions. Basically, that’s what I’m aiming to do.

OPB: Why was Kane Press the right fit for you?

HU: It was the right match for me because the things that I want to build out are very much things that they were already thinking about. For example, Kane Press has always done series publishing, like Math Matters and Science Solves It! More recently, there’s the Eureka! The Biography of an Idea series. All of these were developed in house and they would then hire authors and illustrators to create individual titles.

We’re going to continue to do that. But I made the point right at the beginning that while we may be brilliant, there are only so many ideas we can have. What if we open up the doors to proposals from the outside and see what people offer us?

That’s essentially been my main focus in the first two months–writing out how that would work, developing guidelines, and letting people know that we’re open. We’ve pretty narrowly defined it because we don’t just want to get lots of random submissions. We want to get series proposals with a sample manuscript and there are certain things we look for in them. We’re being cautious and we’re only looking at these if they’re from published authors, or from an agent.

OPB: Let’s help out some writers and agents here. In your capacity as Executive Editor at Kane Press, what ARE you looking for?

HU: One of the things people need to do before they do anything else is familiarize themselves with some of the books that Kane has published and try to get a feel for what distinguishes it from other companies. Because one of the things I’ve noticed already is people think, “Kane is educational, so they must be publishing those library series like Lerner and Capstone do.” And that’s what writers send us.

That’s not what we publish.

Also, almost all of our books are illustrated rather than photo illustrated. In fact, we did a photo series long before I arrived here. It was kind of a disaster.

The series that they’ve succeeded with have been ones that somehow walk a line between the school and library market, but they also speak to parents, maybe parents who are homeschooling or maybe parents who are just looking for something that’s going to supplement what kids are getting in school.

OPB: So they’re going to have a trade feel to them?

HU: Before I arrived, they’ve already been upgrading their illustration style and moving in a direction that makes the books look more like something you would see on the shelf in a bookstore. To me, the goal is that we’re going to publish books that are going to be every bit Kane Press books in the sense that there’s an educational component, either in the story, or, for nonfiction, in the facts. It’s got to have really great back matter, too, which is something Kane Press has a name for.

OPB: Let’s circle back to your website, The Purple Crayon. That’s how a lot of people know you, I think. Why did you start that? And what has it done for you over the years?

HU: The Purple Crayon goes back to 1995. Believe it or not, it was something that I started in between working at Orchard Books and Charlesbridge. When I moved to Orchard with Neal Porter, I got caught up in a kind of messy situation. Orchard Books–which at the time was owned by Grolier, which was primarily a reference publishing company–didn’t know how to deal with this sort of high-end trade children’s imprint that they somehow had. I’m still not entirely sure how they actually owned it. They didn’t know how to deal with it, and so people were unhappy there. And this was Neal Porter, Dick Jackson, and Melanie Kroupa. Three pretty amazing editing people.

HU: The Purple Crayon goes back to 1995. Believe it or not, it was something that I started in between working at Orchard Books and Charlesbridge. When I moved to Orchard with Neal Porter, I got caught up in a kind of messy situation. Orchard Books–which at the time was owned by Grolier, which was primarily a reference publishing company–didn’t know how to deal with this sort of high-end trade children’s imprint that they somehow had. I’m still not entirely sure how they actually owned it. They didn’t know how to deal with it, and so people were unhappy there. And this was Neal Porter, Dick Jackson, and Melanie Kroupa. Three pretty amazing editing people.

We happened to be in the same office building on Madison Avenue with Dorling Kindersley and we would be going up and down in the elevator with Dorling Kindersley people. Neal in particular got talking to them, and it led to the three of them leaving and starting a new imprint at Dorling Kindersley that didn’t last long, but it got them out of the Grolier situation. I ended up getting laid off. So, while I was looking around for the next thing–which turned out to be Charlesbridge–my brother told me about this thing he discovered called the World Wide Web.

I had already been going to SCBWI conferences and the like, and giving presentations. I had one called Getting Out of the Slush Pile that was based on my experience as an editorial assistant and a young editor, being the person who read all the manuscripts that came in that nobody else wanted to read. This was back in the day when publishers hadn’t closed the doors to open submissions yet.

I thought I could put this presentation up on the web, and then people could find it from all over the world. And so I did that. The website initially was that and a couple other articles that I’d written. I think I pretty early on started the Who’s Moving Where page, which is a sort of chronological listing of editors who’ve moved around, or new imprints that have been started. And I just update that whenever I can, which isn’t very often these days.

OPB: The industry can move pretty fast sometimes. I feel your pain there.

HU: In terms of what’s on the website, some parts of it, honestly, I haven’t paid any attention to for years, but I try to keep up. The key informational articles and the Who’s Moving Where page, though, I try to keep up to date.

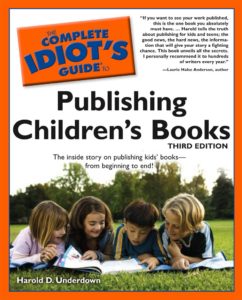

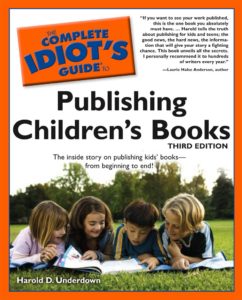

Having that website kind of increased my visibility. Definitely, it’s led to conference opportunities and things like that. And also interestingly enough, that led directly to The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Publishing Children’s Books.

Having that website kind of increased my visibility. Definitely, it’s led to conference opportunities and things like that. And also interestingly enough, that led directly to The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Publishing Children’s Books.

OPB: How was it making that book?

HU: This is back in like 2000/2001. The Complete Idiots series had this model where they would publish one in a particular area, and in this case, it was just publishing in general. If it was successful, then they’d look for ways to kind of subdivide it. So they thought, we’ve got a successful The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Getting Published. Now, we should do children’s books and romance novels, and I don’t know what else they did, but I was not the only subdivided idea they had.

They would go out and look for experts and essentially commissioned those people to write them. And they found me through The Purple Crayon. Writing for them was an interesting experience. They had you write a very detailed outline, down to the subheads of the entire book. I think it ended up being about 10 pages long and and then you just kind of crank that out. One of the good things about that kind of structure is it’s very flexible. They let me say the things I wanted to say.

We were able to update it a couple of times since then. Unfortunately, they’ve sort of shifted their model, and they’ve stopped doing revised editions–they only do new titles. So the current edition that’s out in the market is about 10 years old.

Most of it’s still still pretty solid. I wish I could update it again.

OPB: I have to ask–what’s your editing superpower?

HU: That’s a great question. I think that this applies both to a freelance situation and to in-house work. I try to understand what an author is trying to do themselves, where are they going with this story or this piece of nonfiction. I try to get inside of it and see what’s working, what isn’t working. I try not to impose my ideas about what they should do but instead help them build it in the direction that they’re already trying to go. To me, that’s the best kind of editing.

Now, I don’t necessarily do that all the time. There are times when, for market reasons or practical reasons, I may say, “We need to do X, Y, and Z.” Or “This is too long.” That’s not editing from inside of the story, though.

What I always try to do is to get into the story to really take it in and understand where the writer’s going with it, and help them do it better.

OPB: One last question for this part of the interview. What are Harold Underdown’s feelings about art notes?

HU: I talk about this regularly because I teach the Crash Course in Children’s Publishing: Everything You Need to Know at the Highlights Foundation, which is probably the only course like that anywhere. In it, we focus on the practical and the business side of publishing and how that all works. So, it’s not a writing or illustrating craft course. We get a lot of people who are what I would call serious beginners. They’ve gotten into the field and are probably writing, but they just don’t understand how things work and they want to find out.

And art notes always come up.

I will say my thinking on art notes has evolved. Back in the day, I would always say–and this used to be the standard thing people said–“Don’t put in art notes. Don’t tell the illustrator what to do.”

I’m not as absolute now. The big thing I warn people about–I see people doing this a lot in manuscripts that I’ve been given a conferences, or the stuff that my students show in workshops–is using art notes as a substitute for the story that you want to tell. If you’re doing, that you’re not using art notes correctly. You should only be using art notes when it’s absolutely necessary to tell the illustrator something they won’t figure out simply by reading the entire manuscript.

OPB: Okay, Harold. It’s time for the Speed Round. Fast questions and faster answers, please. Are you ready?

HU: All set!

OPB: What’s the best place for REAL New York City pizza?

HU: There are a lot of options here, but I’m just going to mention one in my immediate neighborhood: Graziella’s Pizza on Vanderbilt Avenue.

OPB: “If I could be any picture book character for a day, it’d be ____________.”

HU: Harold from Harold and the Purple Crayon, of course. What’s great about him is that he never stops trying. He gets into trouble, and he draws his way out of it. He’s very creative.

HU: Harold from Harold and the Purple Crayon, of course. What’s great about him is that he never stops trying. He gets into trouble, and he draws his way out of it. He’s very creative.

OPB: What’s a secret vice?

HU: I picked up a fascination with cricket from my English father, and I still follow it. I like the international politics of the sport, which are fascinating. If you’re a soccer fan, for example, you know how corrupt FIFA is, right? There’s similar stuff in cricket, though, perhaps not as quite as pervasive.

OPB: Biggest time waster?

HU: Facebook and Twitter.

OPB: Your picture book philosophy in five words or less.

HU: Picture books are for children.

OPB: Thanks so much, Harold. This was truly informative! Best of luck at Kane Press.

Barbara Throws a Wobbler by Nadia Shireen (1 June 2021)

Barbara Throws a Wobbler by Nadia Shireen (1 June 2021) Don’t Hug Doug (He Doesn’t Like It) by Carrie Finison, illustrated by Daniel Wiseman (26 January 2021)

Don’t Hug Doug (He Doesn’t Like It) by Carrie Finison, illustrated by Daniel Wiseman (26 January 2021) Eyes That Kiss in the Corners by Joanna Ho, illustrated by Dung Ho (5 January 2021)

Eyes That Kiss in the Corners by Joanna Ho, illustrated by Dung Ho (5 January 2021) I Am Not a Penguin: A Pangolin’s Lament by Liz Wong (19 January 2021)

I Am Not a Penguin: A Pangolin’s Lament by Liz Wong (19 January 2021) King of Ragtime: The Story of Scott Joplin by Stephen Costanza (24 August 2021)

King of Ragtime: The Story of Scott Joplin by Stephen Costanza (24 August 2021) The Longest Storm by Dan Yaccarino (21 August 2021)

The Longest Storm by Dan Yaccarino (21 August 2021) The Midnight Fair by Gideon Sterer, illustrated by Mariachiara Di Giorgio (2 February 2021)

The Midnight Fair by Gideon Sterer, illustrated by Mariachiara Di Giorgio (2 February 2021) Milo Imagines the World by Matt de la Peña, illustrated by Christopher Robinson (2 February 2021)

Milo Imagines the World by Matt de la Peña, illustrated by Christopher Robinson (2 February 2021) My First Day by Phùng Nguyên Quang and Huy’nh Kim Liên (16 February 2021)

My First Day by Phùng Nguyên Quang and Huy’nh Kim Liên (16 February 2021) Off to See the Sea by Nikki Grimes, illustrated by Elizabeth Zunon (12 January 2021)

Off to See the Sea by Nikki Grimes, illustrated by Elizabeth Zunon (12 January 2021) Outside, Inside by LeUyen Pham (5 January 2021)

Outside, Inside by LeUyen Pham (5 January 2021) The Rock from the Sky by Jon Klassen (21 April 2021)

The Rock from the Sky by Jon Klassen (21 April 2021) A Sky-Blue Bench by Bahram Rahman, illustrated by Peggy Collins (30 November 2021)

A Sky-Blue Bench by Bahram Rahman, illustrated by Peggy Collins (30 November 2021) Something’s Wrong!: A Bear, a Hare, and Some Underwear by Jory John, illustrated by Erin Kraan (23 March 2021)

Something’s Wrong!: A Bear, a Hare, and Some Underwear by Jory John, illustrated by Erin Kraan (23 March 2021) Ten Beautiful Things by Molly Beth Griffin, illustrated by Maribel Lechuga (12 January 2021)

Ten Beautiful Things by Molly Beth Griffin, illustrated by Maribel Lechuga (12 January 2021) Tomatoes for Neela by Padma Lakshmi, illustrated by Juana Martinez-Neal (31 August 2021)

Tomatoes for Neela by Padma Lakshmi, illustrated by Juana Martinez-Neal (31 August 2021) Two Grooms on a Cake: The Story of America’s First Gay Wedding by Rob Sanders, illustrated by Robbie Cathro (4 May 2021)

Two Grooms on a Cake: The Story of America’s First Gay Wedding by Rob Sanders, illustrated by Robbie Cathro (4 May 2021) Unspeakable: The Tulsa Race Massacre by Carole Boston Weatherford, illustrated by Floyd Cooper (1 February 2021)

Unspeakable: The Tulsa Race Massacre by Carole Boston Weatherford, illustrated by Floyd Cooper (1 February 2021) Watercress by Andrea Wang, illustrated by Jason Chin (30 March 2021)

Watercress by Andrea Wang, illustrated by Jason Chin (30 March 2021) We All Play by Julie Flett (25 May 2021)

We All Play by Julie Flett (25 May 2021) Weirdo by Zadie Smith and Nick Laird, illustrated by Magenta Fox (15 April 2021)

Weirdo by Zadie Smith and Nick Laird, illustrated by Magenta Fox (15 April 2021)

This month’s Industry Insider Interview is with Harold Underdown, a Brooklyn-based children’s book editor. His editorial experience includes being Vice President of ipicturebooks.com, editorial director of the Charlesbridge trade program, and an editor for Orchard Books and Macmillan. For a long while, he worked as a consulting/independent editor, a writing and revision teacher, a workshop/retreat leader, and an online writing teacher. As of October 2021, he started work as Executive Editor at Kane Press. That means he’s cutting back on independent editing work, though he’s still going to be teaching and leading workshops.

This month’s Industry Insider Interview is with Harold Underdown, a Brooklyn-based children’s book editor. His editorial experience includes being Vice President of ipicturebooks.com, editorial director of the Charlesbridge trade program, and an editor for Orchard Books and Macmillan. For a long while, he worked as a consulting/independent editor, a writing and revision teacher, a workshop/retreat leader, and an online writing teacher. As of October 2021, he started work as Executive Editor at Kane Press. That means he’s cutting back on independent editing work, though he’s still going to be teaching and leading workshops.

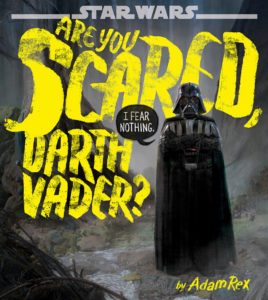

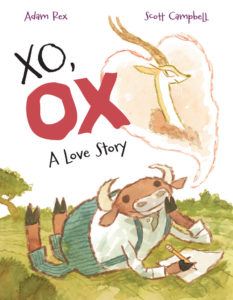

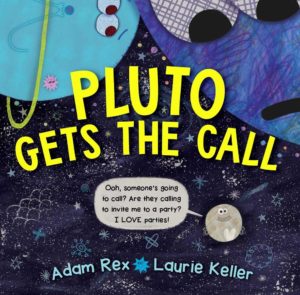

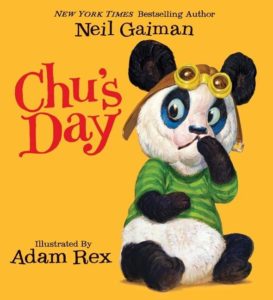

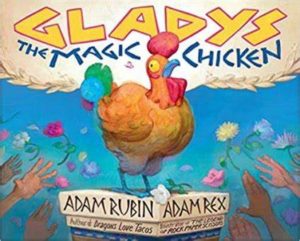

We always like to end the year strong, and thanks to December’s guest author interview, we’re doing exactly that. Welcome to Only Picture Books, Adam Rex!

We always like to end the year strong, and thanks to December’s guest author interview, we’re doing exactly that. Welcome to Only Picture Books, Adam Rex!