This month’s PB author interview is by a writer who has a special relationship with OPB—she helped get it going. I’d been mulling over creating this website for a few years and when I shared the idea with my friend and mentor, Jane Yolen, she told me: “Silly boy. Why aren’t you already doing this?”

This month’s PB author interview is by a writer who has a special relationship with OPB—she helped get it going. I’d been mulling over creating this website for a few years and when I shared the idea with my friend and mentor, Jane Yolen, she told me: “Silly boy. Why aren’t you already doing this?”

So, of course, I did exactly that. And she was eager to volunteer to be one of my first interviewees. The only reason she wasn’t the first one published here? I had many hours of recordings to work through and I’m a slow transcriber. Plus—what to leave out? What to include? It wasn’t easy.

I was lucky enough to be able to bring Jane out to Ringling College of Art and Design in January 2018 for a couple of days of events to support the creative writing program there. So the following interview has been pieced together from just a small bit of the mountain of writing and publishing information she shared in classes, student meetings, lunchtime talks, and public evening discussions. Yes, this is longer than most OPB author interviews but I suspect you’ll forgive me for its length. (And if you still need more from Jane, check out my interview with her in a fall 2018 issue of The Writer, where I cover lots of different things than what’s below.)

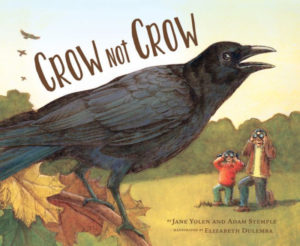

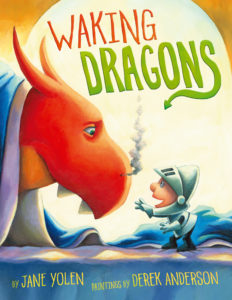

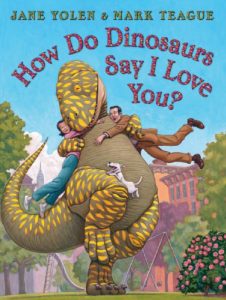

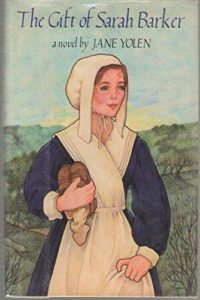

Jane really needs no introduction. If you’re here, you love picture books. If you love picture books, you surely have a half-dozen favorites written by her. I’ll simply end this warm-up by sharing three of my own favs of hers. If you don’t have these already, maybe grab a copy?

RVC: One of your Ten Rules for Writing Success is BIC. Could you share what that is?

JY: Butt in Chair. Or if you wish to be polite here in Florida—Bottom, Buttocks, Behind, Backside, Behunkus in Chair.

In other words, you have to work. Fingers on keys. Or wrapped around a pen. Use a chisel to carve the book on stone. If you aren’t at work writing, you’re not writing the book.

Yes, there are other parts to writing. There’s thinking it through. There’s research. There’s seeing landscape. There’s listening in keyholes. There’s sorting through gossip. There’s smelling the grandbabies. These are all wonderful parts of getting ready to write. They’re what I call “gathering days.”

But in the end, if you never put your B in the C, you are not going to write the damn book.

RVC: Procrastination really isn’t part of your vocabulary, is it?

JY: You see, too often we sit around thinking about what we hope to, plan to, want to write … and never do. The difference between my 366 books and your not-quite one, or not-quite five or not-quite ten or even your not-quite 100 books is as simple as that. Write the damn book.

Stop agonizing over whether you’re an undergraduate or a graduate student, a housewife or somebody’s younger brother. Stop worrying about having original ideas or contracts or contacts. Stop telling your boyfriend or girlfriend or spouse or partner that some day soon they’ll see you in print.

Just write the damn book.

Now I’ve just said “damn” three times. Oops—make that four times. If that seems unseemly for a children’s book writer, I apologize. But choosing and using the right word has been my passion for over 50 years now. (Longer if you add in my writing in high school and elementary school, though some of it was pretty lame, I admit.) And damn is the right word. Though one famous children’s book writer friend of mine calls it something stronger, from earlier on in the alphabet, which I won’t use here in polite company.

I know that urging—no insisting—that you write the damn book may seem simplistic. But until you get the book down, what have you to show?

I was an editor for fifteen years, and editors know that finishing a book is one of the hardest parts of writing. Most would-be writers want to have written. But for true writers, it’s the process of writing that they find fulfilling, not necessarily publication.

For years over my desk, I had posted: “Love the process, not the product” and while I have long since lost that piece of paper, I no longer need it. That motto is imprinted on my heart.

Yes, I know. Easy for me to say with my 365th and 366th book just out this past March, but honestly, that number could’ve been a terrible burden if I didn’t love writing. The writing—even when it is difficult, even when it’s horrible, even when it’s going badly—is the reason for doing what we do.

So that’s why my very first rule has to be: Write the damn book!

RVC: For some years now, you’ve run small writing workshops—called Picture Book Boot Camps—that are described as “A weekend Master Class for published picture book authors with Jane Yolen, held at her farm in western Massachusetts.” Where did the idea for these retreats come from?

JY: For years, I taught workshops at writer’s conferences and weekend retreats, and I loved the teaching, but when someone else is throwing the party, they get to keep all the change. So to do a 2- or 3- or 10-day conference? Putting what I’m writing on hold for that many days for nearly any amount of money became non-doable.

When we put together a conference of our own, Heidi [Jane’s daughter Heidi EY Stemple, who is an accomplished PB writer too] and I make enough money to make it worthwhile and we plan it exactly the way we want to. I’m still able to do some of my own work during the Boot Camps, too.

We’ve had some absolutely stunning authors participate and their work was extraordinary at times. We’re working with people who are already published and that was a very conscious choice. We wanted people who already understood what revision meant, people who understood what listening to critique—without pride or arguing—meant, people who listened when you talked about problems and went on to solve them in their own way.

I get a lot of people asking: “When are you going to do a picture book boot camp for newbies”? And my answer is never. There are lots of places that will do that, like an SCBWI conference where people can have their first manuscript read by a professional in the field. That’s not what I’m going to do here.

“Can’t you do a boot camp for novelists?” people also ask. For nine years, I edited novels. But to really be able to provide a good and solid critique of a novel, reading one chapter isn’t enough. You really need to read the whole thing.

How could I possibly read 10 whole novels like that? I’d have to put my entire life on hold to sit down and write the kind of critiques I’d like to provide as an editor.

RVC: One of the things you told my Writing Picture Book students is to cultivate patience. I’ve been thinking about that myself a good bit these days.

JY: There are two kinds of patience needed when working on any kind of writing.

The first is with yourself. Give yourself the time you need to settle into your story, to find your characters who—like recalcitrant teenagers—sometimes want to be anywhere but where you are. Or your poem, with its fish-sliding words that are difficult to catch. Or your essay or memoir or anything.

And more, you need to be patient with the publishing process should you wish to go that far. It may help to know that even those of us with books in the double and triple figures have to learn to wait.

Editors aren’t slow because they like to be mean. They’re slow because the process itself doesn’t encourage hustle. If they’re in the book business, they’re already working on lists that are two and three and four years into the future. Magazines and journals—probably three to six months ahead.

Editors are being forced to attend endless meetings, few of which have any immediate meaning for you and your work. They have their own host of complaining authors. Or they move to another publisher or magazine just when you were working on something together. Or they turn down everything you send them, almost always without comment.

Whatever the reasons for the interminable slowness, the snail-like nature of the business, it’s rarely just the author’s fault. All the editors I know read manuscripts on the subways, the trains, the ferries, the buses on their way to and from work. They take manuscripts with them on planes across the country and back again. They carry manuscript with them on vacations, to weddings, funerals, and family birthday parties. They read at night in bed, at conventions, and skip breakfast to read some more. And those are the manuscripts they have already bought! You can imagine how long it takes for them to get to the manuscripts in the piles of as-yet-unbought, even from top agents.

And then there’s the slush pile. Slush—or unsolicited manuscripts—are what’s sent out by new writers who have no agent, no contacts, no big name to drop into the letter of introduction.

But cultivating patience should never mean that you stop working. No rest between stories. And while those manuscripts are out making their rounds, getting occasional nudges from you, you are writing the next and even better piece.

I’m still learning how to write every single day.

RVC: What’s the best bit of writing advice you’ve ever received?

JY: Two things.

The first came early on in my career from an amazing editor name Francis Keene. I did about four or five books with her. She said to me: “You have great facility. Don’t be beguiled by it.” In other words, don’t just take the first thing that comes out. You’re good enough to go with the first thing that comes to mind and run with it. But just don’t leave it there.

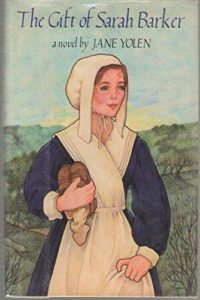

And the second one came from Linda Zuckerman, another amazing editor. I’d written a novel for her about the Shakers entitled The Gift of Sarah Barker. Set in the 1850s, everything that happened in this novel all happened in three days.

And the second one came from Linda Zuckerman, another amazing editor. I’d written a novel for her about the Shakers entitled The Gift of Sarah Barker. Set in the 1850s, everything that happened in this novel all happened in three days.

I first showed it to my husband who read it and said, “It’s too fast.”

Then I showed it to my agent who agreed—“Three days is too fast.”

Then when Linda bought the book, she asked, “Tell me why everything happens in three days?” She asked me the question instead of telling me I was wrong. And as I was trying to explain it to her, I realized that I had imposed a fairy-tale number on a historical story. It didn’t work.

Linda then told me: “Trust your reader.” And that became the second mantra after “Don’t be beguiled by your own writing.”

RVC: Tell me about SCBWI. You got involved early. What did it mean to you? What’s its relevance today?

I am now, outside of Steve Mooser and Lin Oliver who began SCBW (the “I” came in later—at the start, it was mostly just Writers, not Illustrators), the person who’s been in the organization the longest. The person who got there before me was Sue Alexander. It wasn’t even an organization when Sue joined, just Steve and Lin saying “Hey, let’s put on a show.” They were both young, working for the same company that had hired them to put out a series of textbooks for kids. They were good writers, but neither one had ever written for children.

They looked for an organization where they could join and learn, but there was no such thing. So they started one. They put an ad in the paper, and Sue Alexander, who lived in CA (where Steve and Lin worked), was the first one to sign up. Right after that, Sue came to Colorado for a workshop Uri Shulevitz and I were doing, and she quickly became a friend of mine.

She told me about this organization, I said “How do I sign up?” I had about 6 or 7 books out at that point, so I too wanted to be in an organization with other children’s book writers.

The “group” asked me to come to California where they were going to have their first-ever event—not a conference so much as a dinner. They needed dinner speakers, so they asked Sid Fleischman and me, as we were the only two well-published children’s book authors they knew.

While I was there, they were telling me that had plans to have an actual conference. I said, “I’ll come and speak at it. But I’m in the Northeast, can I make an SCBW outpost there and have people join?” They said that I could be the first regional advisor. They hadn’t even considered having regions for the group before.

So that’s what I did. First I spoke at their dinner and then I organized the New England Region of a barely-started SCBW.

RVC: What’s the value of SCBWI today for young writers?

JY: The value is that it’s still a place that’ll tell you everything that you need to know about getting started in the children’s book field. SCBWI’s board, which I’m a part of, is full of industry insiders—writers, illustrators, art directors, editors, agents, movers and shakers. We meet twice a year, once in NY and once in LA. And we’re a working board. We’re not just an in-name-only board. We discuss everything that has to do with children’s books and publishing—from this publisher is not paying its people, this bad boy of publishing has been abusing women, or this agent ran off with money to work with larger issues as well, such as how do we help get more minorities into publishing, a yearly list of publishers’ wants, what is trending, what are the addresses for those publishers, and how do people who don’t have agents get access, those sorts of things.

It’s very much the only organization that’s hands-on in terms of helping early-career writers. And it continues to serve the writers through their apprenticeships and well into the fullness of their careers.

RVC: Any final words of wisdom for those of us who, like you, are still learning to write every single day?

JY: Don’t believe anyone’s rules. Not even mine.

Write what you want, how you want, when you want. The only rule that counts is number one: Write the damn book.

Write it because you must. Because it whispers incessantly in your ear. Because it is your passion, your desire, your constant companion. Write it because you have to.

Write it because I want to read it.

RVC: Thanks so much, Jane!