This month’s picture book author is yet another journalist—we’ve got quite a surprising streak going here! Welcome to Kaitlyn Wells, an award-winning journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and The Washington Post, among others. Since she’s an expert on diverse literature, you can readily find her writing about that at The New York Times Book Review, BookPage, and Diverse Kids Books.

This month’s picture book author is yet another journalist—we’ve got quite a surprising streak going here! Welcome to Kaitlyn Wells, an award-winning journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and The Washington Post, among others. Since she’s an expert on diverse literature, you can readily find her writing about that at The New York Times Book Review, BookPage, and Diverse Kids Books.

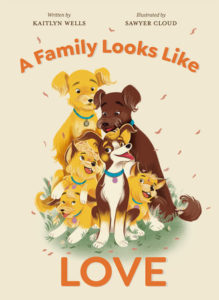

She’s not here for those things, impressive as they are. She’s here because her debut picture book, A Family Looks Like Love, arrives on May 31, 2022. We’ll talk about that in a moment for sure.

Kaitlyn lives in New York City with her “wonderful husband, rambunctious dog, and demanding cat.” She’s also active on social media, so let me share those links before getting to the interview. Lastly, she’s got a great newsletter for people who want to explore how Black, Indigenous, and womxn of color navigate the world.

RVC: In terms of your work as a journalist, you mention service journalism as an area of interest/focus. What does that mean to you?

KW: Being a service journalist is putting the reader first. I’m here to answer questions that people have about products or services. It’s teaching them how they can do things better or make their lives easier. That’s why I really like working in that type of medium–I get to help people better understand what’s going on in the world around them, and ultimately help them make better decisions for themselves and for their families.

RVC: Where did the interest in journalism come from?

KW: I’ve always been interested in journalism. I’ve always loved writing. I was that kid in grade school who was on the student newspaper, yearbook club, and all that. So, my trajectory was pretty normal. I got into nonprofit work for a little bit but I really wanted to get back into journalism as an adult. That’s why I pursued a graduate degree at Columbia University. I figured that was the right next step for someone like me who wanted to move to New York and try to make it in East Coast media.

RVC: How did it go for you there?

KW: Columbia was definitely not a cakewalk. It was a challenge. The curriculum was really rigorous. And I loved it. It was a fantastic learning experience. I made a lot of great connections, and it really helped me push my skill set further. I think that’s something that’s helped me be successful in my career. But I will admit grad school isn’t for everyone and it’s incredibly cost prohibitive. So, think it through carefully before you commit to a program.

RVC: What’s one of the most important things that you learned in that master’s program?

KW: Tough question. Probably the most important thing would be to believe in yourself. You’re surrounded by a lot of other people in your program who are just as talented as you, if not more so, and some of them have had access to more resources than you. And that’s okay. The competition can get quite fierce. So, it’s really important to trust yourself, do good work, and hopefully change the world for the better.

RVC: It’s impossible to look at your website without understanding that you have a profound interest in pets.

KW: I’ve always loved pets growing up. I’ve always had pets. I’ve been working with animal shelters since I was in high school. So, when a job opened up working at The New York Times’ Wirecutter as a pets writer, I jumped at the opportunity. They believed I had the right mix of experience and passion to do the job, so I’ve been working in service journalism at the intersection of technology and pets for the last several years. That led to the development of my first book that’s coming out as well.

RVC: We’ll talk about that book at length in just a moment. First, I’m curious about some of the talks you regularly give, such as the one on how to help writers emotionally connect with readers.

KW: It’s extremely valuable to learn how to get to the heart of what you want to say in your story, when you’re trying to make that emotional connection with the reader and with your character. Something I like to implement is called the heart mapping method, where you take a sheet of paper, draw a big heart in the center, and spend 15 to 30 minutes reflecting on what it was like growing up. I like to do this with every new manuscript–with it, I can really hone in on the theme of my story.

If you don’t know where to start, you can just do basic childhood memories.

- Who were you at your core?

- What was at the center of your heart?

- What did you value the most as a kid?

- What things did you like as a child?

- What experiences will you never forget?

- What happy or sad memories do you have?

But it’s more than that–it’s getting really specific, nailing down people, places, and memories, and then getting as detailed as you can. Once you have those details, those little nuggets of information can be threaded throughout your manuscript to breathe life into the characters that you’re trying to portray on the page. It can take a lot of work to do heart mapping the right way. Digging into your memories can be emotional. It can be draining or even traumatic for some people. But I think the more that you work at it, the better you get a sense of how you want a story to progress.

RVC: Is this something that you developed in or used in your journalist work? Or is it something that is particular to the world of kid literature?

KW: There are definitely some influences when it comes to journalism, particularly when you’re writing profiles, for example, because you want to be able to get across the people–or the places–that you’re writing about. It’s learning to use every descriptive tool in your toolkit. Some of that transfers into learning how to be a strong writer for kidlit as well, especially when you’re talking about emotions. Since journalism isn’t straight creative writing, I get to do more of that now with picture books.

RVC: You made a serious commitment toward the world of journalism and found a lot of success there. When did you decide to start to branch out into the role of kid literature?

KW: It wasn’t until a few years ago that I got serious about exploring kidlit. Like a lot of kidlit writers, I’ve always liked writing down ideas and telling stories to myself and others. But there came a time where I decided I’m still not seeing books out there that are really representative of the world that I live in. Or portraying people who look like me as well. So, I thought, Okay, I’ve got a story to tell. I would love to be able to tell it. Ultimately, I decided it’s time to commit. It really helped myself grow creatively in a way that traditional journalism hasn’t allowed me to yet.

RVC: I get the sense that A Family Looks Like Love comes from a place deep within you. What’s the story behind this story?

RVC: I get the sense that A Family Looks Like Love comes from a place deep within you. What’s the story behind this story?

KW: It’s a picture book about a dog who looks different from her doggy siblings. She looks different from the other animals in the neighborhood, too. These other animals tell her that they’re not really her family because they don’t match. She begins to internalize those feelings a lot and tries to change the way that she looks.

For me, that’s very personal because that’s some of what I went through growing up. My mom is white and my dad is Black, and I’m biracial. I spent most of my life surrounded by people who told me “That can’t possibly be your mom!” or “That’s not your dad! He’s nothing like you.” I’ve also been told by my extended family that I don’t belong just because of my skin color.

RVC: Wow.

KW: In processing those emotions, I found it was a tad easier to channel those experiences through the eyes of a dog. The inspiration for the book is my own dog, who actually doesn’t look like her real-life dog parents either. She’s a tricolor pup while her siblings in real life are blond, scruffy haired dogs. She’s also a dog that just loves everybody around her–she’s never met a stranger in her life.

It was easier for me to tell this story from the perspective of my dog going through a similar experience because as I said before, mining your heart, your emotional center, can be draining. It can bring up a lot of things that you don’t want to relive. So, that made it more accessible in my eyes. I think it also makes it more accessible for families who are still grappling with colorism or white supremacy, and they aren’t sure how to discuss race and might be turned off by the idea of reading it from a human perspective.

RVC: It strikes me that editing and revising a heart book like that is probably more challenging than with other books. One of the presentations you give is on self-editing, right? Did you have a hard time following your own advice?

KW: There were challenges editing this piece, especially when it came to revision before it went on submission because I wanted to tell the story in a respectful way. It was also one of the first manuscripts I worked on. So, there was definitely a huge learning curve for me. While in journalism you have to learn to write tight, clean sentences, it’s nothing compared to what you do in the kidlit community, especially for picture books because on average you only get 500 words to tell a story. And it still needs to be compelling and at the right reading level for a younger audience. That has its own set of challenges. It was great to work those muscles and figure out my stories from that perspective.

The biggest challenge with editing the book was that I had a particular way I wanted to portray certain characters. But when I got together with critique partners they would say, “Actually, I think it’d be better if you switch this character out for something else,” or “adjust that phrasing you have there,” or “I think it’s a little too harsh so let’s soften it up a bit for a younger audience.” That was a nice, albeit sometimes frustrating, learning experience for me.

RVC: What do you most appreciate or enjoy about Sawyer’s artwork?

KW: I love the joy that Sawyer brings to the story. Honestly, she did a beautiful job with the illustrations, and I’m eternally grateful. I was able to trust her with my vision, and she knocked it out of the park. There are a couple of pages in there that just really resonate with me. There’s one in particular where the main dog character, Sutton, feels really sad about herself, and she’s imagining what she would look like if she were to fit in better with her family. That just tugs on me every time I see it.

Sawyer did such a fantastic job matching the illustrations to the story and elevating it more than I could have on my own.

RVC: What was the most important lesson that you learned about picture books during the process from acceptance to almost publication?

KW:

The process is quite long. Gosh, I want to say from the time I got accepted to where I finally had my contract signed, it was at least six months. And, of course, this was during the height of the pandemic, so it was a little bit longer than what most people would expect.

Another surprising thing is that you have to be really proactive in this process to make sure all the trains are moving along, and that you’re getting the support that you need– through the editing process and leading up to publication. My book isn’t out yet, but I’m really excited to see what’s going to happen with it.

RVC: What was the most important contribution or change that happened as a result of the editorial feedback process from your publisher?

KW: Oh, that’s another tough question. There’s some dialogue between the main character and her dog family that was tweaked. Ultimately, I was able to help ensure that the main character, Sutton, takes ownership in the decisions she makes, rather than having the “adults” around her telling her what to do. I thought it was important for any young reader to see that there are decisions you can make that will ultimately be better, and you don’t always have to listen to others around you.

Prior to finding an editor and a publisher, I would say a big change that happened was the color of the dogs. In the original version, the family was mostly white to kind of mirror my own family on my mom’s side. As I got further along in the editing process, I realized that was centering whiteness more than I wanted it to. We were able to kind of revamp that a bit and change them to the yellow/blond coats instead.

RVC: As part of your process, it sounds as if you partnered with other people to promote each other and support each other. Do you want to talk a little bit about your group?

KW: I’m actually in several support groups. I think that’s something that every writer needs to get involved in. It’s amazing what you can do with like-minded people who all ultimately have the same goal.

RVC: But you’re specifically in a debut group, too. [Spoiler: Ryan’s in the same group, so he knows the answer to this one!]

KW: With you and a few dozen others, yes, I’m in PB22Peekaboo. With a debut group like this, you match up with anybody who has a book coming out in the same year as you and you basically act as a support network. You review each other’s titles, promo one another’s work on social media, work on panels together and speak at book fairs, and sometimes workshop new manuscripts, too. It really runs the gambit.

I really like the group that I’m in now.

RVC: So do I!

KW: I’ve been in a couple of other supportive groups that are more affinity oriented. Those are the ones that really helped me get my start in the kidlit community until I found my footing. I’m forever grateful for those as well.

RVC: Brag time. What do you have coming out next?

KW: I have something new happening in the world of kidlit. I can’t announce it yet but I’m really excited for what’s in the works. It’s going to be a STEM-oriented biography.

In the world of service journalism, I constantly have pieces running every week. You can always find that information here. I also have a newsletter that occasionally goes out that might have some of those updates.

RVC: What advice do you have for aspiring kidlit writers?

KW:

It’s important to remember–especially for anybody looking to break into kidlit–to always trust yourself. NEVER doubt yourself. I ran into this a lot on submission because my book was one of the #ownvoices stories. There were a lot of editors and publishers that my story didn’t resonate with. I took that personally, because it felt like I was putting something really vulnerable on the page, and people were telling me that there’s no place for it in the world.

I want everybody to know there is a place for your story. There is a place for representation–you just have to push through it and keep going. If anybody is actively trying to keep you out of this space, especially if they’re trying to stop or ban you, there are ways that you can combat that by reporting into national agencies, seeking news coverage on banned books, and of course, running for local office or for school boards to ensure literature is protected in our school systems.

RVC: Here’s the last question for this part of the interview. You’ve got a clear commitment to diversity. In fact, one of your presentations is on how to ensure diversity in journalism. How does that translate into the world of kidlit?

KW: It definitely starts with the industry itself, which means hiring more Black, Indigenous and people of color in the publishing industry, and actually buying books by BIPOC creators who feature stories about BIPOC characters as well, which isn’t always the case. If you look at the research, there tend to be less stories about us by us. So, that’s something that we have to really work on for telling our own stories from a diverse lens. I think it’s best to do it authentically and to tell stories that you know. And also read work by other people around you who have different experiences from your own so you can open your mind to something new. It can really help you creatively to get a better understanding of what works and what doesn’t, and see if there’s a place for the story that you want to tell on the shelves.

RVC: Thanks for that. But now it’s time for the SPEED ROUND. Silly fast answers followed by zoomy answers, please. Are you ready?

KW: Sure?

RVC: If you could only have one app on your phone, it would be…

KW: A calendar app.

RVC: If animals could talk which animal would have the most interesting things to say?

KW: Sharks.

RVC: What outdated slang do you use on a regular basis?

KW: Cool.

RVC: What animal do you think should be renamed?

KW: The platypus, but I don’t know what the new name should be.

RVC: Five things you can’t do your work without.

KW: Pen. Paper. Highlighter. A couple of reference texts that I like to use. And sunlight.

RVC: Some Kaitlyn wisdom in seven words or less.

KW: I’m not unique, but we’re ALL special.

RVC: Thanks so much, Kaitlyn! This was a real treat.