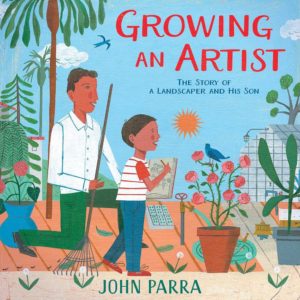

Growing an Artist: The Story of a Landscaper and His Son

Author: John Parra

Illustrator: John Parra

Simon & Schuster/Paula Wiseman Books

10 May 2022

40 pages

Ryan’s Review of the Writing

In Growing an Artist, author/illustrator John Parra shares the first time he finally got to go to work with his dad, a landscape contractor. After picking up Dad’s helper, Javier, the three headed to a house that had a wild yard. From his dad, John (“Juanito”) learned some of the tricks of the trade, such as shaping and trimming bushes, and mowing perfect lines.

This fun, proud moment for young John was darkened when he noticed a schoolmate (Alex) in a nearby house purposefully ignoring him. It didn’t make sense because at school, the two boys always talked. It’s not said in the text, but it’s easy for adults to infer that the boy was literally and metaphorically looking down on the yard workers–the art communicates that clearly. Yet John couldn’t quite figure that out at the time, though something about it really bothered him.

Already an artist, though, John noticed a nest of baby birds and sketched what he saw. But he still fretted about Alex ignoring him. As John ate Mami’s famous burrito (chorizo, avocado, and egg) while on a lunch break, he asked his dad if he’s proud of his job, almost as if voicing the disapproval Alex must feel.

Dad responded with: “You have to work hard and sometimes you are treated like you are invisible, but when you do something you love and get to be creative, you feel proud.” Dad might as well be talking about being an artist instead of being a landscape contractor.

The other stops in the day were rewarding and pleasant, and the people they met were the opposite of Alex–happy to see the team. Mr. and Mrs. Carroll in particular were quite excited. “Together [with John’s dad] they discuss how to transform the overgrown yard into a special place.” With his artist’s way of thinking, John realized, “I look around and start to see its potential too.” Later that night at home, John used his budding artistic skills to create his own landscape design, which his father loved and planned to use for the Carroll’s yard because the Carrolls loved it, too.

The conclusion of the book might as well serve as John’s artist manifesto: “I will use my art to tell the stories of hardworking, passionate people who make the world more beautiful.” The recurring memory of a disapproving Alex is lost to the passion of this final statement and his commitment to a life of creativity, beauty, and purpose.

An Author’s Note details how John’s father launched the landscape business after serving in the United States Army, and how John worked alongside him for twelve years before taking illustration and fine art classes in college and embarking on a career as an artist.

There’s a lot of room for discussion here beyond the scope of what many picture books offer. Being proud of your parents and what they do for a living. Not making snap judgments or being overly worried about what your peers think. How encouragement can grow a passion into one’s life’s work.

Ultimately, Growing an Artist is an intriguing book that would be a nice addition to libraries and private collections.

4 out of 5 pencils

Loreen’s Review of the Illustrations

Blueprints of a landscaping design serve as endpapers for Growing an Artist, foreshadowing a big project to come. Young John narrates the action when he accompanies his father on the job for the first time. The crisp, hand-painted illustrations have plenty of details for readers to enjoy, including a variety of plants, animals, and people as well as the tools and machines of the trade.

After picking up Javier, the three drive to several houses to mow, trim, and spruce up the yards. They buy a special rose at the nursery and drop off the yard waste at the city dump to be recycled into mulch. John draws several pictures in his sketchbook along the way. When a new plan is needed for a couple’s overgrown yard, he assists in creating the new design as well as helping to put the plants into the ground.

Every 2‑page spread depicts one scene (with one exception where a left and right page show different scenes.) This allows for expansive views of the nursery, the city, and the yards where the work takes place. The well-chosen color scheme enhances the lively paintings.

One critique is that the text is long winded at times, including unnecessary information that slows down the narrative and sometimes does not sound like a child narrator (e.g. “Papa demonstrates how to shape and trim bushes.”) Some particulars could have been shown in the illustrations or just left out. For example, the sentence about the “registration booth” at the dump is not needed.

In the end, the charming sketches by the young boy revisit the various events and support his conclusion that making the world a more beautiful place is important work worth celebrating.

4 out of 5 crayons

Loreen Leedy is the author-illustrator of more than 40 popular picture books that have received many rave reviews and honors. Her titles such as Measuring Penny, Amazing Plant Powers, and Crazy Like a Fox: A Simile Story often include math, science, and language arts content. Her most recent book, Step by Step, features footprints made by baby animals including a puppy, duckling, and fawn in a page-turning question and answer format. It makes an appealing nonfiction choice for preschool, kindergarten, and first grade age levels.

To see Loreen’s work and download free book activity printables, please visit www.LoreenLeedy.com.

Edna Cabcabin Moran is an author/illustrator, multi-disciplined artist, educator, and advocate for youth voices and diversity in publishing. She is also a dancer with acclaimed hālau hula and dance company,

Edna Cabcabin Moran is an author/illustrator, multi-disciplined artist, educator, and advocate for youth voices and diversity in publishing. She is also a dancer with acclaimed hālau hula and dance company,

Every night at home, as part of their bedtime routine, the mother paints vivid pictures of her memories for her son. “She and her friends would walk to the river and play there all day. They caught fish, unearthed treasures beneath rocks, splashed each other, and dried themselves on the pebbled riverbank.” As a boy, I dreamed about where my family members grew up, and even today, I still do this with my friends living abroad, creating colorful images in my mind. When a story tugs at your memories, you know you’re in for a treat.

Every night at home, as part of their bedtime routine, the mother paints vivid pictures of her memories for her son. “She and her friends would walk to the river and play there all day. They caught fish, unearthed treasures beneath rocks, splashed each other, and dried themselves on the pebbled riverbank.” As a boy, I dreamed about where my family members grew up, and even today, I still do this with my friends living abroad, creating colorful images in my mind. When a story tugs at your memories, you know you’re in for a treat. Joshua Walls is a children’s author and travel writer who isn’t afraid to fuse, challenge, or deconstruct genres in the pursuit of creating compelling stories. Currently, he lives in Sarasota,

Joshua Walls is a children’s author and travel writer who isn’t afraid to fuse, challenge, or deconstruct genres in the pursuit of creating compelling stories. Currently, he lives in Sarasota,

Kelly Light lives in Amherst,

Kelly Light lives in Amherst,