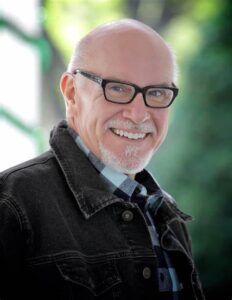

Welcome back to Rob Sanders, the first person we’ve asked to come back for a second interview. He was the first-ever Author Interview when we launched OPB exactly six years ago, and his career has taken off in a way that makes asking him for a follow-up interview a no-brainer.

Welcome back to Rob Sanders, the first person we’ve asked to come back for a second interview. He was the first-ever Author Interview when we launched OPB exactly six years ago, and his career has taken off in a way that makes asking him for a follow-up interview a no-brainer.

Now, if you want to know about Rob’s past, hit up that other interview. This one’s going to dig into all Rob’s been up to lately, what’s he doing now, and what’s coming up later. Plus, we’ll tackle some bigger aspects of the industry because Rob’s the right person to offer real insight.

Let’s get right to it, then!

RVC: Since our last interview (April 2018), how has your approach to storytelling evolved? What do you know/do now that you didn’t know/do then?

RS: Probably the only way I can answer that question is to say I’ve stayed open to possibilities. Since 2018, I’ve written books (or had books acquired) that are fiction and nonfiction picture books, worked in collaboration with another author on two nonfiction biographies, published my first historical fiction middle grade novel in verse, and have a book of poetry releasing this year. Many authors have a “writing lane” in which they are marvelously successful. That model just doesn’t work for me. I guess I’m a drive-all-over-the-road kind of writer. I like variety. I like finding unique approaches to stories. I like finding the one best way for me to tell a story.

The more I write and the more I’m published, the more I know how much I don’t know. Authors I teach and critique often want me to tell them which of their manuscripts will be the most successful, which will be the right one to submit, which will get published. Golly-gee-willikers, I don’t know. No one does. The industry is far too subjective for that kind of prediction. (And if I did have that kind of crystal ball, I wouldn’t experience rejections myself, would I?)

Every story is one “yes” away from being published. Writing takes perseverance, tenacity, and a pretty thick skin. But to answer the question … since 2018, I think I’ve become braver. Braver in my selection of topics. Brave enough to stand up for and represent my work to others. Brave enough to take risks.

RVC: I get your drive-all-over-the-road kind of writer approach because it’s what I do, too. But one of the challenges I’ve faced as a result of that is that branding becomes more of a challenge.

RS: Honestly, Ryan, I spend very little time thinking about platform, brand, and the like. Maybe I should be thinking about that, but I don’t. What do I do? I think of my published work as my brand. In query letters, my agency always includes something like “Rob Sanders, a pioneer in LGBTQIA+ nonfiction and the author of …” which firmly establishes or reestablishes me in the mind of an editor. I keep a list of reviews, honors, and awards for all my titles and have them available for publishers who request that.

Years ago, I had a wonderful website built and over time, my designer helped make it everything I envisioned and more. I send updates to my designer once or twice a year and/or when there’s new information (a review, award, new book, etc.) to share. I have a presence on Facebook and Instagram (I recently gave up Twitter/X) and I grow my reputation further by judging writing contests; teaching classes; serving as a mentor for various organizations; writing for blogs, newspapers, etc.; critiquing; and more. I feel that my time is best spent when I’m creating and focusing on my writing and when I’m helping others on their creative journeys.

RVC: How do you specifically navigate the challenge of writing for a dual audience—engaging both children and the adults who read to them (and who most often buy the books)?

RS: Can I say golly-gee-willikers again or is this a family show?

RVC: We’re a hearty bunch. We can take it!

RS: How do I write for two audiences? Well, I don’t.

RVC: Interesting. What do you do then?

RS: I find the best way into a story, the best way to “package” it or tell it and I write the best story I can. I stay open to input from others and revise my pants off and then I work with my agent to find the best editorial/publishing fit for each manuscript. Truthfully, that match takes a bit of serendipity or a bit of luck. But when an editor makes an emotional connection to a story, they will become that story’s champion to others on the acquisition team. When that acquisition team begins to feel the same passion for a story, they will represent it positively to their sales staff who will represent it positively to book buyers who represent it to customers. Ultimately, a well-written children’s book will attract adults—the purchasers—precisely because they know or feel that kid readers will make a connection with the book—just like that acquiring editor did.

RVC: You brought up three intriguing ideas there, and I want to talk about each in greater depth. The first one is the idea of revising your pants off. What does the revision process look like for you?

RS: Each project presents its own revision demands. Of course, we all begin by looking at word choice, story arc, character development, and the like. But there are other things that may be even more important. To me entry point, structure, and presentation are huge. By entry point I mean that “thing” that helps pull a kid into a story, gets them to keep reading, and what they relate to in the story. Structure refers to how the story is told, built, sequenced, and so on. And presentation—probably a sibling of structure—is how the manuscript actually appears on the page. I can give you an example …

RVC: Please do!

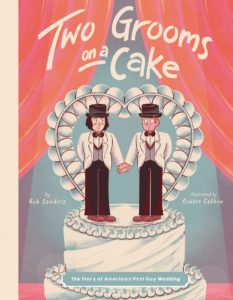

RS: When I was writing about the first legal gay marriage in the US, the story of Michael McConnel and Jack Baker was compelling to me. There were twists and turns, legal battles, court cases, intrigue, and a wedding. I wrote the first few drafts recounting those events. But each draft seemed to lack kid appeal. I kept asking myself, “Why would a kid care about this?”

RS: When I was writing about the first legal gay marriage in the US, the story of Michael McConnel and Jack Baker was compelling to me. There were twists and turns, legal battles, court cases, intrigue, and a wedding. I wrote the first few drafts recounting those events. But each draft seemed to lack kid appeal. I kept asking myself, “Why would a kid care about this?”

So, I started to think about what I enjoyed most about the many weddings I attended as a kid. And the obvious answer was—cake. I decided that the wedding cake (prominently featured in the photos from Michael and Jack’s wedding) had to be included in the story. The cake became the entry point. But how would I tell the story, how would it be structured? I decided that parallel narratives—one that told the story of how a cake is made and the other telling the story of how a relationship is formed—would be my structure. To present that on the page I literally wrote the cake’s story flush left and indented three or four times over whenever I was telling the relationship story. Throughout the manuscript the typed page presented that back-and-forth story telling which gave a visual clue to my agent and potential editors about how the story could be shown in a book.

This is a nonfiction example, but the same three things—entry point, structure, and presentation—apply to my revision of fiction, too.

RVC: What do you think is the most common misconception writers have about revision?

RS: I think most of us writers fall into one of two revision camps—the this-is-too-hard camp and the that’s‑good-enough camp. Most writers stop revision too soon because of the difficult nature of what they’re facing or because they’re content with the progress they’ve made. We have to fight our way through those two roadblocks to really dig into revision successfully. Beyond that, I think many writers feel revision is completed once a manuscript is acquired. Oh, no, my friend, it’s just begun. Even the “simplest” of picture books, a concept book, or a wordless picture book may have multiple revision notes from an editor. And there may be multiple rounds of revisions. The two ways to be successful at this level of revision are to be professional and to meet deadlines.

Being professional includes taking the comments to heart, revising the best that you can, and noting for the editor any revision comment with which you don’t agree and explaining why. At this stage, revision really becomes a conversation (usually on paper) between the editor and the writer. My goal with revision deadlines is to return my work well before a stated deadline. That’s the kind of thing editors appreciate and remember.

RVC: You also said you “work with my agent to find the best editorial/publishing fit for each manuscript.” What’s your role in that? I think some people assume that they only need to hand a manuscript to an agent, and then they can/should wipe their hands clean of it. It’s all on the agent now. “Go make the publishing magic happen, Agent! Make the royalty checks rain!”

Are you regularly discussing publishing houses and editors with your agent? Are you checking the Rob Sanders submission database and strategizing?

RS: Regularly, no. As needed, yes. Because I attend live and virtual writing events and am often on faculty for events, I meet lots of editors and hear them speak. Sometimes I’ll hear an editor say something that prompts me to think that one of my manuscripts might be a fit for them. I let my agent know that right away. When I’m at a convention wandering through the booths of various publishing companies, I pay attention to the books on display. I introduce myself and chat up the folks in the booth and hear them talk about their books. If I feel that my work might fit with that publisher’s goals or aesthetic, I remember to let my agent know. Or I might text my agent right then and there asking, “What do you know about Publisher B and Publisher T? They have some great work on display.” When my agent is ready to send something out on submission, we look at the proposed submission list together. I might suggest an editor or two to add to the list, or editors that we might send to if we have a round two of submissions, and I might even suggest someone on the list be removed. I don’t demand anything from my agent. We discuss things and come to an agreement. Sometimes my suggestions pay off. (Of course, sometimes they don’t! LOL!)

RVC: Another topic you mentioned above is about readers (including editors) and making an emotional connection with them. Clearly, an obvious way to do that is to have a topic that’s inherently emotional, such as your fine book, Stonewall, A Building, an Uprising, a Revolution. But I get the sense that you do more than simply choose a topic that’s inherently emotional. What kind of specific things do you do in terms of creativity and craft to create or heighten the emotional impact of a picture book story?

RVC: Another topic you mentioned above is about readers (including editors) and making an emotional connection with them. Clearly, an obvious way to do that is to have a topic that’s inherently emotional, such as your fine book, Stonewall, A Building, an Uprising, a Revolution. But I get the sense that you do more than simply choose a topic that’s inherently emotional. What kind of specific things do you do in terms of creativity and craft to create or heighten the emotional impact of a picture book story?

RS: We all wonder what makes an editor or an acquisition team say, “Yes!” to a manuscript. Undoubtedly, there are many answers to that question, but I don’t think an emotional topic alone is the answer. To me, the main reason an editor and/or acquisition team says, “Yes!” is because they feel something when they read a manuscript. An emotional connection is made. Wiley Blevins from Reycraft once said that every editor on the Reycraft team had to emotionally connect with a manuscript for the company to make an offer to acquire. In other companies, you may just need to make that connection with the acquiring editor who will then champion the book to others in the company.

Many people at Random House have told me a story about Michael Joosten, who was my editor for Pride and Stonewall. When Michael pitched Pride to the folks at his company he welled up and began to cry. Michael was so convinced of the need for that book and so related to its content that his emotional connection came pouring out. His connection helped others connect and be enthusiastic about the book, too.

Many people at Random House have told me a story about Michael Joosten, who was my editor for Pride and Stonewall. When Michael pitched Pride to the folks at his company he welled up and began to cry. Michael was so convinced of the need for that book and so related to its content that his emotional connection came pouring out. His connection helped others connect and be enthusiastic about the book, too.

Of course, the emotional connection doesn’t have to be tears. It might be belly laughs; a warm, fuzzy feeling; a stirring of memories; or a million other things. Robert Frost is credited with saying, “No tears in the writer, no tears in the reader. No surprise in the writer, no surprise in the reader.” Your own emotional connection to the story is a hint that others may connect with it, too. If you don’t feel that emotional connection, then others may not feel it either.

RVC: Let’s circle back to you and how you operate. Some writers fuel their creative efforts with constant reading, but others insist that they must put aside books when the muse strikes. Where’s the intersection of creativity and reading for you?

RS: They say the first step to healing is admitting you have a problem, so here goes: I’m a picture book-aholic. I’m constantly reading new books, dipping back into favorite books, ordering books that I hear others talk about, etc. And I always have writing projects going on. So, creativity and reading are smashed together for me. I have to feed my creative muse and I do that by reading, going to museums, spending time at the beach, seeing plays and musicals, and more. For me creativity and reading go hand in hand. I’ll be quick to add that one size does not fit all. Each of us has to find what works for us and then work it!

RVC: What books are on your nightstand right now?

RS: I don’t have a nightstand, but I have books to read piled up in my office, on my dresser, in a chair in the living room, and in the bathroom. (And that doesn’t include books that are in research stacks.) I pulled one book from each of the four stacks mentioned above and here’s what I found:

Your Guide to Not Getting Murdered in a Quaint English Village by Maureen Johnson and Jay Cooper

Your Guide to Not Getting Murdered in a Quaint English Village by Maureen Johnson and Jay Cooper

Reimaging Your Nonfiction Picture Book: A Step-by-Step Revision Guide by Kirsten W. Larson

Desert Queen by Jyoti Rajan Gopal

Farmhouse by Sophie Blackall

RVC: What question are you asked most frequently about your writing career?

RS: I’m frequently asked about my nonfiction: “Why do you write controversial books?”

RVC: What’s the answer?

RS: I don’t write controversial books. I write about history. History is not controversial. But not teaching history is controversial.

RVC: Here’s the last question for this part of the interview, Rob. What’s on tap for you next? What upcoming things are you most excited about?

RS: I have three books slated for release this year and three more next year. Coming this year are:

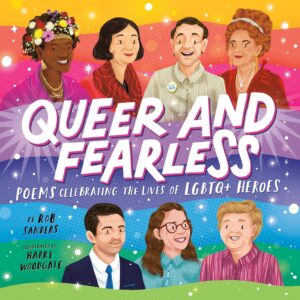

Queer and Fearless: Poems Celebrating the Lives of LGBTQ+ Heroes

April 2024

Illustrator: Harry Woodgate

Publisher: Penguin Workshop

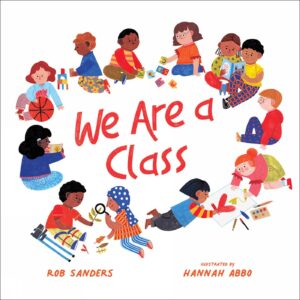

We Are a Class!

July 2024

Illustrator: Hannah Abbo

Publisher: Beaming Books

Between You and Me

December 2024

Illustrator: Raissa Figueroa

Publisher: HarperCollins

RVC: Alrighty now…it’s time to sound the alarm, buckle your literary seatbelts, and batten the hatches because we’re going to plunge straight into the high-stress depths of THE LIGHTNING ROUND!!! Six questions followed by six answers in zippy-skippy fashion, please.

Rob…are you prepared for the electrifying challenge?

RS: Bring it on!

RVC: What outdated slang do you use on a regular basis?

RS: Coolio.

RVC: What’s the most interesting or unusual talent you have?

RS: I don’t know if I can still do it, but I used to be able to twirl a baton.

RVC: If you could sip lemonade on the porch all afternoon with three kidlit creators, who would it be?

RS: Jane Yolen, Tomie dePaola, and Maurice Sendak. (I’m pretty sure they all knew one another so it would be a lively time.)

RVC: Who’s a nonfiction picture book writer you want everyone to read?

RS: Barb Rosenstock.

RVC: Who sets the standard for funny picture book rhymes?

_jfif.jpg) RS: I have to name two people—I love the humor of Tammi Sauer and the rhyming of Lisa Wheeler.

RS: I have to name two people—I love the humor of Tammi Sauer and the rhyming of Lisa Wheeler.

RVC: Complete the sentence in six words or fewer. Rob Sanders is a writer who…

RS: … teaches and a teacher who writes.

RVC: Thanks, Rob. It was great having you back here with us at OPB.