This month’s Industry Insider interview is with Deidra Purvis, an Acquisitions Editor for Free Spirit Publishing, an imprint of Teacher Created Materials. Free Spirit is the “leading publisher of social and emotional learning books for kids, teens, and educators.” The press also notes that it’s “unabashedly pro-kid.” Love that, right?

This month’s Industry Insider interview is with Deidra Purvis, an Acquisitions Editor for Free Spirit Publishing, an imprint of Teacher Created Materials. Free Spirit is the “leading publisher of social and emotional learning books for kids, teens, and educators.” The press also notes that it’s “unabashedly pro-kid.” Love that, right?

Prior to her job as an editor, she spent a lot of time as a classroom teacher and Director of Classroom Services for a book distributor. Don’t worry—we’ll ask about all of that in a moment!

In her free time, Deidra writes creative nonfiction, backpacks, gardens, and rides a bicycle.

Let’s jump to the interview to learn more about Deidra!

RVC: What kind of childhood did you have, and how did it pave the way for your kidlit career?

DP: My childhood was pretty amazing in that I was surrounded by people who loved me.

RVC: I love interviews that start like this!

DP: I grew up in a low-income household in rural Ohio, and I lived close to the land—I always loved nature and animals, and one of my favorite things was mushroom hunting in the woods with my dad every spring. Most of the men who immediately surrounded me also battled with alcohol use disorder, and that impacted me a lot. I grew up very insecure about my weight and other aspects of my body, and that became one of my biggest challenges. I also worried a lot about money.

I was very quiet, but I always had a lot of thoughts that I wanted to share and needed to process. I started journaling when I was around 10 years old to have an outlet for expressing everything that was bottled up in my head, and it grew my love for writing. This all developed an interest in mental health, too. I started reading books about mindfulness and practicing meditation when I was in middle and high school. The books I started reading around that age were intended for adults; and it’s funny looking back and thinking about how much I could have used books by Free Spirit when I was a kid and teenager. My interest in books, writing, and SEL all grew from my childhood.

RVC: So many writers end up writing books they wanted/needed as kids. It makes total sense. Now, what were some of the formative books you read during those early years?

DP: I had a small bookshelf in my room, and I’d read these picture books on repeat: Happy Birthday Moon by Frank Asch, I Wear My Tutu Everywhere by Wendy Cheyette Lewison, Corduroy by Don Freeman, and The Monster at the End of This Book by Jon Stone.

DP: I had a small bookshelf in my room, and I’d read these picture books on repeat: Happy Birthday Moon by Frank Asch, I Wear My Tutu Everywhere by Wendy Cheyette Lewison, Corduroy by Don Freeman, and The Monster at the End of This Book by Jon Stone.

RVC: What a great list!

DP: My mom had a great reading voice, and that’s what drew me to a lot of these books. I remember loving the way she made the echoing noise when the moon would speak, and I remember how dramatic she was when reading Grover’s voice in The Monster at the End of this Book. But I think it’s mostly by chance that these are the books I ended up with. They were all hand-me-downs other than the tutu book, and it’s funny because I was never a girly girl or into tutus.

As an older kid, my favorite book was Anne of Green Gables by Lucy Maud Montgomery. Then I started reading more and more nonfiction. Somewhere around late elementary, I wanted to work with animals, so I would go to the library and check out stacks of nonfiction books about animals. Then I got into books about meditation and memoirs.

As an older kid, my favorite book was Anne of Green Gables by Lucy Maud Montgomery. Then I started reading more and more nonfiction. Somewhere around late elementary, I wanted to work with animals, so I would go to the library and check out stacks of nonfiction books about animals. Then I got into books about meditation and memoirs.

RVC: Clearly, the plan for college was to learn to be a K‑12 teacher. What about that career choice appealed to you?

DP: I wanted to be a teacher for two reasons. It was important to me to follow a career path that made a positive impact in the world. I didn’t want take part in a career that I felt was harming people or the planet—I wanted to do good.

RVC: If only more people had such a goal!

DP: Teaching felt like the most impactful career that I could have. I also loved writing, but I didn’t think writing or working in publishing was realistic. I decided the best path for me was to be an English teacher.

RVC: How did the teaching go?

DP: Teaching was hard, so hard. It ended with me wearing my body down and getting very sick. I still believe that teaching is one of the most important careers possible. I loved my students and had so many rewarding moments with them. If I could make one change in the world, I wish teachers had more support in doing the important work that they do.

RVC: Having been a teacher for 25 years, I quite agree. So, you moved into a non-classroom role fairly soon after college. What kinds of things did you do as Director of Classroom Services?

DP: This was such a great move for me! I started calling myself a professional book nerd.

RVC: Love that term!

DP: I was part of a team of former teachers who had the job of curating custom book lists for PK-12 classrooms across the U.S., and I eventually was promoted to be the director of this department. Each season, reps from all the major publishers would present their newly released children’s books to us, and they’d leave samples for us to review. This is what really grew my love for picture books.

Teachers, principals, librarians, and school district contacts would then reach out to my team with specific book needs. For example, a school principal might reach out to us and tell us they wanted to buy classroom libraries for every classroom in the building for grades K‑5. I would ask them questions to get to know the needs and interests of the students I would be serving, and I would use that information to curate custom classroom libraries for each teacher, specifically for their students. Making sure the students in the classroom could see themselves reflected in the books they had access to was important to me, and it showed me how far the book industry still needs to go to allow this to be possible. This job really gave me a look into the market, where the needs were, and where there were gaps. Most importantly, though, it really made me fall in love with kidlit.

RVC: A few years after your undergrad degree, you went back to school for an MFA in creative writing from Hamline. What was the goal?

DP: My goal at Hamline was to spend time doing what I loved doing. I had a vague goal of eventually getting a job in publishing so I could pursue what I loved, but my primary goals were to enjoy my time doing what I loved, to learn as much as possible about the craft, and to be around other writers.

RVC: What was the most useful thing your Hamline experience taught you?

DP: Wow. Everything. I’m happy that I studied fiction, creative nonfiction, and poetry. It really gave me knowledge into all forms of writing that I apply to my job today. I also spent a lot of time with Water~Stone Review, an annual literary journal published by Hamline University. In one class, I served on the editorial board for the journal. We read the final submissions that were being considered for publication and held conversations about which pieces should be published in the journal. This is where I learned how to read as an acquiring editor—How do you decide if something is ready to be published? What qualities do you look for? During my time at Hamline, in addition to serving on this editorial board, I also contributed as a screener for a couple years, and I was Assistant Editor of Creative Nonfiction during my last year at Hamline. Working on Water~Stone Review ultimately taught me the skills I needed to become an acquiring editor. I wouldn’t be here without it.

RVC: I’m a big fan of college literary magazines for exactly this reason–it’s such good training. How did you end up at Free Spirit?

DP: The stars aligned, and I still pinch myself when I reflect on how much I love my job and how I ended up here. My seven years curating and selling custom book lists kept me more engaged in education than I’d ever been before. I had the opportunity to attend annual conferences from organizations like ASCD, ILA, and NCTE. I was talking with leaders in education across the U.S. on a daily basis, so I became really in tune with new research in pedagogy; and, like I said, I came to know the kidlit book market really well.

I also had a personal interest in social and emotional learning (SEL) that started developing way back in my childhood, so when I learned more about school districts implementing SEL, I knew I wanted that to be my focus. I was often tasked with recommending book lists aligned with SEL units; I would research and incorporate SEL in the blogs I would write; and I would also present professional learning webinars through an SEL lens whenever I had the chance. I was so excited about the work being done in schools around SEL that I was considering possibly going back into the classroom if I couldn’t get into publishing.

But then it all came together. I had experience as a teacher, I knew the kidlit market, I was finishing up my MFA in Creative Writing, and I had a special interest in SEL. I was already a fan of Teacher Created Materials (TCM) because I regularly recommended their books to teachers, so when I saw their job posting for acquiring editor for Free Spirit, TCM’s imprint founded forty years ago to provide kids with social emotional resources, it was like the job description was written for me, and I had to go after it.

RVC: What’s the first picture book you acquired while there?

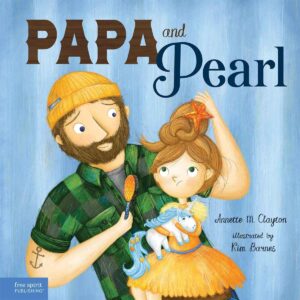

DP: The first picture books that I acquired will be available this summer. Two that I’m most excited for are Papa and Pearl by Annette M. Clayton and illustrated by Kimberley Barnes and Sonia and the Super-Duper Disaster by Rachel Funez and illustrated by Kelly Kennedy.

DP: The first picture books that I acquired will be available this summer. Two that I’m most excited for are Papa and Pearl by Annette M. Clayton and illustrated by Kimberley Barnes and Sonia and the Super-Duper Disaster by Rachel Funez and illustrated by Kelly Kennedy.

RVC: What about each of these books appealed to you as acquiring editor?

DP: Papa and Pearl is a sweet story about a father and daughter immediately following the divorce of Pearl’s parents. It’s full of imagery related to princesses, pirates, and mermaids. What appealed to me about this story was that Annette M. Clayton’s writing is lyrical and imaginative. It’s a fun book any child will love, and it’s also a helpful resource for children experiencing the separation of their parents.

RVC: And what about the other one?

DP: Sonia and the Super-Duper Disaster by Rachel Funez is about a girl who realizes she forgot her mom’s birthday, so she decides to whip up a last-minute super-duper surprise in the kitchen. Sonia has ADHD and anxiety, and throughout the story, she uses strategies to manage challenges as they arise. This one is filled with superhero imagery, and it’s another story that any child can love. It’s hilarious, and it’s also a great resource to demonstrate specific strategies children can use to manage anxiety that may pop up in their own lives.

RVC: I get the sense that Free Spirit’s picture books are different than those by, say, Candlewick, Peachtree, or other kidlit presses.

DP: All of the resources you’ll find in Free Spirit’s catalog are intended to help children and teens think for themselves, overcome challenges, and make a difference in the world. You can use our books to tackle tough topics such as neurodiversity, anger and stress management, childhood and teenage depression, anxiety, grief and loss, and gender. We have a growing list of picture books like ones that you would see in Candlewick or Peachtree’s catalogue. They are high interest,  engaging, lyrically written, and include elements of fun and humor–and they cover a broad range of issues important to kids—from celebration of identity and family to tough topics like anxiety and grief. A good example of a Free Spirit book is Paula’s Patches by Gabriella Aldeman and illustrated by Rocío Arreola Mendoza, about a girl who is embarrassed when her hand-me-down pants rip at school. She comes up with a creative solution of making patches not only for herself, but to share with her friends as well. The book is an authentic and fun exploration of problem solving.

engaging, lyrically written, and include elements of fun and humor–and they cover a broad range of issues important to kids—from celebration of identity and family to tough topics like anxiety and grief. A good example of a Free Spirit book is Paula’s Patches by Gabriella Aldeman and illustrated by Rocío Arreola Mendoza, about a girl who is embarrassed when her hand-me-down pants rip at school. She comes up with a creative solution of making patches not only for herself, but to share with her friends as well. The book is an authentic and fun exploration of problem solving.

We include that element of fun and humor in our books even when tackling tough topics. This aspect is really front and center in our new release You Made Fun of My Sandwich by Jessica Pegis and illustrated by Harry Briggs. It is laugh out loud funny, and I love the speaker’s inquisitive voice. It starts with a child’s observation that a classmate is mocking their sandwich, and then we follow the child’s imaginative and hilarious thought process as they consider why. As fun as this book is for children to read, it tackles two tough topics: bullying and hunger.

We include that element of fun and humor in our books even when tackling tough topics. This aspect is really front and center in our new release You Made Fun of My Sandwich by Jessica Pegis and illustrated by Harry Briggs. It is laugh out loud funny, and I love the speaker’s inquisitive voice. It starts with a child’s observation that a classmate is mocking their sandwich, and then we follow the child’s imaginative and hilarious thought process as they consider why. As fun as this book is for children to read, it tackles two tough topics: bullying and hunger.

Another thing that really sets our list apart is that we seek out experts in children’s mental health for many of our books. Our picture book What Does Grief Feel Like? is written by Dr. Korie Leigh who has specialized in working with children and families experiencing grief and loss for over 16 years. When you read a Free Spirit book, you can trust that the representation, strategies, and tools are backed by experts. You can also trust that we’re addressing both these topics in an engaging kid-friendly way.

Another thing that really sets our list apart is that we seek out experts in children’s mental health for many of our books. Our picture book What Does Grief Feel Like? is written by Dr. Korie Leigh who has specialized in working with children and families experiencing grief and loss for over 16 years. When you read a Free Spirit book, you can trust that the representation, strategies, and tools are backed by experts. You can also trust that we’re addressing both these topics in an engaging kid-friendly way.

RVC: What’s the biggest misconception about SEL (social and emotional learning) picture books?

DP: Some people might think that SEL picture books are didactic and can only be used to teach emotions or other SEL skills or strategies. My favorite SEL picture books are the ones that tell authentic stories using rich language and engaging artwork. Any child or adult can fall in love with them, and they don’t have to read it for the SEL element. I also think that most good picture books are SEL picture books. We read books to learn about ourselves and the world, to feel a sense of belonging, to celebrate identity, to see how characters navigate challenges, or to build appreciation and joy. All of these are qualities of SEL picture books.

RVC: As an acquiring editor, who or what has most influenced you?

DP: My childhood influenced me a lot, and I continue to be inspired by the children around me. I also have to shout out the editors at Free Spirit. They are so talented and do amazing work. I’ll often peek into the manuscripts they’re working on, and I’m in awe of their thoughtful feedback to the authors they work with. It’s such a gift that I get to learn from them every day. It’s another reason I sometimes pinch myself—I’m surrounded by a lot of talent here at Free Spirit.

RVC: You’re a writer, too. What kind of creative nonfiction are you making?

DP: I’m working on memoir that I hope to start sending out to agents and editors within the next year. I also have several essays and poems on submission with literary journals. Almost everything I write is in exploration of my childhood in rural Ohio.

RVC: Any interest in writing picture books of your own?

DP: For sure. It’s not something I’m actively working on, but the temptation is there.

RVC: Since COVID, I’ve been asking everyone at least one health and wellness question. How do you defeat negativity—either internally or from outside yourself?

DP: Learning loving-kindness meditation was a gamechanger for me.

RVC: One final question for this part of the interview. What upcoming book are you especially excited about?

DP: The next Free Spirit book that I’m really looking forward to is Dominique’s Thrifted Treasures by Margarett McBride and illustrated by Ryan Middaugh. Please read it because it’s doing exactly what I said I love about SEL picture books. It’s a beautiful story that highlights community and shared experiences. Dominique receives a hand-me-down jacket from their Pawpaw and isn’t too enthused. However, after Mama comes home with a bag of thrifted clothes from the thrift store the next day, Dominique becomes fascinated by the unique story of each piece of clothing. They spend the day running errands with Pawpaw and running into people who previously owned each item Dominique is wearing. Thrifting is such a fun and relevant topic, and the idea of appreciating the community aspect of thrifting and the stories that the clothes tell is so touching. The artwork is beautiful, and I can’t wait to see this book in the world. It will be available in February 2024.

DP: The next Free Spirit book that I’m really looking forward to is Dominique’s Thrifted Treasures by Margarett McBride and illustrated by Ryan Middaugh. Please read it because it’s doing exactly what I said I love about SEL picture books. It’s a beautiful story that highlights community and shared experiences. Dominique receives a hand-me-down jacket from their Pawpaw and isn’t too enthused. However, after Mama comes home with a bag of thrifted clothes from the thrift store the next day, Dominique becomes fascinated by the unique story of each piece of clothing. They spend the day running errands with Pawpaw and running into people who previously owned each item Dominique is wearing. Thrifting is such a fun and relevant topic, and the idea of appreciating the community aspect of thrifting and the stories that the clothes tell is so touching. The artwork is beautiful, and I can’t wait to see this book in the world. It will be available in February 2024.

RVC: Alright, Deidra. It’s time for the LIGHTNING ROUND. I’ll zip out some questions and you zap back some answers. Are you ready?

DP: Sure!

RVC: Would you rather have a personal chef, a maid, or a masseuse?

DP: A personal chef, please!

RVC: What inanimate object would be the worst if it played loud dance music every time it was used?

DP: A pillow?

RVC: What’s the funniest word in the English language?

DP: Lollygag? I don’t know if I think any word is funny, but lollygagging brings me joy.

RVC: Your life is on the line. You need to sing one karaōke song to save it. What do you go with?

DP: “Bicycle Race” by Queen.

RVC: What’s the last SEL picture book you read that WOWed you?

DP: So hard! I have a lot of favorites, but the most recent one I read that really moved me was A Day with No Words by Tiffany Hammond.

DP: So hard! I have a lot of favorites, but the most recent one I read that really moved me was A Day with No Words by Tiffany Hammond.

RVC: Let’s end with your favorite line from any Free Spirit picture book.

DP: I love the opening lines from I Think I Think A Lot by Jessica Whipple: “I think. I think a lot. I think I think a lot.” Such a cute, relatable, and important book.

RVC: Thanks so much, Deidra!

I do not agree with you “that there are some elements good stories need, like conflict and tension, that keeps the story moving and the reader reading.” I see this all the time in craft books and I disagree. Many cultures do not tell stories this way. Yet, they tell amazingly good stories. We cannot dismiss stories because it doesn’t follow the standards of whiteness. We have to respect cultures and embrace those cultures and their style of storytelling. This is why we are at the point in publishing where there’s a need and cry for “diverse books and stories.” Authentic storytelling is not one way, it isn’t a cookie-cutter narrative. Authentic storytelling is how that culture tells stories and what stories they deem necessary to be told. And I would hope that others would want to experience how different cultures document their stories.

I do not agree with you “that there are some elements good stories need, like conflict and tension, that keeps the story moving and the reader reading.” I see this all the time in craft books and I disagree. Many cultures do not tell stories this way. Yet, they tell amazingly good stories. We cannot dismiss stories because it doesn’t follow the standards of whiteness. We have to respect cultures and embrace those cultures and their style of storytelling. This is why we are at the point in publishing where there’s a need and cry for “diverse books and stories.” Authentic storytelling is not one way, it isn’t a cookie-cutter narrative. Authentic storytelling is how that culture tells stories and what stories they deem necessary to be told. And I would hope that others would want to experience how different cultures document their stories. The takeaway message to self-published authors is to spend a lot of time and thought putting your book together. The Churchmans [a couple who self-published] looked at formats and chose the largest trim size that could fit comfortably on standard shelves. They printed the book on 100lb paper—heavier stock than most traditional publishers can use—and also used extra heavy board for the hardcover case. They hired an editor to help them shape the text. And they mounted a Kickstarter campaign to fund their upfront costs. They took a lot of care.

The takeaway message to self-published authors is to spend a lot of time and thought putting your book together. The Churchmans [a couple who self-published] looked at formats and chose the largest trim size that could fit comfortably on standard shelves. They printed the book on 100lb paper—heavier stock than most traditional publishers can use—and also used extra heavy board for the hardcover case. They hired an editor to help them shape the text. And they mounted a Kickstarter campaign to fund their upfront costs. They took a lot of care. I’m most likely to pass on rhyming picture books or picture books that cover ground that’s well-trod (alphabet books, goodnight books). That’s both personal taste and a business decision. For example, it’s extremely hard to pull off rhyme. And in a market flooded with “goodnight” books, it can be hard to make another one stand out in the crowd. Also, just as a matter of personal taste, I don’t like treacly-sweet “I love you” books.

I’m most likely to pass on rhyming picture books or picture books that cover ground that’s well-trod (alphabet books, goodnight books). That’s both personal taste and a business decision. For example, it’s extremely hard to pull off rhyme. And in a market flooded with “goodnight” books, it can be hard to make another one stand out in the crowd. Also, just as a matter of personal taste, I don’t like treacly-sweet “I love you” books. First, when I started in children’s publishing, we were just beginning to see books like Harry Potter,

First, when I started in children’s publishing, we were just beginning to see books like Harry Potter,  People in children’s book publishing are often drawn to this industry, at least in part, because it offers a chance to do something meaningful and positive in the world. I think it’s safe to say that with the start of the Trump administration, many acquiring editors feel uniquely positioned to help counter some of the policies or currents of opinion—about immigrants, about diversity, about

People in children’s book publishing are often drawn to this industry, at least in part, because it offers a chance to do something meaningful and positive in the world. I think it’s safe to say that with the start of the Trump administration, many acquiring editors feel uniquely positioned to help counter some of the policies or currents of opinion—about immigrants, about diversity, about

I can tell from the first page if I want to read on. I tag as I look through things: yes, no, further investigation needed. I am looking for specific stories now and specific writing qualities. If it is something I might be interested in, I give it three chapters. I need to be compelled in three chapters or I pass. After that, if I am still interested, I request. Once a full manuscript comes in, I read it with an eye for how much work it will need, and if I have a vision or feel compelled. I have perfectly lovely manuscripts that I pass on because I just didn’t find that passion. And passion drives the ship. When you are neck deep in 13 passes from editors, you want to feel that spark of joy that makes you say, “Screw this, I know I am right.”

I can tell from the first page if I want to read on. I tag as I look through things: yes, no, further investigation needed. I am looking for specific stories now and specific writing qualities. If it is something I might be interested in, I give it three chapters. I need to be compelled in three chapters or I pass. After that, if I am still interested, I request. Once a full manuscript comes in, I read it with an eye for how much work it will need, and if I have a vision or feel compelled. I have perfectly lovely manuscripts that I pass on because I just didn’t find that passion. And passion drives the ship. When you are neck deep in 13 passes from editors, you want to feel that spark of joy that makes you say, “Screw this, I know I am right.” I think as writers we often forget how many plates agents have to spin and that most agents still need a day job to survive financially. Being on the other side of things helped me understand timing and what goes into deciding what projects to represent. While there are so many wonderful stories out there that I may fall in love with, there’s also an element of how I can make this book great and if I can sell it. Oftentimes, as writers we idolize the idea of getting an agent and forget that it is a business partnership as well. The reason why it takes so long for agents to get back to writers right away is because clients come first and it takes time to read, to make sure the project will be the right partnership. That being said, I wish I knew how much went into agenting before I started querying because now a rejection isn’t something I worry about and I understand if it takes long, it actually might be a good thing. It’s all about patience, right timing and working on your craft in the meantime.

I think as writers we often forget how many plates agents have to spin and that most agents still need a day job to survive financially. Being on the other side of things helped me understand timing and what goes into deciding what projects to represent. While there are so many wonderful stories out there that I may fall in love with, there’s also an element of how I can make this book great and if I can sell it. Oftentimes, as writers we idolize the idea of getting an agent and forget that it is a business partnership as well. The reason why it takes so long for agents to get back to writers right away is because clients come first and it takes time to read, to make sure the project will be the right partnership. That being said, I wish I knew how much went into agenting before I started querying because now a rejection isn’t something I worry about and I understand if it takes long, it actually might be a good thing. It’s all about patience, right timing and working on your craft in the meantime. A big part of this process for me is trying to make sure that the surface story and takeaway are strong enough to catch an editor’s attention and enable them to see the bigger picture. I’m not an editor in the way that your editor, Frances Gilbert, is and she will definitely make

A big part of this process for me is trying to make sure that the surface story and takeaway are strong enough to catch an editor’s attention and enable them to see the bigger picture. I’m not an editor in the way that your editor, Frances Gilbert, is and she will definitely make

I always ask myself whether this is something children actually

I always ask myself whether this is something children actually  I’m open [to self-published or indie authors] so long as the project they’re querying hasn’t already been published. Those I won’t take on because the project really needs to be an Indie bestseller in order for editors to consider it. Otherwise it doesn’t really matter to me unless those projects are problematic/poorly written. My general advice is don’t try to use self-publishing as a way to launch yourself into traditional publishing. It backfires more often than it works.

I’m open [to self-published or indie authors] so long as the project they’re querying hasn’t already been published. Those I won’t take on because the project really needs to be an Indie bestseller in order for editors to consider it. Otherwise it doesn’t really matter to me unless those projects are problematic/poorly written. My general advice is don’t try to use self-publishing as a way to launch yourself into traditional publishing. It backfires more often than it works. If I’m intrigued, I send insights about areas to revise. I don’t want to hear back in, like, two hours because I don’t believe the writer will have really pondered and had opportunity to decide whether the revisions seem like a direction that feels right. But I also want to hear back in some reasonable amount of time (a few months would be really long for a picture book, unless my thoughts for revision would have major impact on illustrations for an author/illustrator).

If I’m intrigued, I send insights about areas to revise. I don’t want to hear back in, like, two hours because I don’t believe the writer will have really pondered and had opportunity to decide whether the revisions seem like a direction that feels right. But I also want to hear back in some reasonable amount of time (a few months would be really long for a picture book, unless my thoughts for revision would have major impact on illustrations for an author/illustrator). I particularly love what I call “historical footnote” picture books, that build a story around lesser known bits from history. I’m also looking for picture books that capture ordinary or natural moments that feel like they’re magical—moments like capturing fireflies, bread dough rising, watching a bird murmuration, the Northern Lights, planting a seed and having it grow into a living plant, and so on. We’re surrounded by ordinary magic, and I want to celebrate it! I’m also particularly looking for picture books that explore something peculiar that happens in nature.

I particularly love what I call “historical footnote” picture books, that build a story around lesser known bits from history. I’m also looking for picture books that capture ordinary or natural moments that feel like they’re magical—moments like capturing fireflies, bread dough rising, watching a bird murmuration, the Northern Lights, planting a seed and having it grow into a living plant, and so on. We’re surrounded by ordinary magic, and I want to celebrate it! I’m also particularly looking for picture books that explore something peculiar that happens in nature. One interesting thing is that independent booksellers have been compelled to be so much more nimble and creative to stay competitive and so many of them have gotten really good at selling picture books and middle-grade books.

One interesting thing is that independent booksellers have been compelled to be so much more nimble and creative to stay competitive and so many of them have gotten really good at selling picture books and middle-grade books. I regularly see picture book biography texts that are well done but just don’t completely grab me. A common problem with these is pacing. Everything in the subject’s life is given equal weight, so the highs don’t feel all that high nor do the lows feel all that low.

I regularly see picture book biography texts that are well done but just don’t completely grab me. A common problem with these is pacing. Everything in the subject’s life is given equal weight, so the highs don’t feel all that high nor do the lows feel all that low. Communication is key!!! It’s so important to me that my clients feel comfortable talking to me about any concerns they have throughout the process. I am always here! Most authors will feel a range of emotions throughout the submission process and beyond. Are you feeling disheartened? Would you like to talk strategy? Do you have editors you’d like me to submit to? Are you confused about contract language or what something means? I am always open to suggestions as well. It’s a partnership! Every author is different as far as how often they want to communicate and in what way (phone, email, etc.) and how involved they want to be in particular aspects of the process. So, I always like to be as clear on those details as possible. I want everyone I work with to be happy, know that I have their back, and be comfortable talking through things with me.

Communication is key!!! It’s so important to me that my clients feel comfortable talking to me about any concerns they have throughout the process. I am always here! Most authors will feel a range of emotions throughout the submission process and beyond. Are you feeling disheartened? Would you like to talk strategy? Do you have editors you’d like me to submit to? Are you confused about contract language or what something means? I am always open to suggestions as well. It’s a partnership! Every author is different as far as how often they want to communicate and in what way (phone, email, etc.) and how involved they want to be in particular aspects of the process. So, I always like to be as clear on those details as possible. I want everyone I work with to be happy, know that I have their back, and be comfortable talking through things with me. A picture book is more than anything else a piece of theater, with pictures and words unfolding together as the pages turn and turn and turn all the way to that most important and satisfying one—the final turn from pages 30–31 to page 32.

A picture book is more than anything else a piece of theater, with pictures and words unfolding together as the pages turn and turn and turn all the way to that most important and satisfying one—the final turn from pages 30–31 to page 32. Three hundred and fifty words is definitely on the short end of the picture books we publish! Word counts can vary greatly depending on things like the age group they’re targeting, and whether they’re fiction or nonfiction.

Three hundred and fifty words is definitely on the short end of the picture books we publish! Word counts can vary greatly depending on things like the age group they’re targeting, and whether they’re fiction or nonfiction. In terms of process, it’s [writing a picture book] sort of a cross between composing a poem and writing a short essay. For many years I did a column for

In terms of process, it’s [writing a picture book] sort of a cross between composing a poem and writing a short essay. For many years I did a column for  If I knew the formula for making a finished book irresistible, I would be a millionaire. Even after years of experience, I find it hard to anticipate which titles will really take off. I always pause when I have the first bound book in my hands and celebrate that achievement. What the market thinks is out of our control. Nevertheless, most bookstores use the top seasonal holidays as a hook for a display. Back to school is another important season for picture books. It goes without saying, that the publisher has priced the book competitively and the trim size is right for the story, i.e. some books are “lap books” that can be spread across the laps of two readers; some illustrations call for vertical size and others for landscape.

If I knew the formula for making a finished book irresistible, I would be a millionaire. Even after years of experience, I find it hard to anticipate which titles will really take off. I always pause when I have the first bound book in my hands and celebrate that achievement. What the market thinks is out of our control. Nevertheless, most bookstores use the top seasonal holidays as a hook for a display. Back to school is another important season for picture books. It goes without saying, that the publisher has priced the book competitively and the trim size is right for the story, i.e. some books are “lap books” that can be spread across the laps of two readers; some illustrations call for vertical size and others for landscape. So what does it mean to have a book for kids aged 3–7? It means that you need to focus on things these children can understand and can relate to. Keep in mind what a young kids’ experience with the world is and what is interesting to them. A four-year-old isn’t going to want to read a book about a ten-year-old. They can’t relate to what that character is going through and probably won’t understand the book. Young children are still learning how the world works and wont usually comprehend more complex emotional stories. That’s why most picture books tend to be simplified. A book about bullying, for example, would likely focus on a protagonist stepping up to stop the bullying, not the actual physical and emotional abuse the bullied child experiences.

So what does it mean to have a book for kids aged 3–7? It means that you need to focus on things these children can understand and can relate to. Keep in mind what a young kids’ experience with the world is and what is interesting to them. A four-year-old isn’t going to want to read a book about a ten-year-old. They can’t relate to what that character is going through and probably won’t understand the book. Young children are still learning how the world works and wont usually comprehend more complex emotional stories. That’s why most picture books tend to be simplified. A book about bullying, for example, would likely focus on a protagonist stepping up to stop the bullying, not the actual physical and emotional abuse the bullied child experiences. Welcome to this month’s Industry Insider guest, Taylor Norman, a rock star in the realm of children’s literature as Executive Editor at Neal Porter Books/Holiday House. Let’s give her a big, warm welcome!

Welcome to this month’s Industry Insider guest, Taylor Norman, a rock star in the realm of children’s literature as Executive Editor at Neal Porter Books/Holiday House. Let’s give her a big, warm welcome!

Welcome to Meredith Mundy, the Editorial Director at Abrams Appleseed. With a career spanning over two decades, Meredith’s keen eye for quality has helped discover and nurture many talented authors and illustrators. Her work on everything from an

Welcome to Meredith Mundy, the Editorial Director at Abrams Appleseed. With a career spanning over two decades, Meredith’s keen eye for quality has helped discover and nurture many talented authors and illustrators. Her work on everything from an

Here’s Sandra’s wonderful mission statement to give us a glimpse into the soul of Gnome Road:

Here’s Sandra’s wonderful mission statement to give us a glimpse into the soul of Gnome Road: