Our April Author Interview is with Elisa Boxer, a Maine-based writer and Emmy-winning journalist. You might’ve seen her writing at The New York Times, Fast Company, and as part of the Today Show parenting blogging team, or you might’ve seen her as a former ABC news anchor. In the past few years, though, she’s gone from having a lifelong passion for reading children’s books to combining that passion with her storytelling skills and commitment to uncovering and sharing vital truths to write her own children’s books. Helping her manage this new kidlit writing career is literary agent Steven Chudney (see the OPB interview with him right here!).

Our April Author Interview is with Elisa Boxer, a Maine-based writer and Emmy-winning journalist. You might’ve seen her writing at The New York Times, Fast Company, and as part of the Today Show parenting blogging team, or you might’ve seen her as a former ABC news anchor. In the past few years, though, she’s gone from having a lifelong passion for reading children’s books to combining that passion with her storytelling skills and commitment to uncovering and sharing vital truths to write her own children’s books. Helping her manage this new kidlit writing career is literary agent Steven Chudney (see the OPB interview with him right here!).

As Elisa shares on her website: “seeing my own words unfold onto the page (I write everything out longhand first) helps bring into focus how journalism, teaching, mothering, mindfulness, advocacy, and writing are inextricably and cosmically intertwined for me.” That sounds like the recipe for something really good.

Let’s get right to that interview and learn more about how all these things play into Elisa’s life and career!

RVC: With most author interviews, I try to sleuth out that kernel of a moment that sparked a kidlit writing career. With you, however, I feel like I might need to go after that journalist AHA moment first. So, let me ask it this way—as a kid, what was your relationship to reading and writing?

EB: My kidlit writing career actually preceded my journalism career. But it’s understandable that this would have flown under your sleuthing radar, as it was the early 70s and The Kitten & the Puppy and Other Things had a relatively small print run.

EB: My kidlit writing career actually preceded my journalism career. But it’s understandable that this would have flown under your sleuthing radar, as it was the early 70s and The Kitten & the Puppy and Other Things had a relatively small print run.

Although as you can see, it did win a Coldicot (sic).

RVC: Absolutely glorious. Thanks for sharing!

But since my exhaustive sleuthing didn’t turn that up, I’m now doubting all of my “facts,” yet I THINK you studied journalism at Columbia. What were a few of the best writing lessons you learned there that helped in your subsequent career as a journalist?

EB: The best lessons I learned there were about jumping straight to the source for information. I didn’t have much of a choice, since those were pre-internet days where you couldn’t just look stuff up. But I was taking subways to Harlem and the Bronx at all hours, and hunting down interviews and stories and sources first-hand. Before that, I had been a crime reporter in Lowell, Massachusetts, a community where there was no shortage of crime. I was doing stories on girl gangs and drug rings. So, during the course of my time at the Lowell Sun and Columbia, I really got comfortable with pounding the pavement and gathering information the old-fashioned way. That was the only way to do it back then. This is all to say that I’m old.

RVC: What did you find most rewarding about old-fashioned journalism work?

EB: Telling the stories of people whose voices might otherwise go unheard… Whether it was a kid organizing a bake sale for his sick teacher, a lawmaker apologizing on behalf of the state for abuse that happened decades earlier at a state-run institution, or a domestic abuse survivor starting a shelter, I’ve always been drawn to shining a light on the unsung heroes.

RVC: That’s such a lovely way to explain journalism that’s done well. What motivated you to take the leap into the big ocean of children’s books?

EB: I rediscovered my love for children’s books when my son was born, eighteen years ago. Soon after that, I left full-time journalism, transitioning to part-time magazine writing and teaching newspaper reporting at the University of Southern Maine. In between classes and assignments, I drafted children’s book manuscripts. During those years, I attended several SCBWI conferences, and always left feeling invigorated and inspired. I never knew if I’d ever be published, but I knew I loved creating stories for kids.

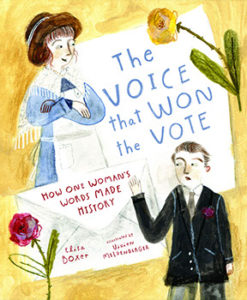

RVC: I’ve left more than a few SCBWI conferences feeling the same way. What was the story behind the story of your first picture book, The Voice that Won the Vote?

EB: It was 2017 and I had another social-justice related book out on submission. That one still hasn’t sold!

EB: It was 2017 and I had another social-justice related book out on submission. That one still hasn’t sold!

RVC: It happens to the best of us!

EB: Anyway, my agent, Steven Chudney, alerted me to the fact that the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment (which gave women the right to vote) was coming up in 2020. Being drawn to unsung heroes, I did an internet search for little-known women in the suffrage movement. When kids who are trying to come up with topics ask how I found this story, I always tell them to do internet searches for unsung heroes in whatever area they’re interested in. Because I literally typed into Google “little-known women in the suffrage movement.”

When I came across the story of Febb Burn, the mom who helped save suffrage, I felt that tug in my solar plexus to find out more. I went digging further, but couldn’t find any books about her, for adults or children. That really surprised me. She was such an inspirational figure and such a perfect representation of the idea that every voice matters. That’s when I knew I wanted to make her the subject of a picture book.

RVC: If you’re anything like the long-form journalists I know, you dive into research like a penguin goes for water. Given the page constraints of picture books, how did you grapple with shaping the story and choosing what went in and what didn’t?

EB: So true about the research and narrowing down what goes in. It’s such a challenge! With every book, I first make sure there’s an emotional resonance that’s relatable for kids–a universal theme that would make a great takeaway. In this case, the theme of every voice matters hooked me. I want every child to know how much their voice matters, so I looked for scenes from Febb’s life and from that time in history that either highlighted that theme, or challenged it. From there, I built a story arc, and if a scene didn’t contribute to that main idea, alas, I had to cut it.

RVC: I have to ask—what’s your favorite Febb fact that didn’t make it into the book?

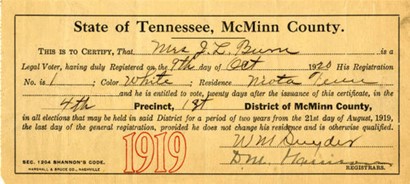

EB: After writing the letter that resulted in her son casting the tie-breaking vote for nationwide women’s suffrage, Febb became the first woman in Tennessee history to register to vote. Here’s her registration card!

RVC: WOW!

EB: Notice it says “his” registration. These cards were designed for men. I geek out over these historical documents.

RVC: What are some of the key differences between reporting a story and picture-booking a story?

EB: They seem so different, right? But there are many similarities–I’d say more similarities than differences. At least for nonfiction. Both involve choosing a topic, coming up with a hook, conducting research and interviews, writing outlines and drafts, ditching those and writing new ones, deciding which elements contribute to the story enough to make it in the final product, and then distilling those elements down to something relatable and (hopefully) interesting. So, whether it’s a newspaper article, a magazine story, a TV report, or a picture book, the information gathering and storytelling process is very similar.

I’d say the biggest difference is the timeline and turnaround time. Since daily journalism has much tighter deadlines, the process is sped up exponentially.

RVC: Aha. Makes sense! Care to give a specific example?

EB: In One Turtle’s Last Straw, for example, which comes out next month, I saw a viral video of marine biologists rescuing a sea turtle who’d gotten a straw stuck in his nasal passage and could barely breathe. I did some background research, and then interviewed the marine biologist who made the video. She happened to mention that this whole ordeal was likely the result of someone who had unwittingly tossed a straw in the garbage without giving it a second thought. I knew in that moment that’s how I wanted to begin the book, with a child casually tossing a straw in the trash. Same thing with journalism in terms of researching and reporting facts, details and quotes, and determining how to approach the story in a way that will resonate with readers/viewers.

EB: In One Turtle’s Last Straw, for example, which comes out next month, I saw a viral video of marine biologists rescuing a sea turtle who’d gotten a straw stuck in his nasal passage and could barely breathe. I did some background research, and then interviewed the marine biologist who made the video. She happened to mention that this whole ordeal was likely the result of someone who had unwittingly tossed a straw in the garbage without giving it a second thought. I knew in that moment that’s how I wanted to begin the book, with a child casually tossing a straw in the trash. Same thing with journalism in terms of researching and reporting facts, details and quotes, and determining how to approach the story in a way that will resonate with readers/viewers.

RVC: How does the editorial profess differ between journalism and picture books?

EB: Long-form journalism is fairly similar to picture books editorially, at least in the initial stages, in that you choose a topic, gather information, craft the story, and refine it. With books, you’re dependent on an editor/publisher to buy the text, whereas in journalism, you’re already hired! The whole part about no rejections is a plus. From there, with books as well as long-form journalism, there’s input and some back-and-forth with the editor. In daily journalism with the tighter deadlines and turnarounds, there’s less time for editorial input. Picture books remind me a lot of the days when I used to do packaged reports for television, in that the illustrator/videographer brings depth and feeling to the product in a way that the words alone never could. I have been so fortunate to work with incredibly talented photographers, videographers, and illustrators, and I am in constant awe of their ability to bring my words to life in a way that’s so much richer than I could have imagined.

RVC: At what point did you fully realize you were making a kidlit career and that you weren’t a one-and-done author?

EB: I’m still pinching myself, honestly. I think it was while we were waiting for The Voice that Won the Vote to come out, when I sold two books to Emily Easton at Crown/Random House, and then two books to Howard Reeves at Abrams, that I realized I could conceivably have this career that had been in my heart ever since The Kitten & the Puppy.

RVC: If you had to summarize the most important thing you’ve learned about writing nonfiction picture books, what would it be?

EB: Write the stories you care about, rather than the stories you think will sell. So much in this business is uncertain and counterintuitive. But if you stick with what calls to you, only good can come of that.

RVC: Let’s talk Nancy Pelosi. How did A Seat at the Table: The Nancy Pelosi Story come about?

EB: My agent gets the credit for this one, too! By the way, I’m loving that stick figure you drew for your interview with him.

RVC: Aw, shucks. I’ll have to start bragging to my illustrator colleagues at Ringling College about my near-criminally underappreciated mad art skills. Thanks for noticing! (To see that AWESOME art, check out Steven’s OPB interview right here). Back to you and the Pelosi book, Elisa!

EB: I had just finished writing The Voice that Won the Vote, and Steven and I were chatting about other barrier-breaking potential subjects. He suggested Nancy Pelosi. When I began researching her background and found out more about her childhood, I knew she’d make the perfect subject for a picture book.

EB: I had just finished writing The Voice that Won the Vote, and Steven and I were chatting about other barrier-breaking potential subjects. He suggested Nancy Pelosi. When I began researching her background and found out more about her childhood, I knew she’d make the perfect subject for a picture book.

RVC: What’s a common misconception about Nancy Pelosi?

EB: That she always had political aspirations. She actually grew up believing that women were supposed to stay out of the political spotlight, and that their role in politics was purely to help men get elected. She watched her mother do that. It wasn’t until a dear dying friend personally asked her to fill her Congressional seat that Nancy Pelosi actually considered running for office herself. And even then, she was hesitant.

RVC: In terms of your writing, what did you handle better in this book than in your first?

EB: That’s such an interesting question, because I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the element of this business where you pour your heart into a manuscript, sell it (hopefully), and then it’s another 2–3 years before it’s published as a book. And we’re ever evolving, right? I mean, I’m not the same person I was last week, let alone three years ago.

I feel like I am constantly aligning better with who I really am, and shedding old versions of me that maybe did things based on “shoulds” or expectations. And so with the books I have coming out this year, there are things I would have done differently had I started writing them now. I mean, I am super proud of them, but there’s phrasing I would have changed here and there, or a different approach I would have taken with this scene or that. So, to answer your question, I think each book represents the best of who we are at that point.

RVC: Along the way, you teamed up with a picture book PR group—the Soaring 20s.

EB: It’s such an amazing bunch of creators and remains one of the best kidlit decisions I have made! Writing can be such a solitary experience, and I was looking for a community of creators to not only help promote each other’s work, but to share insights about the business. What I hadn’t counted on was getting a close-knit group of great friends.

RVC: Could you talk a bit more about that group and what they’re/you’re all doing?

EB: It’s been extraordinary. Especially since we’ve been able to support each other through the ins and outs of publishing in a pandemic. For many of us, our debuts released just as the pandemic was beginning. My first book released March 15, 2020, which was the week that everything shut down. Several of us had our launch events and school visits cancelled, and together we were able to share insights on how to move forward virtually. When 2020 was over, we weren’t ready to say goodbye! Plus, many of us had new book deals. So, we decided to stick together for at least the next decade. 😀

RVC: From looking at your website and LinkedIn page, you sound terrifically busy. What do you do to de-stress?

EB: There’s a way to do that?

RVC: Who or what has most influenced your kidlit career?

EB: Definitely my son, Evan. He’s an everyday reminder to keep tapping into my heart, which is where all of my stories come from. Even the more academic stories. If I can’t write them with heart, I can’t write them.

RVC: One final question for this part of the interview because it’s brag time. What’s next for you in the world of kidlit? Are we going to see a fiction picture book?

EB: I do have a couple of fiction picture books in progress! One involves humor. I’m a bit stuck on it–I need to get funnier. I’m also writing a chapter book series and a middle grade novel. But on the more immediate horizon are several more nonfiction picture books: One Turtle’s Last Straw (Crown/Random House) coming next month, SPLASH! (Sleeping Bear Press) coming in July, Covered in Color (Abrams) in August, Hope in a Hollow (Abrams) in 2023 Tree of Life (Rocky Pond Books/Penguin) in 2024, and more in 2024 that haven’t been announced yet.

EB: I do have a couple of fiction picture books in progress! One involves humor. I’m a bit stuck on it–I need to get funnier. I’m also writing a chapter book series and a middle grade novel. But on the more immediate horizon are several more nonfiction picture books: One Turtle’s Last Straw (Crown/Random House) coming next month, SPLASH! (Sleeping Bear Press) coming in July, Covered in Color (Abrams) in August, Hope in a Hollow (Abrams) in 2023 Tree of Life (Rocky Pond Books/Penguin) in 2024, and more in 2024 that haven’t been announced yet.

RVC: Congrats on all of that. You’re going to be busy!

EB: Absolutely!

RVC: Now, Elisa, since you’re a journalist who knows about the mission-critical importance of tight copy and fast deadlines, you’re surely as prepared as anyone to kick butt on our SPEED ROUND! Let’s prove it now. Zoomy quick questions and whizzy fast answers please. Are you prepared?

EB: No! I tend to be slow and methodical. Unless I am on deadline, then I can be zoomy and whizzy. Although actually I AM on deadline because I left these until the last minute.

So, yes, I’m ready! Fire away!

RVC: Tea, coffee, or soda?

EB: Pineapple and banana smoothie.

RVC: What inanimate object would be most annoying if it pumped out loud, upbeat music every time you used it?

EB: My son just said a toothbrush, because you hold it close to your head. He has a point, no? That would be really annoying.

RVC: What word do you always mispell misspel write wrong?

EB: Suppress (I always want to add an “r” before the first “p”) and precede (I always want to double the middle “e”).

RVC: What books are on your nightstand?

RVC: What books are on your nightstand?

EB: Martha Beck’s Finding Your Own North Star and a notebook for writing down dreams and story ideas in the middle of the night.

RVC: What’s a great nonfiction picture book that too few people know about?

EB: Wait, Rest, Pause: Dormancy in Nature, by Marcie Flinchum Atkins. I love this book for many reasons, including the fact that it helped me to be okay with slowing down. The book came out in 2019. I had just been diagnosed with chronic Lyme disease, after spending a couple of years with a mysterious debilitating illness. Glorious photographs and Marcie’s comforting text reveal plants and animals that stop, slow down and take deep, meaningful pauses before emerging in a new season. At the time, I was frustrated with my inability to be active. I’ve always looked to the natural world for inspiration, and this book was a profound reminder that maybe this was a period of time when my body needed to rest and build strength from within.

EB: Wait, Rest, Pause: Dormancy in Nature, by Marcie Flinchum Atkins. I love this book for many reasons, including the fact that it helped me to be okay with slowing down. The book came out in 2019. I had just been diagnosed with chronic Lyme disease, after spending a couple of years with a mysterious debilitating illness. Glorious photographs and Marcie’s comforting text reveal plants and animals that stop, slow down and take deep, meaningful pauses before emerging in a new season. At the time, I was frustrated with my inability to be active. I’ve always looked to the natural world for inspiration, and this book was a profound reminder that maybe this was a period of time when my body needed to rest and build strength from within.

RVC: What are five words that describe your picture book writing philosophy?

EB: Search for the story’s soul.

RVC: Thanks so much, Elisa! Best of luck with all those new books.

EB: Thank you so much, Ryan! It was really great connecting with you!

This month’s Author Interview is with Toni Buzzeo, a New York Times bestselling picture book author. Welcome, Toni!

This month’s Author Interview is with Toni Buzzeo, a New York Times bestselling picture book author. Welcome, Toni!

We’re starting off 2022 with an author/illustrator interview with

We’re starting off 2022 with an author/illustrator interview with

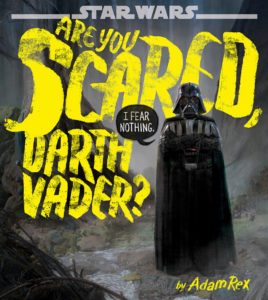

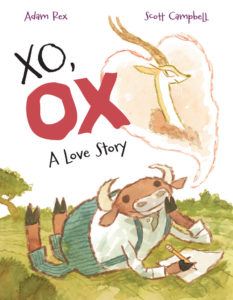

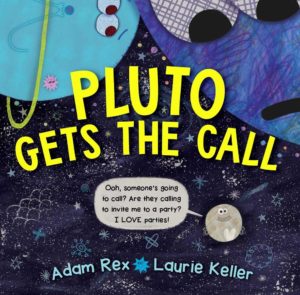

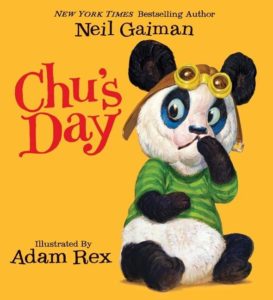

We always like to end the year strong, and thanks to December’s guest author interview, we’re doing exactly that. Welcome to Only Picture Books, Adam Rex!

We always like to end the year strong, and thanks to December’s guest author interview, we’re doing exactly that. Welcome to Only Picture Books, Adam Rex!