This month’s Industry Insider Interview is with Lee & Low Books’ Editorial Director, Cheryl Klein. She’s been on my Wish List for OPB for some time, so when I was asked in the 11th hour to provide a super-brief intro for Cheryl’s talk at the SCBWI regional conference in Miami this past January, I knew the literary gods were smiling upon me.

This month’s Industry Insider Interview is with Lee & Low Books’ Editorial Director, Cheryl Klein. She’s been on my Wish List for OPB for some time, so when I was asked in the 11th hour to provide a super-brief intro for Cheryl’s talk at the SCBWI regional conference in Miami this past January, I knew the literary gods were smiling upon me.

To a roomful of SCBWI members, I shared these three things about Cheryl by way of an introduction:

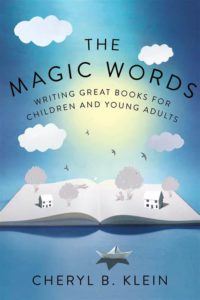

1–“As a writing professor and creative writing program director, I regularly loan out writing craft books to students. That includes Cheryl’s The Magic Words: Writing Great books for Children and Young Adults.” [Then I turned to Cheryl and fake glared at her.] “Yours almost never comes back. I’ve had to buy many, many copies of it over the years. So THANKS for that!”

2–“My literary agent and I were recently talking about picture book editors recently. When Cheryl’s name came up, my agent simply said: ‘She’s good people.’ That’s all I needed to hear.”

3–“Since I launched OPB back in April of 2018, I’ve always had a short Wish List of people I wanted to interview. Some I landed. Jane Yolen. Liz Garton Scanlon. Floyd Cooper. Rob Sanders. Elizabeth Harding. Sylvie Frank. But a few have so far eluded me. One name that’s moved to the top of my 2019 OPB Wish List? Cheryl Klein.” [I now pretended to whisper to the crowd as if Cheryl wasn’t standing six feet to my right.] “I’m hoping that this fancy-pants introduction might just tip the odds in my favor.”

And here we are, OPB and Cheryl–all thanks to social pressure, some literary luck, and good old-fashioned schmoozing (and I mean that in only the best sense of the word “schmoozing,” which is really just networking, acting like a pro, and being pleasant, vs. people who are crazy, stalkery, and IN-YOUR-FACE pushy–we’ll do a special OPB Bonus Goodie on that “Don’t Do This!” topic another time).

But now that we’re all here and ready to go, let’s get cooking! Take it away, Cheryl!

Website: www.cherylklein.com

Facebook: www.facebook.com/cherylkleinedit/

Twitter: www.twitter.com/chavelaque

MS Wishlist: www.mswishlist.com/editor/chavelaque

RVC: Unlike most editors, you almost had another career … as a spy. How did that (almost) happen?

CK: As a former Midwesterner, I pride myself on my ability to be nice, bland, and unobtrusive to the point of inconspicuousness when I so choose. This served me well in making me a good observer and allowing me to pass through most places unremarked-upon—even if I was, say, carrying the unpublished manuscript for the seventh Harry Potter book (which I did once).

The privileges of being a middle-class-ish white lady help here too, of course.

RVC: As a fellow former Midwesterner, I, too, have been known to enter a crowded room and not be noticed until I had my foot stepped on. Depending on how you look at that, it might be considered a gift.

But back to your non-spy career. Once you started working at Lee & Low, how did you know that you’d found your true calling? What were the signs?

CK: I’ve worked in the industry for nearly nineteen years now, and I felt like it’s my calling since day one. The main sign of that calling is the quality of my books and my relationships with my authors, I think, and how content I feel when I’m doing the work … the “mechanic’s delight,” as the late Canadian writer/editor Brian Doyle called it, of seeing how much stronger a scene in a novel might be when we take out all the filter words, or discovering a new illustrator’s portfolio and connecting her with a manuscript that lets her talents shine. It makes me deeply happy to make books right or better. And one of the best parts of being an editorial director is helping my team figure out their own rights or betters, and do their best work too.

RVC: I sometimes hear writers bemoan how the days of Maxwell Perkins and hands-on editors is long gone, and that most editors are just gatekeepers. Could you help dispel that myth by explaining some of the actual work that goes into taking a single picture book manuscript from promising-manuscript-I-acquired to the-best-thing-we-collectively-can-create?

CK: This varies from manuscript to manuscript, and with whether the author is illustrating the book as well, but the process usually runs in three stages. In the first, the author and I think and talk about the concept or point of the book—what the story is, what the author wants to convey, how the project as a whole should feel to readers, where the child’s and adult’s pleasure or interest in it might come from. Here I write (typically long) letters saying what I’m presently seeing in the text, and asking how that differs from the author’s vision, and then defining and explaining what I hope to see in the book long-term, if the author agrees. We talk that over until the author is ready to go off and revise.

In the second stage, the author takes all that feedback and conversation and moves around the necessary story pieces—or invents new ones—to put the book in a form that conveys the story and those thoughts and feelings compellingly. That might involve setting up a theme or idea on p. 4 that will then pay off on p. 26, or switching out one plot event for another, or just building out a character’s emotional arc a little more. With some manuscripts, we also try to figure out pagination at this point, while with other projects, I might leave that to the illustrator.

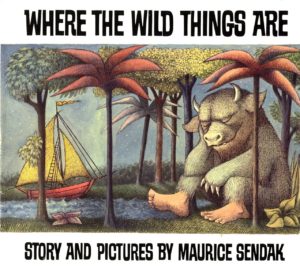

And in the third stage, we try to refine the language so it sounds marvelous when read aloud, leaves plenty of space for the illustrator, etc., etc. Here I do a lot of line-editing on paper or in Track Changes, going back and forth until everything feels and sounds right to me and the author. Stages II & III tend to bleed into each other a lot, actually, because so much of the sense of picture books is in the sound of them—how a thought or emotion is phrased, even things like word choice. I always think about the fact that Where the Wild Things Are would be infinitely last satisfying if the last phrase were “and it was still warm.”

And in the third stage, we try to refine the language so it sounds marvelous when read aloud, leaves plenty of space for the illustrator, etc., etc. Here I do a lot of line-editing on paper or in Track Changes, going back and forth until everything feels and sounds right to me and the author. Stages II & III tend to bleed into each other a lot, actually, because so much of the sense of picture books is in the sound of them—how a thought or emotion is phrased, even things like word choice. I always think about the fact that Where the Wild Things Are would be infinitely last satisfying if the last phrase were “and it was still warm.”

RVC: Unlike most picture book editors, you’re also an author. In fact, you have two picture books coming out in 2019. What advantages might you have by being both an editor and author versus solely being an author?

CK: Mostly it’s that I have an intimate knowledge of what’s going on behind the scenes, from what might be happening in an Acquisitions meeting, through the thought process my editor might be going through in phrasing a revision request a specific way. This could be crazy-making in the sense that I could worry, “Oh man, I heard that Barnes & Noble wants picture books with longer texts. Will the B&N rep speak up against my twelve-word text in the Acquisitions meeting?”

RVC: I think all writers hear rumors/trends like that from time to time and panic. A bit. Sometimes a lot.

CK: And while those thoughts do pass through my head, I’ve also been around the industry long enough to know that (a) a lot of this stuff is entirely out of my control, and hence not worth spending mental time on, if I can avoid it; (b) it isn’t personal – someone not liking my writing (particularly for market reasons) has nothing to do with who I am as a person, and my work has integrity no matter what that someone thinks; and © publishing opinions are never definitive or final. In six months, B&N may be begging for short texts, or an editor who didn’t respond to a text once might come around in a year or so and say “Hey, you know what? I can’t stop thinking about that manuscript, and now’s the right time to publish it.” (I know this in part because I have been that editor!) I’m also aware of just how much behind-the-scenes work is going on for a book, even when the author can’t see it, and I’m deeply grateful for that. So my knowledge of how things work mostly helps me let go.

RVC: Do you handle getting editorial notes any better than the rest of us?

CK: I will admit that I don’t love getting edits, but I try to think of them as problems to be solved: This is what I want to say; my editor is a smart reader, and she’s not understanding what I’m trying to do, as evinced by these edits; how can I fix the text to make her understand? Thinking that way takes my ego and its associated emotions out of the edits and helps me get the job done.

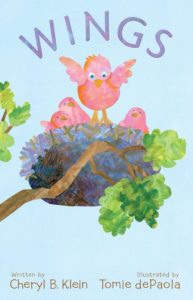

RVC: Tomie dePaola did the illustrations for your own picture book, Wings. What was it like working with an OMG illustrator?

CK: My editor for Wings was Emma Ledbetter of Atheneum/Simon & Schuster BFYR, now the editorial director at Abrams BFYR. She worked as Tomie’s in-house editor at Simon & Schuster, and she knew he loved birds, so she suggested him, and I was blown away by the mere idea of having him do the book. I of course envisioned his lovely, thick-lined, Strega Nona style at first—the one he’s best known for—and I was thrilled when I saw the new medium he used here: full-page-sized Avery labels, colored with markers and cut into shapes! It’s so simple, but in Tomie’s hands, so vibrant and artful, and perfect for the very elemental text. It’s been an honor and a pleasure, all the way around.

CK: My editor for Wings was Emma Ledbetter of Atheneum/Simon & Schuster BFYR, now the editorial director at Abrams BFYR. She worked as Tomie’s in-house editor at Simon & Schuster, and she knew he loved birds, so she suggested him, and I was blown away by the mere idea of having him do the book. I of course envisioned his lovely, thick-lined, Strega Nona style at first—the one he’s best known for—and I was thrilled when I saw the new medium he used here: full-page-sized Avery labels, colored with markers and cut into shapes! It’s so simple, but in Tomie’s hands, so vibrant and artful, and perfect for the very elemental text. It’s been an honor and a pleasure, all the way around.

RVC: Quite a few writers keep nudging me to ask agents and editors about what they do and don’t want. So let’s toss them a bone. Please offer up three specific things that just aren’t your cup of literary oolong.

CK: List manuscripts (that is, texts that are basically lists on a topic) that don’t build up to illuminate some underlying story or theme; rhyming texts with no sense of purpose, meter, or form; and scatological stuff. As much as kids love poop, pee, and fart jokes, I’m afraid I just say “Ew.”

RVC: I can’t help it—I’m a giver! So let’s give writers one more thing to chew on. What do you dream of finding in the slush pile?

CK: A manuscript by a diverse author illuminating a story from a contemporary kid’s life or a historical or scientific concept through their specific cultural lens, written to achieve some specific emotional effect, and pulling it off so well that I can’t wait to share it with everyone I know.

RVC: One last thing about your own work as a writer. What motivated you to create your own book on writing, The Magic Words?

CK: The Magic Words is a revision of my first, self-published book, Second Sight: Writing Great Books for Children and Young Adults, which was a collection of my SCBWI talks and personal blog posts and reflections on the art of writing. My motivation to write all of that material came in part from being asked to speak at various events, and in part from my longtime fascination with How Books Work, which dates back to my time as an English major in college. (I never went to grad school—I went into publishing instead—so my books on writing are kind of my attempt to do an M.A. on my own.) Still, maybe the thing I love most about great literature is that even when you take all the pieces apart as best you can—plot and theme and character and sound and so forth—there’s always some indefinable spark that can’t be captured: life, or truth, or anima, or soul … But I do love trying to capture it, and taking those pieces apart accordingly.

CK: The Magic Words is a revision of my first, self-published book, Second Sight: Writing Great Books for Children and Young Adults, which was a collection of my SCBWI talks and personal blog posts and reflections on the art of writing. My motivation to write all of that material came in part from being asked to speak at various events, and in part from my longtime fascination with How Books Work, which dates back to my time as an English major in college. (I never went to grad school—I went into publishing instead—so my books on writing are kind of my attempt to do an M.A. on my own.) Still, maybe the thing I love most about great literature is that even when you take all the pieces apart as best you can—plot and theme and character and sound and so forth—there’s always some indefinable spark that can’t be captured: life, or truth, or anima, or soul … But I do love trying to capture it, and taking those pieces apart accordingly.

RVC: Got a favorite takeaway or tip?

As for the best takeaways from The Magic Words, readers tend to love how practical the book is, so I’d point out the Character and Plot Checklists, which prompt readers to think about the essentials of both of those huge subjects as manifested in their own works-in-progress. I also place a strong emphasis on the fact that every writer is different, and no one writer’s technique is the One True Way That Will Work for Us All on Every Book—not even mine! But I offer a lot of options and directions to help each writer figure out their own True Way. And the closing essay on publishing puts forth one of my favorite similes: The submission process is as subjective and personal as dating, and to be approached rather like dating—with thoughtfulness about who you are, what your book is, and what you want out of the agent/editor/publishing relationship, and with a sense of humor as well.

RVC: Okay, it’s time to change things up. It’s time for … The OPB Speed Round! High-velocity Qs and As only, please. Are you ready?

CK: Bring it on!

RVC: What would be hardest to give up: social media or TV?

CK: Social media!

RVC: Stranger Things. Great Netflix original series, or the greatest Netflix original series?

CK: Great! (But I confess I only watched season one.)

RVC: You’re hosting an ice cream party for picture book characters, but you’ve only got the fixings for yourself plus three guests. Who joins you for double fudgie sundaes with extra strawberry sprinkles?

CK: Princess Pinecone and the Pony from Kate Beaton’s The Princess and the Pony (which I co-edited, I admit), and Lilly from Lilly’s Purple Plastic Purse. Lilly and Pinecone would get along famously, and the Pony and I would enjoy watching them as we ate all the ice cream.

CK: Princess Pinecone and the Pony from Kate Beaton’s The Princess and the Pony (which I co-edited, I admit), and Lilly from Lilly’s Purple Plastic Purse. Lilly and Pinecone would get along famously, and the Pony and I would enjoy watching them as we ate all the ice cream.

RVC: What’s the most recent picture book you signed? And using only three words, explain why you bought it.

CK: Unstoppable: Thirteen Adventures Alongside Athletes with Physical Disabilities, by Patty Cisneros Prevo. In three words: Energy! Inspiring! Diverse!

RVC: What’s the most underappreciated picture book of 2018?

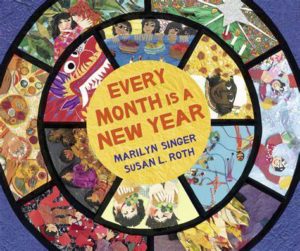

CK: Oh, man. My favorite (non-Lee & Low) picture book of the year was A Big Mooncake for Little Star by Grace Lin, but it received plenty of appreciation! I do wish more people had seen the Lee & Low book Every Month Is A New Year, by Marilyn Singer, with illustrations by Susan L. Roth, edited by my colleague Louise May. It’s a marvel of concept (the New Year’s celebrations that take place in each month of the year, somewhere around the world), research, poetry, illustration (all collage!), design, and backmatter.

CK: Oh, man. My favorite (non-Lee & Low) picture book of the year was A Big Mooncake for Little Star by Grace Lin, but it received plenty of appreciation! I do wish more people had seen the Lee & Low book Every Month Is A New Year, by Marilyn Singer, with illustrations by Susan L. Roth, edited by my colleague Louise May. It’s a marvel of concept (the New Year’s celebrations that take place in each month of the year, somewhere around the world), research, poetry, illustration (all collage!), design, and backmatter.

RVC: Best compliment you’ve ever received?

CK: Can I cite two—one professional, one personal? Sherry Thomas, a novelist I work with, said, “I didn’t think editors edited like this anymore” after we finished her book. And J. K. Rowling told me that I looked like Gwyneth Paltrow!

RVC: Thanks so much, Cheryl!

This month’s Industry Insider Interview is with Lee

This month’s Industry Insider Interview is with Lee