Welcome to Roxanne Troup, the subject of our September Author Interview.

Welcome to Roxanne Troup, the subject of our September Author Interview.

These days, Roxanne lives in Colorado where she writes children’s books, hikes in the mountains, and cheers on her kids at sporting events. She also “visits schools to water seeds of literacy and teach about writing. (And sometimes remembers to water the plants in her own garden.)”

In addition to being the author of more than a dozen children’s books, she’s also a ghostwriter, a work-for-hire writer, a speaker, and a history fan (“I find history fascinating because it’s full of stories. But I only realized that as an adult. As a kid, I only remembered the history I lived.”)

Need a few fun facts, too? Try these:

- She’s afraid of octopuses.

- She grew up in a historic home along the waterways of Missouri.

- She’s a certified chocolate lover (“If they gave out licenses for this, I’d definitely have one!”)

Let’s move straight to the interview to find out more about our new writer pal!

RVC: You’ve got a very unusual story about how you discovered your love of reading. Care to share?

RT: I was an early reader. And while I don’t remember ever not reading, I vividly remember the summer I fell in love with reading. I was seven, and my little brother wasn’t too happy about it. He wanted to play imaginary games with me, not watch me read “boring books.” But I’d recently broken my neck in a tumbling accident, and after spending nearly six months in a neck brace followed by more months of physical therapy (and intermittent neck-brace-wearing), I’d gotten used to “boring.” For over a year, I couldn’t ride my bike or play on our swing set without wearing the brace. But I could read. And I read everything I could get my hands on.

RVC: Wow!

RT: During the school year, I was in the library every day. I sped through easy readers by Syd Hoff and Peggy Parrish. I checked out everything my library had by Judy Blume and Beverly Cleary. And that summer, I read whatever I could find in our house—from Disney’s Encyclopedia of Knowledge to old books like Life with Father. (And by “old,” I mean old. My dad was a teacher who couldn’t stand the thought of throwing books away, so every time his school updated their curriculum or the library updated their collection, we did too. Our attic was full of books!) Then, I stumbled upon Pippi Longstocking and The Borrowers and time disappeared. Reality melted away. I was no longer reading because I didn’t have anything else to do. I was hooked. I read those books over and over and over again.

RT: During the school year, I was in the library every day. I sped through easy readers by Syd Hoff and Peggy Parrish. I checked out everything my library had by Judy Blume and Beverly Cleary. And that summer, I read whatever I could find in our house—from Disney’s Encyclopedia of Knowledge to old books like Life with Father. (And by “old,” I mean old. My dad was a teacher who couldn’t stand the thought of throwing books away, so every time his school updated their curriculum or the library updated their collection, we did too. Our attic was full of books!) Then, I stumbled upon Pippi Longstocking and The Borrowers and time disappeared. Reality melted away. I was no longer reading because I didn’t have anything else to do. I was hooked. I read those books over and over and over again.

RVC: I know exactly what you mean about reality melting way when you find the right books. It seems like you had every intention of being a lifelong educator. What appealed about the classroom?

RT: All the things I love about writing for kids: The curiosity; the creativity and resourcefulness; the humor. Kids are intuitively confident and smart. They’re artists, athletes, mathematicians, scientists, and engineers—all the things they forget they are and wish they could be as preteens. If I could help nurture that innate wonder and willingness to fail, even for a short time, I wanted to.

RVC: When did you first consider yourself to be a writer?

RT: Not until 2016. Even though I was consistently making money writing (I got my first writing-related paycheck in 2009), it wasn’t until I decided to focus on kidlit that I started calling myself a “writer.” Instead, I’d say things like “I’m doing some freelance work” or “I’m ghostwriting.” Writing was something I did to help put food on the table and gas in the car. It wasn’t who I was. It took really immersing myself in the kidlit industry (and publishing my first kid’s book) to change that perspective.

RVC: Normally, I spend more time outlining an interview subject’s career and writing arc, but I want to jump ahead here. Why? Because I’m fascinated by how you’re keeping up successful careers as a picture book author, ghostwriter, freelance writer, freelance editor, and speaker. And all without an agent. Clearly, you have a good sense of the business side of things. So, how do you balance the creative side of writing with the business side?

RT: Some days not very well. But I had an epiphany a few years ago that if I wanted to do the thing I loved (write picture books), I had to start balancing and pruning my writing activities until all the writing I did connected to children’s books/education in some way. I have an in-depth presentation on this topic that I’ve given at my local SCBWI, but essentially, I discovered my writing niche—the thing that allows me to meet my goals (get paid via writing, get published under my own name, and write something I enjoy) without draining my creative reserves or taking time away from my family. Before that, I lived at the mercy of my inbox.

RVC: Please tell me more.

RT: Not to bore anyone, but as an example: I never advertised my ghostwriting services. Still, word has a way of getting around, and after a year or two ghosting, I found myself with so many clients I couldn’t do anything else. My family began feeling the pressure and I became frustrated. My clients were needy. They came to me unprepared, and, while the whole family enjoyed my paychecks, I didn’t enjoy what I was doing. So, I raised my fees to weed out clients and maintain my earnings, which gave me more time to do what I loved. I repeated that process several times before eventually deciding I wouldn’t take on any more adult ghosting clients. (I do still ghost for a few clients/publishers I have a track record with.) Instead, I would focus on kidlit. Now I consult with one of the most prestigious ghosting firms in the nation—working almost exclusively on picture books. I have more time. I still get paid to write, and it’s good practice doing what I love. I’ve done that in each of my freelance service areas, and while there are still days that feel more “business‑y” and less “kidlit‑y” and creative than I like, publishing is a business that requires both. So, I just remind myself of that and work toward a better-for-me balance the next day. And on the days I don’t have anything pressing, I work on my own projects. It’s still not a perfect balance, but it is getting better.

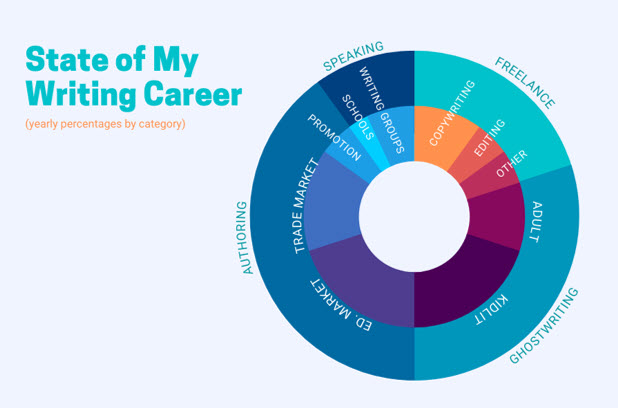

RVC: If you had to make a pie chart or Venn diagram to show your writing career right now, what would it look like?

RT: Nothing in real life is this neat and tidy, but in general, I spend the bulk of my writing time on…

RVC: How many different projects are you typically working on at any one moment?

RT: It varies from week to week (and I tend to think/schedule in monthly chunks), so I’m not exactly sure how to answer this except to say—several.

Some of my work is seasonal, like writing websites for schools. Other stuff is tied to publishing cycles—like my upcoming picture book release—so even though it’s on my calendar, the work I need to do for it is sporadic. I nearly always have two or three different freelance projects in various stages of development on my monthly calendar, as well as trade market research and submissions to track (and, on occasion, contract negotiations!). Depending on the season, I may also have education market projects happening—but when I do, I try to limit the amount of time I dedicate to freelance gigs. I’m still building my income stream for speaking, so that piece of the pie is also sporadic. Everything considered, it’s unusual if I don’t have a least one writing-related deadline each week.

RVC: Let’s talk books. This year, you’ve got not 1, not 2, not 3, not 4, not 5, but 6!!! kidlit books coming out this fall. These aren’t traditional trade books, but rather work-for-hire. Please explain the difference.

RT: Trade books are the books you’re familiar with; you find them in bookstores and associate each one to a specific author. Typically, that author has created the book from scratch and “sold” it to a publisher. (Publishers don’t actually buy books/manuscripts. They purchase “rights” to a work—like the exclusive right to publish and sell a work in English, or the right to create an audiobook of the work, etc. Each of these rights is negotiated in a contract between the creator and the publisher, but unless sold, the copyright always remains with the creator.) Often, creators receive an advance against royalties for these books, and since they receive a royalty off every book sold, they’re heavily invested in marketing and promotion.

Work-for-hire books are different—from the copyright level up. Work-for-hire is a copyright term that means, “work made on behalf of another, in which the commissioner owns the copyright.” (That’s my layman’s definition.) It’s sometimes referred to as “work made for hire” or WFH. Work-for-hire can be anything from ghostwriting to the creative work you do as an employee. But in all WFH, the individual or company that hires you to create the work owns the copyright to whatever you created. Once the work is completed and you are paid, the individual or company can do what they like with that work—edit it, publish it, sell it, whatever—it belongs to them. Sometimes the creator gets credit for works made for hire. Sometimes they don’t. In general, WFH writers are paid a flat-fee for their work, and thus are not expected to promote it.

RVC: Thanks for the explanation here. How does WFH work in kidlit?

RT: In kidlit, work-for-hire typically involves two markets: the education market and IP, or intellectual property. The education market is work created for (and sold to) schools and libraries. Publishers generate the ideas for these books/series based on school curriculum and market need. They’re not typically available in bookstores, but authors do get credit for them. And since educational publishers have established relationships/reputations with the schools and libraries that purchase these books, authors can expect that lots and lots of kids will read their work.

The IP market includes anything an author didn’t think up themselves. It can be a series cooked up by a publisher/packager to meet a market demand, ghostwriting, or a book featuring licensed characters like Spider-Man. IP books are generally sold in bookstores alongside other trade books. And, for the author, can range from flat-fee to royalty-based contracts (though you should expect any royalty to be lower than what you’d receive from a work you thought up and created yourself). These books sell really well! Some of your favorite series might even be on the list.

If you’re interested in learning more about work-for-hire writing, specifically in the education market, I have an article on LinkedIn you might enjoy.

RVC: What are some of the unexpected benefits of writing work-for-hire kidlit?

RT: WFH is a great source of additional income. Unlike trade projects, WFH is a guaranteed sale/paycheck. It keeps me writing (which we all know is a necessary part of improving craft) and gives me experience working with and thinking like editors. It builds my portfolio and can give me books for use in soliciting author visits. And because WFH is generally flat-fee, I’m not expected to participate in marketing—which, especially this year with six books coming out in one season, is a relief. (Can you imagine having to promote six books at once!?!?)

RVC: I sure hope so since I’ve got six coming out next year. Let’s talk about that later! Now, how are you getting these deals without an agent?

RT: With the exception of IP projects, most agents don’t handle WFH deals. The flat-fee model just isn’t worth it for them. So, I contact publishers/packagers directly with a submissions packet. A WFH submissions packet includes a cover letter expressing your interest and areas of expertise, a resume/CV, and targeted writing samples. The publisher keeps your info on file and contacts you with projects that fit your experience and/or samples.

RVC: What about the ghostwriting gigs?

RT: The ghostwriting I do for adults has all happened organically. The kidlit ghostwriting I do comes both organically and through the firm I consult with. I’d love to get more licensed character IP work—especially in the early reader and chapter book markets—but from what I understand, those jobs typically route through an agent or established editorial relationships.

RVC: Are you actively seeking an agent?

RT: Yes and no. I don’t currently have anything out with agents, but if I see that someone is reopening to subs or has a specific wish list item that fits what I create, I don’t hesitate to query. I’m just not spending a ton of time researching agents or sending them work. I’m not opposed to working with an agent—I’d love to be able to walk through the doors an agent can open for me—I’m just not waiting around for one either. I know, whether I have an agent or not, my career is in my hands.

RVC: What’s the most common misconception about work-for-hire work?

RT: That it’s a fast and easy “back door” into publishing. While WFH timelines are shorter (books typically release a year or less after contract), the work itself does not require any less effort. Good writing is good writing regardless of genre or sales avenue. And readers are readers. They deserve for authors to be just as meticulous with research, just as purposeful with word choice and mechanics, just as enthusiastic and creative (if appropriate) with WFH as any other contract.

RVC: You’re doing a lot of adult work, too, with your writing. In what ways does that affect your kidlit efforts?

RT: I do try to limit the amount of adult work I’m taking on so I don’t completely derail my kidlit efforts. But even adult projects are beneficial. The paychecks I get for adult freelance work helps subsidize the work I really want to do. It also improves my writing craft and marketing skills. To succeed in this industry, I have to be able to transfer thought to page in a coherent manner. I also have to be able to “sell” myself and/or my work to agents, editors, booksellers, parents, teachers who might want to invite me into the classroom, and all sorts of other “gate keepers” (which is really just an ominous-sounding phrase for book buyers.) And all those things take practice. Adult freelance forces me to practice.

RVC: This is a picture book blog, so I have to ask this—what’s the story of your first published picture book, My Grandpa, My Tree, and Me (Yeehoo Press, March 2023)?

RT: Somewhere on social media, I saw a post about a new publisher. I went to their website and saw they were looking for agricultural books so I started researching. When I ran across a YouTube video of a farmer harvesting pecans, I knew I had my topic. I couldn’t get the image of the farmer shaking that tree out of my head—all those pecans falling like torrential rain.

Growing up in a farming community, I had some experience with agriculture and pecans. But no one I knew harvested pecans by tractor. We gathered pecans like the wild products they were, not from hundreds of trees at a time. This dichotomy provided the structure of the story, and my first draft came together quickly.

Unfortunately, I was the most experienced writer in my critique group and started submitting before I should have. I sent the manuscript to four different publishers with no response. On the fifth try an editor saw enough potential in the work to request an R&R (revise and resubmit). I didn’t agree with the direction they wanted me to take the story, but tried to figure out what underlying issue they were pointing out. Eventually I realized my draft was too “education market‑y.” I had to figure out how to make it work for the trade market. I went back to work and a month or so later had an opportunity to submit my new draft to the wonderful Katie Heit at Scholastic. The story was too quiet for Scholastic’s list, but she was so complimentary I knew I’d hit the right note with my revisions. I spent the next year-and-a-half submitting, but now, I was getting responses.

I finally found my publisher in May of ’21—Yeehoo Press. Yeehoo pubs picture books that work for both the US and Chinese markets, so my informational fiction was perfect for them. Four months later, it was official. My first trade PB was under contract!

Yeehoo contracted Kendra Binney to illustrate. Her soft watercolors were the perfect pairing for my lyrical text. I’m excited for its upcoming cover reveal!

RVC: What was the most valuable lesson that book taught you?

RT: To be patient—and keep working. Good writers get turned down all the time. Published writers get turned down, too. But as cliché as it sounds, it really does take just one “yes.” Publishing is a partnership. You have to be patient to find the perfect partner for your particular story, and you have to keep working to make sure your story is the perfect fit for a particular publisher.

RVC: Please talk about the role of community in your writing life.

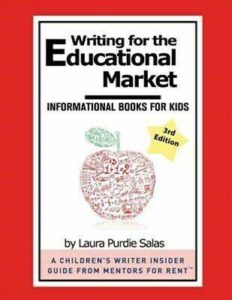

RT: When I first started writing kidlit, I couldn’t justify the cost of writing classes or even an SCBWI membership. But I joined Laura Purdie Salas’ Facebook group for writers (now defunct) and started lurking and learning. Laura taught me a ton—just by following her career and reading her comments on people’s posts. She was so helpful and kind, but also honest. When she created Writing for the Educational Market, I knew it would be practical and encouraging, just like her. I purchased it immediately and got my first book contract shortly thereafter. I highly recommend her workshop-in-a-book to everyone interested in the education market. It’s full of info I couldn’t find anywhere else. (And believe me; I looked!)

RT: When I first started writing kidlit, I couldn’t justify the cost of writing classes or even an SCBWI membership. But I joined Laura Purdie Salas’ Facebook group for writers (now defunct) and started lurking and learning. Laura taught me a ton—just by following her career and reading her comments on people’s posts. She was so helpful and kind, but also honest. When she created Writing for the Educational Market, I knew it would be practical and encouraging, just like her. I purchased it immediately and got my first book contract shortly thereafter. I highly recommend her workshop-in-a-book to everyone interested in the education market. It’s full of info I couldn’t find anywhere else. (And believe me; I looked!)

RVC: Thanks to your rec, I just ordered a copy myself. Watch out, educational market!

RT: After a few WFH books, I wanted to jump the fence, so to speak, into the trade market. Laura’s career convinced me it was possible, but I needed to find a regular critique group—not just occasional online swapping partners. So, I joined SCBWI and started getting involved in my local group. It was so refreshing to find people who got what I was trying to do. They understood the struggles of writing kidlit, but also the joy of finally finishing a decent draft.

Today, I co-lead that group. And over the years, I’ve come to realize how incredibly generous and supportive the entire kidlit community is—if you are willing to put in the work.

RVC: What’s your most important good writing habit or routine?

RT: To write—whether I feel like it or not. I can’t wait for the muse to strike. I have deadlines. I have to get something on the page. If it’s no good, I can edit it. But I can’t edit a blank page. Eventually, if I put in the work, I’ll have something I’m proud of.

RVC: Lastly, what advice do you give to aspiring picture book writers?

RT: Learn the business and take the time to develop your craft. While writing may be creative, publishing is a business. You have to get both right to be successful. How? Read. A lot. Write even more. And find a group of creatives who can help you get better (not just those who will gush over whatever you create).

RVC: One final question for this part of the interview. Beyond the six work-for-hire books coming out this fall, what’s something upcoming that you’re really excited about?

RT: My debut trade picture book releases in March. That’s really exciting! (As a newbie, I’m still not sure what all that will entail, but I’m doing my best to learn as I go.) And I just signed a contract for another trade picture book slated for Spring 2024.

RVC: Congrats on that, Roxanne. But now the first part of the interview is over. Now it’s time for…the…LIGHTNING…ROUND!!! Are you ready?

RT: Ready.

RVC: What secret talent do you have that few would expect?

RT: I randomly remember lines to songs and movies from my childhood and use them in everyday life. When my children are being overly emotional—“Calm yourself, Iago” (in the voice of Jafar from Disney’s Aladdin). When my mother-in-law finally goes home—“I think we’re alone now” (from Tommy James and the Shondells). When someone asks me a stupid question—“It’s possible, pig” (as Westley from The Princess Bride)—though not always out loud!

RVC: Pick a theme song that describes where your life is at right now.

RT: “The Hustle” by Van McCoy.

RVC: What picture book author would you want to write YOUR life story?

RT: She doesn’t write nonfiction, but Beth Ferry. I love everything she creates.

RVC: Five things you can’t do your work without.

RT: A computer and Internet connection, Microsoft Office, a big desk calendar, and the library.

RVC: Who sets the standard for picture books about history?

RT: Oh gosh. There are so many really good ones … Barb Rosenstock.

RVC: What’s the best compliment a child ever gave you or your books?

RT: Now, I get it!

RVC: Thanks so much, Roxanne! And for those of you who read to the very end, OPB has a treat for you. Watch for an OPB cover reveal this week for Roxanne’s forthcoming picture book, My Grandpa, My Tree, and Me!

This month’s Author Interview is with Linda Elovitz Marshall, who’s a “writer of books for young children and other cool stuff.” I know her from a previous critique group and from Jane Yolen’s Picture Book Boot Camp. With all the success Linda’s having lately, it seems the right time to find out why.

This month’s Author Interview is with Linda Elovitz Marshall, who’s a “writer of books for young children and other cool stuff.” I know her from a previous critique group and from Jane Yolen’s Picture Book Boot Camp. With all the success Linda’s having lately, it seems the right time to find out why.

This month’s Author Interview is with Jocelyn Watkinson. The idea for her debut picture book–

This month’s Author Interview is with Jocelyn Watkinson. The idea for her debut picture book–

This month’s picture book author is yet another journalist—we’ve got quite a surprising streak going here! Welcome to Kaitlyn Wells, an award-winning journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and The Washington Post, among others. Since she’s an expert on diverse literature, you can readily find her writing about that at The New York Times Book Review, BookPage, and Diverse Kids Books.

This month’s picture book author is yet another journalist—we’ve got quite a surprising streak going here! Welcome to Kaitlyn Wells, an award-winning journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and The Washington Post, among others. Since she’s an expert on diverse literature, you can readily find her writing about that at The New York Times Book Review, BookPage, and Diverse Kids Books.

Our April Author Interview is with Elisa Boxer, a Maine-based writer and Emmy-winning journalist. You might’ve seen her writing at The New York Times, Fast Company, and as part of the Today Show parenting blogging team, or you might’ve seen her as a former

Our April Author Interview is with Elisa Boxer, a Maine-based writer and Emmy-winning journalist. You might’ve seen her writing at The New York Times, Fast Company, and as part of the Today Show parenting blogging team, or you might’ve seen her as a former