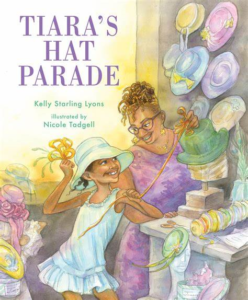

Tiara’s Hat Parade

Author: Kelly Starling Lyons

Illustrator: Nicole Tadgell

Albert Whitman & Co.

1 April 2020

32 pages

This month’s PB review is by Ryan G. Van Cleave (champion hat-wearer at Only Picture Books) and Ringling College of Art and Design Illustration Professor (and OPB friend) David C. Gardner.

–Ryan’s Review of the Writing–

This new book by Kelly Starling Lyons tells a tale you don’t often see in picture books–capitalism. Tiara’s momma is terrific at making hats, but along comes a new store in town that sells them cheaper, so when Momma’s sales bottom out, she reluctantly shuts down her small business–the Tracy Rose Millinery. But Tiara isn’t fine with that because she loved Momma’s creations, and not just because Tiara was its top hat model.

Even though Momma eventually finds another outlet for her creativity–teaching art at Tiara’s school–it’s not the same. She’s clearly still sad about her defunct business and no longer being able to make her beloved hats for friends, family, and the community. Tiara can tell how much Momma misses it. So, when it’s time on Fun Friday to choose the next class art project, Tiara suggests, “Hats!” That’s what the class does, and Momma and the students have a blast.

But Tiara takes it a step further. She advertises a Hat Parade at Height Elementary, with the request that people come and wear their favorite Tracy Rose hat. They come out in droves with each taking a turn on stage to model their hats and share how empowering and individually meaningful they are. Momma is touched, and she starts to get orders for new hats once again. Maybe, too, Tiara has discovered her own future calling as well after finding great pleasure in helping her friend, Matti, improve on her art class creation.

I’ll leave it to David to speak about how these interesting visuals complement the story, but Tiara’s Hat Parade goes well beyond the tale of a small business that fails and finally comes around again thanks to community spirit. It’s also about a young girl’s indefatigable spirit and deep love for family. A thoughtful Author’s Note also shares the author’s own experience with hats and explains how they are a vital part of Black women’s–and men’s–style. A list of Famous Black Milliners is an added bonus to the back matter.

This emotional-but-triumphant story utilizes language at times that matches the beauty of Momma’s fine hats, which is a very nice touch.

4.25 out of 5 pencils

– David’s Review of the Illustrations–

The illustrations by Nicole Tadgell are light, lively, and expressive. They highlight the characters’ relationships, never missing an opportunity to show characters interacting playfully with one another. The text relies on these relationships to tell the story, but the pictures show us these relationships–the closeness, the joy and the humor–in a way the text cannot, from Tiara’s closeness to her mom, to the joy in the big finale, the hat parade, the women’s outfits, colorful and varied.

The expressions of the characters are clear on every single page due to Ms. Tadgell’s thoughtful depiction of facial expressions, body language, and her attention to the emotions of color. For example, when Tiara’s mother and her family go through hard times, the colors take us down, cool and desaturated, without dipping too far down into mere drabness.

Even in a sad moment though, there is a fluidity and charm to Ms. Tadgell’s style, due in part to the sensitivity of the watercolor paintings and the light, loose holding line of the pencil which, at its best, recalls the charm of Trina Schart Hyman’s classic work. The mother, in particular, rings true. Using specific details, such as her distinctive hairstyle, glasses, and even the type of clothing Momma chooses to wear, she leaps from the realm of generic mother to being a warm, real person. There’s the visual contrast between Tiara, thin and angular, and Momma, round and soft, which sets up a pleasing–and essential–variety to the central relationship of the book.

The great success of these pictures is the emotion they convey on every page, and, by extension, the connections and relationships: Mother and daughter dancing in the hat shop to friends’ applause (a clever visual foreshadowing of the climactic parade), the family gathered around the dinner table in unspoken sadness, Momma dancing in front of her giddy students at school. The colorful hat parade of the title splashes across a series of pages, each wonderfully realized model/friend alive in a spotlight of her own. A sense of community, togetherness, and fun is conveyed through the characters’ constantly moving–dancing, strutting, reaching–and through the colors, bright but never garish.

Ms. Tadgell skimps a bit on the background details now and then, such as a window frame that feels sketched in as an afterthought and could have used the same loving attention as the observed detail on Momma’s dress or a nearby jade plant. Proportions and perspective in the drawings feels a bit off at times. But those details seem minor considering the overall fun in the spot-on hat designs and colors, full of rich, observed detail.

It’s clear to see why Tracy Rose’s hats bring so much joy to others, and clearly these pictures will delight any child.

4.5 out of 5 crayons

David C. Gardner is an award-winning illustrator and visual development artist. A former artist for Walt Disney Animation Studios, he has illustrated numerous picture books, including his latest from Sleeping Bear Press, Write On, Irving Berlin! by Leslie Kimmelman (which appeared on OPB in May 2018). It tells the true story of little Izzy Baline, who immigrated to New York City in 1893 and grew up to become Irving Berlin, one of the most well-known composers of popular music in America. David teaches illustration at Ringling College of Art and Design.

David C. Gardner is an award-winning illustrator and visual development artist. A former artist for Walt Disney Animation Studios, he has illustrated numerous picture books, including his latest from Sleeping Bear Press, Write On, Irving Berlin! by Leslie Kimmelman (which appeared on OPB in May 2018). It tells the true story of little Izzy Baline, who immigrated to New York City in 1893 and grew up to become Irving Berlin, one of the most well-known composers of popular music in America. David teaches illustration at Ringling College of Art and Design.